Breaking grass ceilings: Why more women are coaching men’s teams

Loading...

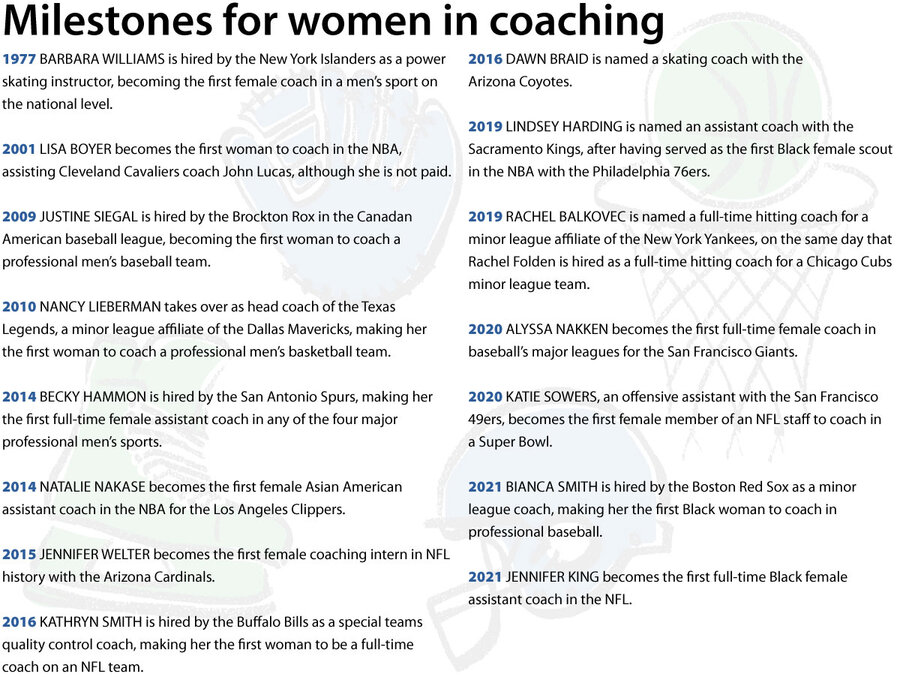

Female coaches are suddenly expanding their presence in the uppermost ranks of men’s professional sports, especially across baseball, basketball, and football. During the past 18 months alone, at least 30 women were working as full-time coaches in MLB, NBA, and NFL organizations.

While women still occupy only a fraction of such positions, their nascent movement into coaching represents what some believe could be the beginning of a second gender revolution in sports almost 50 years after the passage of Title IX. The new coaches are inspiring a generation of young female athletes, bringing greater diversity to dugouts and weight rooms, and may usher in new ways of motivating pro athletes – and even winning.

Why We Wrote This

Overcoming historic barriers, women are becoming coaches in men’s professional sports in greater numbers, bringing more diversity to one of the last bastions of male-dominated culture.

And their impact goes beyond the athletic field. Because sports occupies a hallowed place in American culture, the movement of women into coaching carries important symbolic significance.

“I think in five years,” says Justine Siegal, who once coached in men’s professional baseball, “you’ll see a major difference and you’ll see almost all programs, all the major professional teams, having female coaches in some capacity. ... We’ve changed.”

The story begins with a question about pink baseball jerseys.

Justine Siegal had been passionate about baseball since her days in Little League. She often slept with one hand gripped on her bat, in case she wanted to practice swings in the middle of the night. She played third base and pitched on her all-boys high school team. Her dream was always to take the field for the Cleveland Indians. But as she grew older and the reality set in that there was no pathway for a woman to become a professional ballplayer, she refocused.

Her new goal: become a coach.

Why We Wrote This

Overcoming historic barriers, women are becoming coaches in men’s professional sports in greater numbers, bringing more diversity to one of the last bastions of male-dominated culture.

Ms. Siegal honed her academic skills so no one could say she wasn’t qualified. She secured a master’s degree in sports studies. As she completed a Ph.D. in sport and exercise psychology at Springfield College in Massachusetts, she coached the men’s baseball team. One summer she was among a handful of women to join hundreds of men at a meeting of the Society for American Baseball Research. That’s when Ms. Siegal, during a panel discussion, asked her pointed question about professional opportunities for women in baseball.

“What is [Major League Baseball] doing for women besides selling them a pink jersey?” Ms. Siegal recalls saying. “But then I went and introduced myself to [minor league owner] Mike Veeck and said, ‘I want to coach for you.’ And he said he wanted me to coach for him. I interviewed with two teams, and the second team after, like, three interviews took me on.”

