'Stonewall' is a problematic collection of stereotypes

Loading...

Best known for such spectacle-driven blockbusters as "2012" and "The Day After Tomorrow," Roland Emmerich has made his reputation exploiting audience's anxieties over what the future may hold: What if a second ice age struck or a series of tidal waves wiped out most of mankind? With "Stonewall," the openly gay director puts such speculative fantasy aside and opts to engage with a more intimate real-world crisis, using the sheer dynamism of 1969's historic Greenwich Village uprising as a platform to address the epidemic of homelessness among LGBTQ youth, past, and present. While it's encouraging to see such a subject treated with the same grandiosity afforded alien invasions, particularly at a moment when gay rights hold such currency, representation-starved audiences deserve more than this problematic collection of stereotypes, which lacks the galvanizing power of such recent we-shall-overcome triumphs as "Selma" or "Milk," and won't draw anywhere near their numbers.

This isn't the first time Emmerich has stepped away from mega-budget studio pictures to tackle more personal material, though critics came with their knives pre-sharpened for 2011's "Anonymous." With "Stonewall," skeptics actually swooped in to preemptively scold the film for "white-washing" the Christopher St. riots after an early trailer revealed how Jon Robin Baitz's screenplay invents a straight-acting caucasian hero (played by "War Horse"'s lily-white Jeremy Irvine) to throw the first brick, potentially marginalizing the diverse trans activists who led the uprising.

But let's be fair: "Stonewall" is no disaster, and to all those waiting to tear it apart, perhaps the best that can be said is that Emmerich's film is neither as bad nor as insensitive as predicted, though its politics certainly are problematic – especially as regards its lead character, whose concerns are so far removed from everyone else in the ensemble. After briefly teasing the riots, the story flashes back three months to small-town Indiana, where Irvine's all-American Danny Winters runs afoul of his football coach father (David Cubitt) after some of his teammates catch him fooling around with the high-school quarterback (Karl Glusman). Coming home to find his bags packed, Danny leaves for New York City, where the Columbia-bound scholarship student had been headed all along.

Baitz's emotional-wallop stageplays may have twice put him in the Pulitzer Prize finalists' circle (for "A Fair Country" and "Other Desert Cities"), but here, he's none too subtle about what the West Village's Sheridan Square means to Danny, who stumbles around the downsized (but otherwise accurate) intersection looking as dazed as Dorothy did upon her arrival to Oz, stunned by all the "alternative" lifestyles on display: There are boys in girls' clothes, men openly flirting with men. Danny meets Ray, AKA Ramona (Jonny Beauchamp), a flamboyantly effeminate Puerto Rican with long hair and handmade ladies' costumes.

Danny may be the audience's uneasy proxy in this wild, full-color picture, but Ray serves as both its heart and soul – a charismatic ambassador for the travails and triumphs the multi-culti trans community faced at the time. While it was Emmerich's agenda to address America's LGBTQ homeless problem via the Stonewall situation, Baitz responds with the inspired notion of treating the story as a dysfunctional family drama – where "family" refers less to the biological bigots who reject their own nonconformist kid than to the scrappy replacement community that forms around the runaways, outcasts, and hustlers who came together on Christopher St. that fateful summer.

With his white T-shirt and 1950s hairstyle, Danny sticks out like a sore thumb among Ray and his friends, marveling at their displays of civil disobedience. Though seldom explicit, the movie hardly attempts to sanitize the sexual activity of the era.

