Why is Amazon building bookstores?

Loading...

In a world that seems inexorably inclined toward the digital universe, the online giant Amazon appears to be bucking the trend.

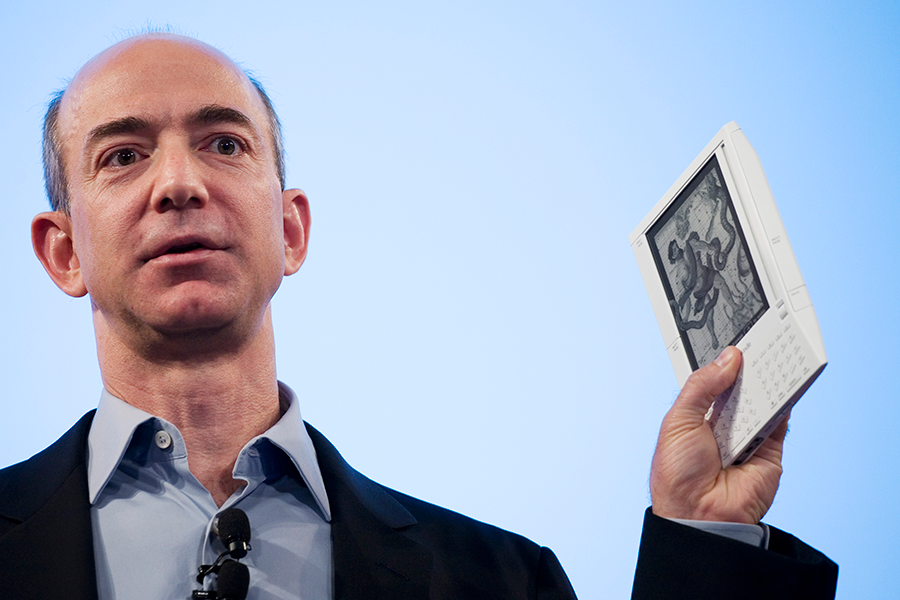

Having already opened its first bricks-and-mortar bookstore last year in Seattle, Amazon's chief executive Jeff Bezos confirmed Wednesday that it plans to open more, with a second already under construction in San Diego.

Is Amazon an outlier, or does this herald something of a reversal in accepted wisdom on the future of physical stores?

"Amazon spent the first 10 to 20 years convincing people to buy online," Marlene Morris Towns, a professor of marketing at Georgetown University's McDonough School of Business, tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

"Now there is a shift, with lots of online sellers moving into physical spaces."

While Dr. Towns thinks it unlikely that retailers who have shifted to a heavier online presence will move back, she does see Amazon's move as reflective of a wider trend, whereby purely online stores are seeking to grow their physical presence.

"We're definitely going to open additional stores, but how many we don't know yet," Mr. Bezos said at the annual shareholders meeting, according to the BBC. "In these early days it's all about learning, rather than trying to earn a lot of revenue."

A company spokeswoman confirms via email that Amazon has "one location at University Village in Seattle, WA and will open a second location at UTC Mall in San Diego CA later this year," but declined to comment on the underlying strategy.

There has been much speculation on what lies behind Amazon's initial foray into traditional retail space, and whether it could be the harbinger of something bigger.

"You've got Amazon opening brick-and-mortar bookstores and their goal is to open, as I understand, 300 to 400," Sandeep Mathrani, the chief executive of mall operator General Growth Properties Inc., told reporters in February, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Though Mr. Mathrani later "backed away" from the statement, the very fact that Amazon has stepped into this arena at all – coupled with Bezos's vague statement on numbers – could be enough to send shudders down the spines of traditional booksellers, already stumbling under the onslaught of online competition.

Indeed, Professor Towns admits there is something sadly ironic about the situation: Amazon is now moving into the very space it forced some sellers to abandon, having in no small part contributed to the decline of companies like Barnes and Noble.

Like other online retailers, Amazon is realizing that there is something special about that physical space, characteristics that the online experience can never quite replicate. And while the stores themselves may make little profit, the indirect benefits could be substantial.

"When you walk into a store, surrounded by everything the retailer represents – the staff, the layout, the products, the music – you get a sense of what this brand really is," says Towns. "Despite the convenience and lower prices of online shopping, consumers still miss out on the 3D experience."