With that hire in 2009 by the Brockton Rox, then a member of the independent Canadian American Association of Professional Baseball, Ms. Siegal became the first paid female coach in men’s professional baseball. And, if a current trend of more women in dugouts and weight rooms holds, she won’t be just an asterisk in the narrative of American sports.

Female coaches – especially across baseball, basketball, and football – are suddenly expanding their presence in the uppermost ranks of men’s professional sports. During the past 18 months alone, at least 12 women in MLB organizations, 12 women in NBA organizations, and eight women in the NFL were working as full-time coaches. This doesn’t include the dozens more occupying mental skills and player development roles.

While women still occupy only a fraction of such positions, their nascent movement into coaching represents what some believe could be the beginning of a second gender revolution in sports almost 50 years after the passage of Title IX. The new coaches are inspiring a generation of young female athletes, bringing greater diversity to one of the last bastions of male-dominated culture, and may usher in new ways of motivating pro athletes – and even winning.

And their impact isn’t limited to the athletic field. Because sports occupies a hallowed place in American culture – and is where tough conversations about race, economics, and gender often happen in public ways – the arrival of women into coaching carries important symbolic significance.

“I think it is a revolution, but there’s still work to be done,” says Rachel Balkovec, who was the first female hitting coach hired by an MLB team, the New York Yankees, in 2019, after working as a strength and conditioning coach for baseball organizations for nearly a decade. “In the past year ... I felt more than ever that it’s different. We’re here, we’re supported. We’re not equally represented, but I do think we’re getting equal opportunity.”

The recent influx of women into coaching is being driven by a host of factors, not least of which is the inevitable march of history. Women have been busting through barriers in almost every profession for decades. The doors to locker rooms and film rooms just relented later than most.

“What’s happening on the coaching front is not unlike what’s happening in business, or politics, and all of these other places where we’re seeing more women entrepreneurs, more women in leadership positions, on boards,” says Courtney Cox, an assistant professor at the University of Oregon who studies race, gender, and sport. “These are fights that women have been fighting forever. And so we’re now seeing some of them able to kind of bear the fruits of that labor.”

Yet the biggest reason for the advances is the tenacity of the women themselves. Many have excelled as athletes. They have labored long and sacrificed heavily to build up experience over time, and burnished their résumés by getting advanced degrees. They have taken on short-term contracts and occupied temporary positions – all while chipping away at the glass walls around men’s professional leagues. Perhaps most important, the women who are now guiding and developing professional athletes weren’t afraid to confront the pressures and overcome the doubts of being “first.”

Ms. Siegal, for instance, became used to being the only woman in the locker room: first female coach of a professional men’s baseball team with the Brockton Rox (in 2009 in Massachusetts); first woman to throw batting practice to an MLB team during spring training with, yes, her beloved Cleveland Indians (2011); first female coach employed by an MLB team with the Oakland Athletics (2015, Arizona Instructional League).

Yet almost any woman who secures a paying job in the men’s professional leagues these days becomes a kind of pioneer. In MLB, for instance, Bianca Smith was hired in January as the first full-time minor-league Black female coach with the Boston Red Sox. In the NFL, Jennifer King was named assistant running backs coach in January for the Washington Football Team, becoming the first full-time Black female coach in the league.

In the NBA, Becky Hammon made headlines in December when she became the first woman to serve as an acting head coach after San Antonio Spurs head coach Gregg Popovich was ejected from a game. In September, Sonia Raman became the first full-time, Indian American female coach with the Memphis Grizzlies.

And that’s not counting the 2020 hire of Kim Ng as the Miami Marlins general manager, and the presence of NFL sideline official Sarah Thomas at this year’s Super Bowl – two more thresholds passed.

“Why you wouldn’t want to provide that extra ear, that different perspective, that different voice [by having a woman coach] is beyond me,” says Ms. Siegal.

Women have been helped in their rise by the changing nature of sports. As sabermetrics, big data, and other new technologies have permeated front offices and fitness rooms, teams are hiring a greater diversity of people with a wider variety of skills. During the three years Ms. Balkovec spent with the Houston Astros as a strength coach, the team was beginning to use all kinds of new gee-whiz tools, including sensors by Blast Motion that analyze swings and other activities on the diamond. She managed eight different technologies.

“It used to be just former players [who] got hired as professional coaches,” says Ms. Balkovec. “And now, well, some of our players can’t turn on a computer and they don’t want to learn how. So it’s opened up opportunities for not just women, but nontraditional hires.”

