In Kashmir, the paintbrush becomes an alternative tool for protest

Loading...

| Srinagar, Indian-controlled Kashmir

Masood Hussain fondly remembers the 1970s and '80s in his native Kashmir – a place that was peaceful and verdant, where the now 63-year-old artist could interact with visiting artists from around the world and paint landscapes.

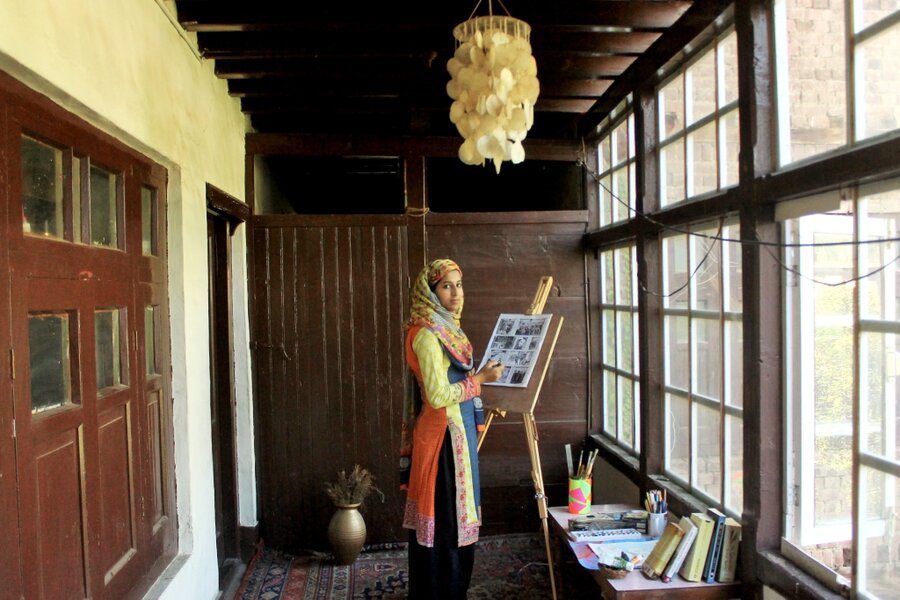

For Khytul Abyad, such an artist’s paradise seems an elusive dream. Born in 1993, the 23-year-old artist watched as Kashmir’s beauty was overshadowed by political crackdowns, torture, Army bunkers on every street, and long waits in traffic as Army convoys passed by. For her, growing up in Kashmir mainly meant negotiating the ongoing conflict between Kashmiris opposed to India’s occupation of their land.

Mr. Hussain and Ms. Abyad are working to document the conflict they have seen explode around them this summer, as tensions over India’s occupation of Kashmir soared after the killing of the popular militant rebel leader Burhan Muzaffar Wani.

For both of them, Kashmir’s brutal history has become the canvas, their art their channel of dissent, protest, frustration, and hope. And they see others choosing the same path.

“In [the] 2008, 2010, and 2016 uprising, we've been seeing new artists emerging, either as musicians, rappers, poets, or painters,” says Abyad.

“Being in a curfew for months, not being able to go out of home … this is the perfect time for art to emerge because there's so much going on inside and the frustration becomes internal, rather than external,” she adds.

Kashmir has been a contested area of South Asia since the partition of British India in 1947. The region is claimed by both India and Pakistan; the Indian-controlled part has periodically been convulsed by protests.

This summer saw some of the worst conflict since 2010. Massive numbers have turned out in public demonstrations against often oppressive Indian rule and endorsement of a new age of militancy. Some 85 civilians have been killed, and at least 11,000 injured, hundreds of them by pellet guns, weapons that have become controversial symbols of this summer’s turmoil for the serious eye injuries they have inflicted.

Schools and commercial establishments have been periodically closed under curfews, and the internet cut off in an effort to prevent protests. Thousands of protesters have also been arrested in the ongoing crackdown, including Abyad’s older brother, who was detained on July 8 and continues to be held in a police station.

