Russia’s top mercenary leader turns on Kremlin. What’s behind rift?

Loading...

| Moscow

Yevgeny Prigozhin’s private army, the Wagner Group, has borne the brunt of the incredibly costly battle that has raged since last summer amid the ruins of Bakhmut.

And over the past 10 days, the Kremlin-connected entrepreneur has publicly threatened to pull his forces out of Bakhmut, appearing in a video with a field of dead Wagner troops he claimed were victims of Defense Ministry negligence. “Soldiers should not die because of the absolute stupidity of their leadership,” he said.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWagner mercenary leader Yevgeny Prigozhin has been engaged in very public criticism of Russia’s war effort. Experts say that it’s not a challenge to Vladimir Putin, but positioning for the post-war order.

This extraordinary spectacle has led to speculation about an imminent collapse of Russian lines around Bakhmut, or even a political challenge to the Kremlin by Mr. Prigozhin.

Russian experts say there is indeed a struggle for influence and resources between Mr. Prigozhin and the Russian military bureaucracy. But they say he is not so much challenging the powers that be in Moscow, as he is trying to outmaneuver rivals for the Russia that emerges from the war.

“Prigozhin’s popularity may be a threat to the military bureaucracy, but not to Putin,” says Sergei Markov, a former Kremlin adviser. “Prigozhin doesn’t want to be president. He wants to build his brand, to become the most powerful private army in the world. He wants to have projects in many countries and become very rich.”

Russia’s most successful military leader in the Ukraine war so far is not a soldier at all.

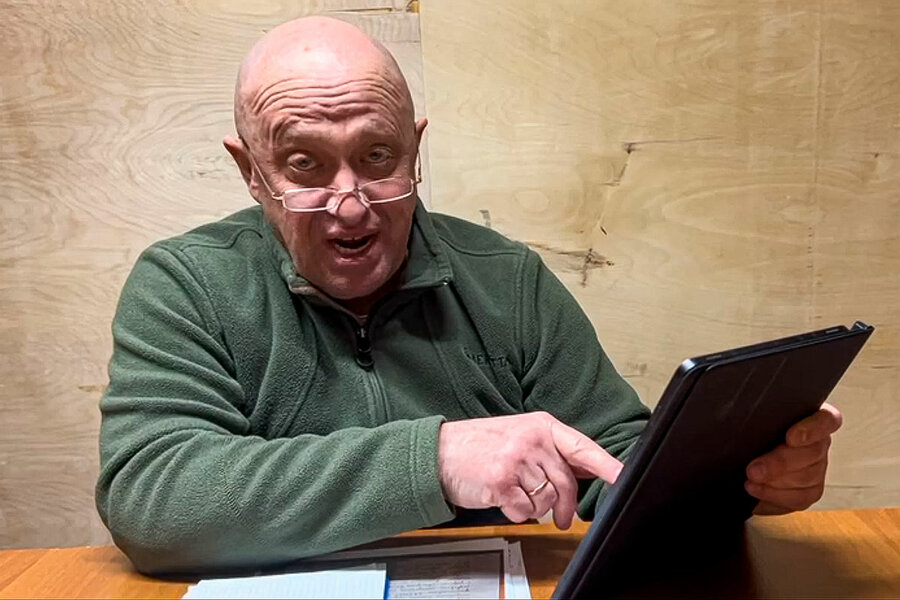

Yevgeny Prigozhin is a former convict and Kremlin-connected entrepreneur whose private army, the Wagner Group, has borne the brunt of the long, grinding, and incredibly costly battle that has raged since last summer amid the ruins of Bakhmut, once a quiet Donbas mining town.

And over the past 10 days, he has publicly threatened to pull his forces out of Bakhmut, appearing in a video with a field of dead Wagner troops he claimed were victims of Defense Ministry negligence. A week ago he accused Russian troops of “fleeing” the battlefield near Bakhmut, leaving his men exposed. “Soldiers should not die because of the absolute stupidity of their leadership,” he said.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWagner mercenary leader Yevgeny Prigozhin has been engaged in very public criticism of Russia’s war effort. Experts say that it’s not a challenge to Vladimir Putin, but positioning for the post-war order.

This extraordinary spectacle has led to speculation about a rift in Moscow’s upper echelons of power, an imminent collapse of Russian lines around Bakhmut, or perhaps even a political challenge to the Kremlin by Mr. Prigozhin and the right-wing nationalist hawks who revere him.

Russian experts say there is indeed a struggle for influence and resources between Mr. Prigozhin and the Russian military bureaucracy, which clearly hates the private contractor. But they say he is not so much challenging the powers that be in Moscow, as he is jockeying for his own post-war position in what is anything but a monolithic Putin-era Russian establishment.

“Prigozhin is trying to act like a politician, and Putin may not be ready to tolerate too much independence,” says Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center who continues living and working in Moscow. “But this is a strong authoritarian state which is ready to use all sorts of people to achieve goals that look very strange for the 21st century. For Putin, right now, it’s extremely important to fight and win this war. He needs men who can get things done, and that’s why he tolerates Prigozhin.”

A construct of Mr. Putin’s system?