The leagues themselves have also given women a boost – belatedly, some would say. The NFL launched its annual Women’s Careers in Football Forum in 2017 as part of an intentional effort to recruit more women.

In 2018, MLB started a Take the Field program to prepare women for careers in baseball operations and on-field roles. The NBA established the Coaches Equality Initiative in 2019 to find diverse talent and build skills. The NHL followed with its own initiatives in September 2020.

It perhaps makes sense that the leagues are eager to do something for women beyond selling them jerseys, pink or otherwise. Women today account for nearly half the fans who follow big league football, baseball, and basketball, according to various league studies.

In some cases, it can be pressure as much as progressive thinking that gets organizations to embrace diversity, whether in the form of lawsuits or in the need for a change in workplace cultures.

Barbara Rayner is an ardent fan of the Dallas Mavericks basketball team who knows a little something about breaking barriers. She has often been the only woman in the room as a partner for the accounting firm Ernst & Young.

When the Mavericks hired Jenny Boucek as an assistant coach in 2018, she found the timing suspicious. It came six months after Sports Illustrated published an exposé about the Mavericks’ toxic work environment – rife with stories of sexual harassment and domestic violence.

Ms. Rayner was certainly happy with the hire, believing it was long overdue. But she remembers thinking at the time, “I wonder what it took for [Ms. Boucek] to get up to that [level]. She probably had to be twice as good, if not more, and had to clearly have the credentials in order to be able to break through to be put in that position.”

Indeed, Ms. Boucek, a former pro player herself, had 10 years of coaching in the WNBA and already had worked in the NBA as a player development coach for the Sacramento Kings.

The pathway for women to coaching has always been strewn with impediments. Consider the case of Virne Beatrice Mitchell Gilbert.

In 1931, “Jackie,” as she was called, was a minor league pitcher who achieved something few baseball players ever would: In an exhibition game against the Yankees, the 17-year-old struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in succession. A few days later baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis voided her contract and declared women unfit to play the game.

After female players had kept America’s favorite pastime alive while men were off fighting in World War II, MLB formally barred the signing of women to contracts in 1952 for the next 40 years. This ended when the Chicago White Sox drafted Carey Schueler, the daughter of the team’s general manager, in 1993. Girls weren’t allowed to play on Little League teams until 1974, either – a change that came about because of a lawsuit by the National Organization for Women.

Sports leagues continue to lag behind other institutions that were once male-

dominated – from the Supreme Court and the military to corporate boardrooms and higher education – in their gender diversity. Part of that is an entrenched practice of deferring to male applicants at all levels.

Even with the advent of Title IX in 1972, which has increased the number of girls participating in athletics by more than 1,000%, wide disparities persist in coaching. On the college level, for example, less than half the women’s teams are coached by women. The proportion of women heading men’s teams is even smaller – 3%.

Just getting their résumés to be taken seriously can be a challenge for women. “Because of gender bias, women coaches have to be usually more qualified and more competent than their male counterparts,” says Nicole LaVoi, director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport at the University of Minnesota. “[They have to] have a lot of education, a lot of athletic capital, and leverage that to be perceived as competent as their male colleagues.”

Ms. Balkovec, the hitting coach, has often recounted how she was denied low-level jobs in pro baseball because of her gender. This happened even though she had been named the 2012 Appalachian League strength coach of the year as an intern with the St. Louis Cardinals, spoke Spanish, and had a master’s degree in kinesiology.

Instead of suing for sex discrimination, however, she tried a different tactic: She changed the name on her résumé from Rachel Balkovec to Rae Balkovec. She dropped the word “softball” in front of Division I college catcher.

Hiding her gender on her application did seem to increase the number of callbacks she got. But ultimately it was her connection with the Cardinals coaching staff that landed her first full-time job as a strength and conditioning coach.

Those connections highlight another truism in the modest rise of women in professional sports: For every man that stands in the way of a woman moving into coaching, another one is usually there to encourage and mentor her.

When Jennifer Welter in 2015 became the first woman in the NFL to be hired in a coaching position for the Arizona Cardinals, many credit the vision of head coach Bruce Arians. In February, Mr. Arians made history again when he won the Super Bowl as head coach for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers with one of the most diverse coaching staffs in the NFL, including two women – Lori Locust and Maral Javadifar.

“I would hope that other owners would look and see that this works,” Mr. Arians said during a pre-Super Bowl news conference.