Two views

Abyad and Hussain’s perspectives are shaped by their very different experiences: While Hussain knew Kashmir before the armed rebellion started in 1988, Abyad was just 18 months old when unknown gunmen assassinated her father, Mirwaiz Qazi Nissar, a popular pro-freedom leader and a Muslim cleric. As she grew older, words like azaadi (Freedom) and tehreek (movement) became familiar rallying cries.

It was during the 2008 unrest that Abyad took up her paintbrush in protest. Nearly 80 people were shot dead and many injured in the uprising sparked by government land being transferred to a Hindu shrine board, where the board wanted to construct concrete structures.

“I had never seen so much anger in people,” says Abyad, who has exhibited her work publicly and is participating in upcoming exhibitions and biennales. “It was tehreek, I thought. I saw people being beaten up inhumanely. I saw people who weren't ready to go home even after teargas shells were fired at them, people who wouldn't stop shouting 'We want freedom' until police would take them away.”

Like everyone, Abyad also experienced intense fear that she hadn't known before. “This fear turned into sadness and brought anger,” she says.

When she couldn't go out and throw stones at the soldiers, it was art that became her outlet. Without being able to speak about her anger and frustration, art showed her the way to communicate the harshest of emotions in the gentlest manner.

Her work is mostly a reflection of life in Kashmir and the events that have changed its history over the years. In her sketches, these days, she has been drawing short stories about various elements of the ongoing uprising, based on her own experience.

“Wherever there is conflict, there's discomfort, and discomfort gives rise to art,” she says.

Hussain’s early work was shaped by much more quotidian experiences. As a student at Mumbai’s JJ Institute of Applied Arts from 1971 to 1976, he would often visit home for vacation. After his education, he returned to Kashmir to introduce the graphic designer course in the Institute of Music and Fine Arts (IMFA).

“Life was peaceful, and there was so much to do as a graphic designer,” says Hussain, now a highly acclaimed artist. “I used to paint as well. We had art camps every year and artists from across the world used to visit these camps. We had great fruitful interactions with them. It would not be an understatement to say that it truly was an artist’s paradise.”

At the IMFA, opportunities were many, including the highly creative and culturally diverse environment when artists from all regions and religions would work together. “My works talked about our rich cultural heritage, expressed my admiration for the natural beauty through landscapes, photo documentation of our vernacular architecture, especially the lattice work,” he says.

Then the conflict broke out; Hussain lost all the artwork he had created in 1993 amid protests. What he managed to salvage was then lost to floods in 2014. But that has just spurred him to do more paintings like “Death and Resurrection,” a series in the form of painted relief in mixed media that shows the conflict he has witnessed.

He mourns the younger generation’s lack of awareness of an earlier Kashmir – one of his paintings, “Look Behind the Canvas,” depicts three generations of women in Kashmir – showing Mughli, whose son was forcibly disappeared, and Rafiqa, whose husband is also disappeared, and his own daughter. In the painting, he has also incorporated cuttings from the newspapers during 2010 mass uprising as a small collage.

After the work was finished, however, Hussain tore it apart, as a metaphor for Kashmir's situation.

“I was so scared to see the situation of young boys dying in 2010. I found that there is no end to this violence and situation will not be better," he says. "We are waiting for somebody to come, who can feel our wounds. I tore apart this painting but somebody will come who will put this painting back together again.”

Similarly, in July, when Abyad, a recent graduate of the IMFA, read about lead pellets being fired at civilians, the reaction came out on paper. More than 1.3 millions pellets have been fired in the first 43 days of the uprising. The hospitals are filled with young men wearing blackout glasses after undergoing operations to get out the pellets and then try to restore sight.

“We have been confined to our homes for the past 52 days with violence all around us,” says Hussain, who has also been making digital art on pellet survivors.

“It’s heartbreaking to see children losing their eye sight to pellets," he says. "Digital media is the quickest means of depicting the plight of these children to the world. Such brutal acts must be stopped."