Mr. Prigozhin, who served a decade in prison for robbery and fraud in the 1980s, began with small-scale businesses in post-Soviet St. Petersburg, mainly in the food catering field. After Russian President Vladimir Putin came to power, Russia’s wealthy elites had a choice between accepting political obedience or leaving the country, and Mr. Prigozhin, by then a successful grocer and restaurateur, chose the former.

Mr. Prigozhin became close enough to the Kremlin that he earned the sobriquet “Putin’s chef.” He grew wealthy on official catering contracts and began to branch out. Among other things, he started the Internet Research Agency, a cyber-trolling outfit that became notorious in the United States for allegedly interfering in the 2016 elections.

Although Mr. Prigozhin publicly denied it until last September, he’s best known for founding the Wagner Group, a private military contractor he says was modeled on U.S. examples like Blackwater, in 2014. The group was reportedly named for the call sign of its first commander, Dmitry Utkin, and its goal was to assist Ukrainian separatists in the Donbas without leaving official Russian fingerprints. The Wagners extended operations to Syria and several countries in Africa, where they were able to support Russian foreign policy goals in various ways, yet enable Moscow to maintain official deniability. Estimates of the size of the Wagner forces vary, but they generally seem to be somewhere in the tens of thousands of troops.

Andrei Soldatov, a specialist in Russian secret services who is now with the Center for European Policy Analysis, argues in a recent piece for Foreign Affairs that, far from being a wild card or a threat to Russia’s power structure, Mr. Prigozhin’s entry into private military operations was probably sponsored by Russian military intelligence, the GRU, and is very much in line with the traditional Kremlin style of creating different forces to pursue various goals and to play against each other.

“The GRU was instrumental in the emergence of the Wagner group, and the agency established a special department to supervise it,” says Mr. Soldatov. “Lately it looks as though Prigozhin is desperate to preserve the reputation of Wagner as the only force that’s capable of going on the offensive,” hence his strange public antics. “But this doesn’t necessarily mean that he’s a loose cannon” or a threat to the Kremlin, he adds.

Many argue that Mr. Prigozhin and his private army are ultimately a construct of the system created by Mr. Putin and that he serves at the pleasure of the Kremlin.

“The Wagners are an outsourcing model, who are able to do things that the state might not be able to openly carry out, such as recruiting prisoners straight out of jail and sending them into battle,” says Mr. Kolesnikov, the Carnegie expert. But “Yevgeny Prigozhin is simply a state hireling.”

“He wants to build his brand”

After Russia invaded Ukraine last year, the Wagner role grew immensely. Already involved in the Donbas conflict for several years, the group honed its skills at assaulting heavily defended Ukrainian positions, especially around Bakhmut. Mr. Prigozhin made the rounds of Russian prisons last September, offering freedom for any convict who would volunteer and serve six months on the Ukrainian front. It’s not known how many signed up, but Mr. Prigozhin recently noted that about 5,000 men have completed that service and returned to normal life.

Unlike the Defense Ministry, he has also been fairly honest about the casualties his men have suffered in the grueling attritional fighting around Bakhmut, putting losses at about 90 soldiers per day – which, he insisted, was far less than Ukrainian casualties. The ministry may also envy his relative success as the leader of the only Russian force that has consistently moved forward, however slowly and painfully, over the past several months.

In fact, Mr. Prigozhin has been in a constant squabble with the Russian military brass. He has cited them for allegedly failing to supply his Wagner stormtroopers with enough ammunition to blast through the rows of high-rise buildings in western Bakhmut, where Ukrainian troops still hold on. He has also accused the regular Russian troops who are meant to be securing the Wagners’ flanks of poor performance.

Not being a professional soldier – or even part of the chain of command – enables Mr. Prigozhin to take his complaints directly to the public via social media and sympathetic Russian journalists. Though he gets very little coverage in mainstream Russian media, everyone knows his name, and polls suggest that Wagner forces are more popular than the official Russian army. Hence, Mr. Prigozhin’s social media appeals get enormous traction.

Major public opinion agencies, like mainstream Russian media, have conspicuously avoided polling the public about Mr. Prigozhin and the Wagners. But one less formal survey carried out by the “Myusli Lavrov” Telegram channel found that 80% of its respondents would sooner sign a contract with Wagner than with the official Russian army. And at least one Russian military unit has posted a video appeal asking to be transferred to the Wagners.

“Prigozhin is something like a Russian version of Elon Musk, and his relationship with the Defense Ministry is like that of a huge, successful corporation struggling with government bureaucracy,” says Sergei Markov, a former Kremlin adviser. “Private corporations can be very effective, though perhaps it’s dangerous to give them too much power. But Prigozhin has been moving forward, street by street, in Bakhmut because he’s an effective leader, he has an excellent team whom he pays very well, he’s innovative. He rewards success and punishes failure. ...

“The Russian army’s problems are mainly the burden of bureaucracy. Communications on the battlefield take hours for them, whereas the Wagners do it in minutes,” he says.

Mr. Markov argues that Western analysts are mistaken to view Mr. Prigozhin as a potential political challenger to the Kremlin.

“Prigozhin’s popularity may be a threat to the military bureaucracy, but not to Putin,” he says. “Prigozhin doesn’t want to be president. He wants to build his brand, to become the most powerful private army in the world. He wants to have projects in many countries and become very rich. Right now, he needs to win in Bakhmut.”