The UN declares an International Women's Day theme each year. This year’s focus? “A promise is a promise: Time for action to end violence against women.”

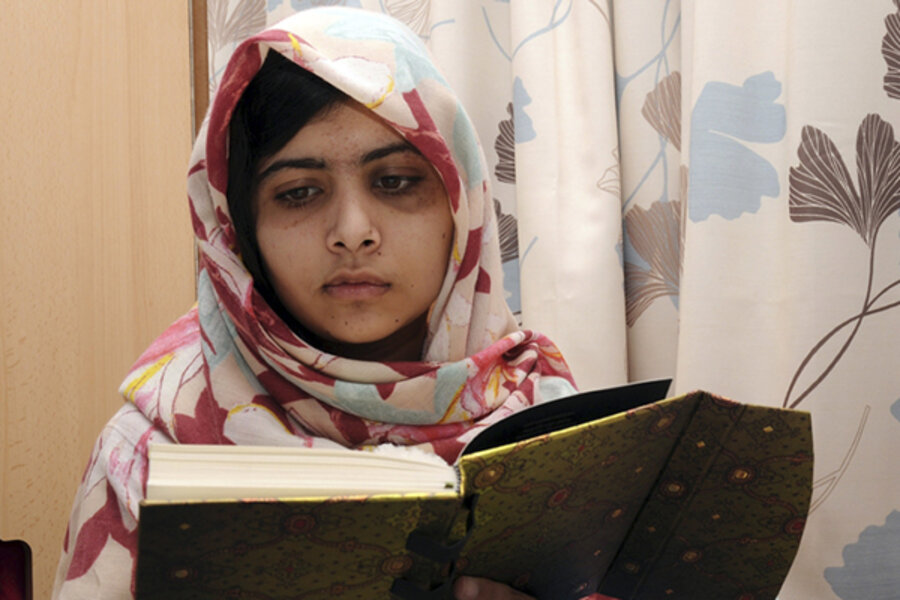

The story of Malala Yousufzai, the schoolgirl shot in the head by the Pakistani Taliban for advocating education for girls, reminded the world that the promise of girls’ education and safety in rural Pakistan - among other places - has not been met.

The Monitor’s Ben Quinn wrote that when Malala was transferred to a hospital in Britain for treatment, for some of the diaspora in the UK, the attack “struck a chord in parts of society where traditional attitudes, in particular those carried over from rural northern Pakistan, still manifest themselves through resistance – in a minority of families – toward education of girls.”

Not long after the world caught its breath from the Malala incident, gruesome news from India energized the international dialogue on violence against women:

The case of a young woman brutally gang raped on a bus and left for dead in New Delhi, brought the issue to the forefront in a way that may yet be a game changer for India and other countries.

In India, thousands of people protested and pressured the police and government to speed up the sluggish judicial system process in cases for rape, known to drag on for years. It also may have helped spur a movement in Indonesia – though still small – to take to the streets to protest offensive remarks from an Indonesian high court judge who “joked” that women might enjoy rape.

Much has been made in the past couple of years of the important role women can play in revolution. But there has been a dark side of that participation: In Egypt, women who dare to go out to protest the government, as the Monitor’s Kristen Chick reports, have faced profound threats to their safety:

Tahrir square has become a terrifying place for women as sexual assault becomes more common and violent. But fed up, civilians are making it their job to prevent it and rescue women from attacks.

Several groups have formed, organizing to prevent such attacks, rescue women who are attacked, and raise awareness about an issue that is not often openly addressed.

And encouragingly, hundreds of volunteers created an organized effort to respond to the escalation of assaults against women in Tahrir.

As women battle such violence across the world, what motivates change?

In Latin America, a region where emerging economies are increasingly paying attention to GDP output, Sara Miller Llana looks at whether a first-of-its-kind study that quantifies the intergenerational price tag of domestic violence could motivate policy-makers, where other efforts have failed.