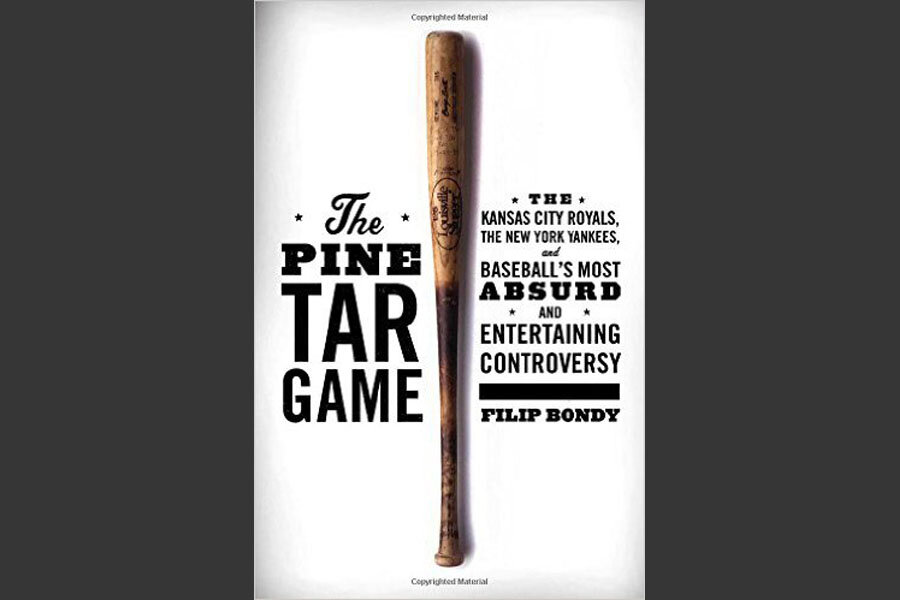

Long before pro football’s Deflategate controversy over the inflation level of game balls, baseball had an equally mole hill-turned-mountain brouhaha. It involved one of the game’s best hitters, Kansas City’s George Brett, whose two-runner homer in the top of the ninth put the visiting Royals ahead in a late-season 1983 game against the Yankees in Yankee Stadium. But the home plate umpire was approached by New York manager Billy Martin about an obscure rule regarding the amount of pine tar on a player’s bat. A quick measurement revealed Brett exceeded the limit, so he was called out for an “illegally batted ball,” which caused the Royals star to go ballistic with rage. Author Filip Bondy witnessed it all as a young sports writer, and now uses this bizarre episode to examine the larger narrative of shifting values in baseball and to rewind the rivalry between the mighty pinstripers and the small-town Royals.

Here’s an excerpt from The Pine Tar Game:

“Umpires had warned him, and there was no hiding the fact that [George] Brett was a complete pine tar mess, Exhibit A in a baseball court of law. Most batters have certain habits they rely on when they step to the plate. Sometimes these are superstitious rituals, sometimes they are muscle memory cues. Brett routinely massaged the barrel of his bat before placing his left foot first in the batter’s box. The pine tar would get all over his left hand and then he often would tip his batting helmet with that hand and the helmet would get all gummed up from the pine tar. That stuff was everywhere, all over Brett, a launderer’s nightmare. So there may have been some cold-blooded calculation involved in the unlawful use of this bat, even if the crime was ultimately petty. And while Brett might have known he was guilty of stretching the rules in this matter, he seemed largely unaware of the potential consequences for such misconduct.”