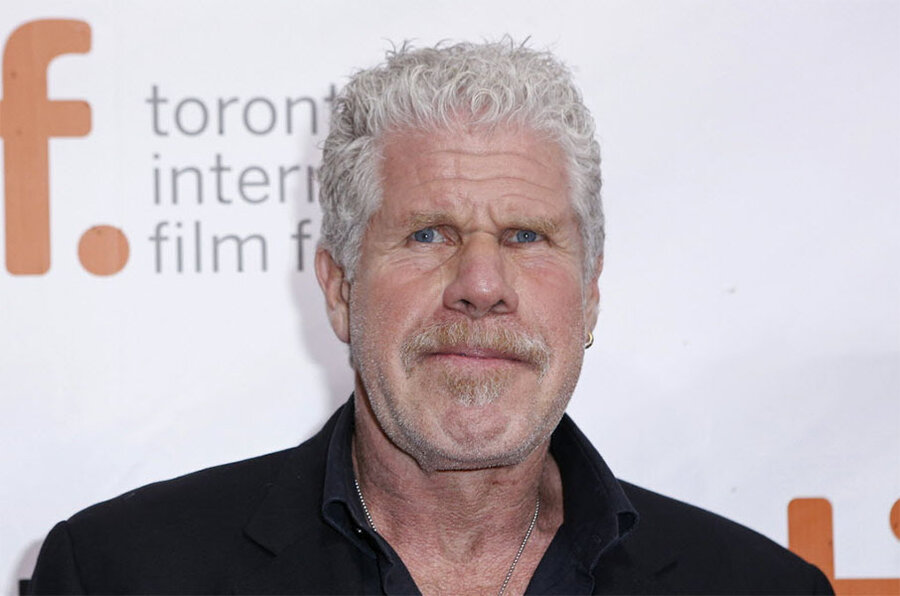

Ray clearly has a soft spot for Danny, as does a local activist named Trevor Nichols. After picking Danny up one night at the Stonewall Inn, Trevor brings the kid to meetings and offers him a place to crash directly opposite the bar. Ray's favorite dive, Stonewall is a dingy hole in the wall whose Mob managers (namely Ed Murphy, played by a bald-headed Ron Perlman) are bold enough to break the law and serve alcohol to gays – though it comes at the price of regular police raids, wherein the crooked cops of New York's Sixth Precinct routinely collect kickbacks, while taking people into custody.

For a certain generation of moviegoer – say, those still below drinking age – they may never see a place like Stonewall in their lives, as big cities now offer theme park-worthy mega-clubs, while smaller ones lose their gay bars as virtual cruising apps siphon away the need for shared social spaces. But in 1969, at a time when the "gay community" didn't exist as anything so unified, Stonewall provided a place to meet and connect with others of a persecuted underground community. "Stonewall" captures that vibe, amplifying the emotions – and dangers – that a neophyte might feel if confronted by such temptations for the first time, then burying much of it in flashy period clothing and tunes (the Stonewall jukebox serves up "Venus" and "A Whiter Shade of Pale," among others).

Attempting to do right by history, Emmerich and Baitz have complicated an event that now stands as the catalyst for the gay pride movement, going out of their way to establish why the cops chose to raid the Stonewall Inn on June 28, and why the lesbians and female-attired trans clientele finally decided to rebel against the harassment they'd been getting from all sides.

It's a curious choice to get so intricately contextual when Emmerich merely intends for Stonewall to serve as backdrop to Danny's coming-out arc, especially since it makes the subsequent riots seem like one great big misunderstanding: Like Danny, Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine (Matt Craven) looks like a fossil of the 1950s, and the film wants us to believe that he was acting out of concern for the LGBTQ community when his Public Morals squad raided Stonewall. Clearly, it was the straw that broke the camel's back, and the movie finally flares to life once Danny – a cheap poster boy for the cause among so many compelling trans people of color (and of whose life stories would have been deserving of lead status) – tosses that brick and ignites the fight.

Some will inevitably complain that the cast leans too heavily on cisgender actors (those who identify with their birth gender in real life), considering how seldom trans thesps are cast in any kind of role.

With the exception of Beauchamp's breakout performance as Ray – a luminous, can't-look-away contribution deserving of the character's name – the movie would benefit from better acting all around, as Emmerich stages so many wooden character scenes en route to the explosive riots. And yet, he doesn't seem to have distilled the most powerful lesson of his disaster-movie career: Audiences want to see The Wave. "Stonewall" cuts that short, and by condensing days of protest into a single night, deprives them of both the full spectacle and subsequent impact of events that changed LGBTQ history forever.