Through an African lens, ‘a story for the world’

Loading...

| Johannesburg

One of the first African photographers for Time and Life magazines, Priya Ramrakha captured Africa’s headlong plunge into the independence era with the nuance of an insider and made a name for himself photographing the continent’s conflicts. But his photos also captured life at its most ordinary: a traffic jam of bicycles in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; a troupe of off-duty circus animals clomping down the streets of New York.

For decades his career remained largely unknown. But a relative found what he was looking for in the basement of Ramrakha’s brother: thousands of negatives, brittle newsprint, and other relics of a prolific career. Those fragments led to more found photos and a documentary, exhibition, and book.

Art historian Erin Haney says she was struck by how strongly many young activists connect with Ramrakha’s photographs of social movements across Africa. “What’s happening now is the aftermath of that era, so it does matter to people,” Ms. Haney says. “Priya’s story is a story for the world.”

Why We Wrote This

Kenyan photojournalist Priya Ramrakha’s life ended in 1968 while he was covering a civil war, and thousands of his images were thought lost. A new book documents Africa’s independence era in his pictures.

As independence movements mushroomed across Africa in the 1950s and ’60s, Western reporters flocked to the continent, eager to capture a place on the precipice of history. Many came to see what one American news program on Congo called Africa’s “primitive politics and tribal warfare.” But Kenyan photographer Priya Ramrakha (1935-1968) had a different lens on Africa, quite literally.

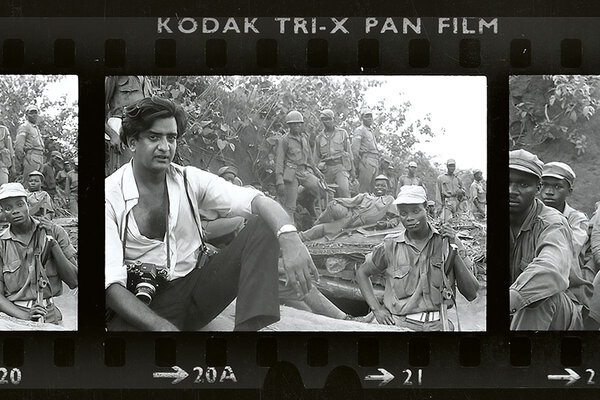

One of the first African photographers to be contracted by Time and Life magazines, he captured Africa’s headlong plunge into the independence era with the nuance of an insider and made a name for himself photographing the continent’s conflicts. During a stint studying in the United States, he photographed American civil rights luminaries like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. as well as the foot soldiers of an American civil rights movement that, in many ways, mirrored the struggles on his home continent. But his photos also captured life at its most ordinary: a traffic jam of bicycles in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; a troupe of off-duty circus animals clomping down the streets of Manhattan. “He was seldom at a distance. He liked to be where the action was,” wrote Ramrakha’s friend, the writer Paul Theroux, in the introduction of a recently published photo book on the photographer. “In many shots it’s clear that he had won acceptance, and was unthreatening enough to be allowed to get close to his subjects.”

And then he was gone. While covering a civil war in Biafra, Ramrakha was hit in the back by a stray bullet. For decades, his career remained largely unknown, with many assuming his archive was lost. But in the early 2000s, Shravan Vidyarthi, the son of one of Ramrakha’s cousins, found what he was looking for in the basement of Ramrakha’s brother: thousands of negatives, brittle newsprint, and other relics of a prolific career.

Why We Wrote This

Kenyan photojournalist Priya Ramrakha’s life ended in 1968 while he was covering a civil war, and thousands of his images were thought lost. A new book documents Africa’s independence era in his pictures.

Those fragments of Ramrakha’s career became the basis for a documentary, “African Lens: The Story of Priya Ramrakha,” which was released in 2007. And then, Mr. Vidyarthi says, things began to snowball. “More people started coming forward with photographs – old girlfriends, other relatives,” he says. What should he do with them? In 2017, he and American art historian Erin Haney curated an exhibition of Ramrakha’s photos at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa.

The exhibit took place while student protests gripped the university. Ms. Haney said she was struck by how strongly many of the young activists connected with Ramrakha’s photographs of social movements across the continent. “It made us realize kids are still missing their own archive, their own history,” she says. “So we began to think how we could get this work into educational settings, to be used more widely.” They realized there was no way they could fund the project on their own, and few publishers would foot the bill for glossy coffee-table photo books. So they turned to Kickstarter.

Within five weeks they had raised over $40,000 to help with the costs of design, scanning photographs, and printing. And in March the finished copies of “Priya Ramrakha: The Recovered Archive,” featuring the photographer’s own shots mingled with family photos, documents, and essays (including the one by Mr. Theroux), began arriving on doorsteps from Nairobi to New York.

But for both Ms. Haney and Mr. Vidyarthi, the completion of the book felt more like a beginning than an ending. Having seen the response of students in Johannesburg and elsewhere, they say, they are eager to get Ramrakha’s photos into school curricula and to put his photos of the era of African independence in front of new and bigger audiences on the continent and elsewhere. “What’s happening now is the aftermath of that era, so it does matter to people,” Ms. Haney says. “Priya’s story is a story for the world.”