It’s the kind of message that advocates for women like to hear. Women should be seen as creative contributors, they say, not as intruders in the world of men’s sports.

“Every individual whether they’re male or female has their experiences to offer,” says Jessica Chin, professor with the department of kinesiology at San Jose State University. “In my mind, just teaching men that women can have authority, too, that women know about sports – that’s important.”

But an openness to diversity requires a shift in culture – away from the old-boy’s world of towel-snapping locker rooms, overt sexual harassment, and definitions of “true masculinity” tied to physical dominance. For head coaches, that means considering applicants who don’t look or think like they do.

“I think it’s easy to hire people that you know. And sometimes maybe that’s something that works against [female coaches],” says Rex Ryan, the former Buffalo Bills head coach who hired Kathryn Smith in 2016 as the first woman in a full-time NFL coaching position. Ms. Smith got the job as the Bills’ quality control coach, in part because she was familiar – she had worked with Mr. Ryan for years in an administrative position after climbing her way up from an internship in 2003.

“The main thing is your passion, your work ethic, and your accountability and team chemistry. And I think if whoever – a female, whoever – fits that, then why not consider them?” says Mr. Ryan.

Many athletes are welcoming the presence of women as coaches. This is particularly true among some of the younger players, who have grown up with modern views of gender and aren’t as steeped in the ethos of the past.

When Ms. Welter showed up as a coaching intern for the Arizona Cardinals, she already had plenty of on-field experience. In 2014, she was the first woman to play running back in a men’s professional football league with what was then the Texas Revolution of the Indoor Football League. The Revolution later hired her as a linebackers coach. She also had a master’s degree in sport psychology and a Ph.D. in psychology.

And the men she coached had done their homework. “Those guys [in Arizona] knew everything about me before I even walked in the door,” says Ms. Welter. “They’d watched my game film. They talked to people who knew me from Dallas.” But more important, they recognized the significance of her hire. “The guys were really excited to be a part of history and changing the culture within the NFL,” she says.

The lessons women have learned in grinding their way to the top pro leagues, and the different approaches they bring to the sidelines, can help them in working with their new charges. Both Ms. Siegal and Ms. Balkovec talk about the patience required to earn players’ trust.

While coaching the Sydney Blue Sox in Australia over the winter, Ms. Balkovec says, there was a veteran player on the team who was resisting a new philosophy on hitting even though he was struggling. So she spent weeks chatting with him about his family, his girlfriend, how he spent his weekends.

It paid off. One day in the batting cages, he opened up. “Finally, he asked me a question about his swing, ‘Well, what do you think I should be doing?’ And I just thought, wow, I’ve been waiting for this moment for two months.” She leaned in with statistics to pinpoint weaknesses in his swing and how to fix them.

“We won’t know if it’s made an impact until this season,” says Ms. Balkovec, “but I would say it’s made an impact in the way that he trains and his approach at the plate.”

Still, not everyone sees the presence of women in batting cages as an automatic sign of progress – including some fans. Sam Kaufman roots for the San Francisco Giants. He was surprised that the team hired Alyssa Nakken in January 2020, making her the first female coach in the big leagues. Just because she played college softball and has a master’s degree in sports management, he says, doesn’t mean she is qualified to coach baseball at the highest level.

“In any organization, especially the Giants who are coming off of far too many consecutive losing seasons, hiring a female because it’s groundbreaking might feel nice ... but as a fan, I want to maximize value everywhere I can in the organization,” says Mr. Kaufman, who works as a money laundering analyst at a consulting firm.

In the end, one question underlies this budding sports movement: How far will it go? Will there someday be gender parity in coaching? Will a female manager win a World Series championship, or hoist a Super Bowl trophy?

The women now clearing a path to a new future aren’t all contemplating such grandiose ideas. In fact, many are hesitant to talk about gender at all. Their idea of success is reaching the point where everyone – society included – judges them by their skills and talents, not their sex.

To reach that moment will require many more women coming up through the ranks, ready to guide tomorrow’s hitters and three-point shooters. Some are already trying to mold the next generation.

Ms. Siegal and Ms. Welter, for instance, are working to build the presence of women in baseball and football from the ground up. Ms. Welter runs flag football camps for girls to reinforce that they have a place on the gridiron. Ms. Siegal’s organization Baseball for All supports 40 teams of girls across the country and is working to introduce women’s baseball at the collegiate level.

“It’s a lot of work. I’ve always seen it as work for a generation. I’ve never thought it was going to be a short-term effort,” says Ms. Siegal. “I think in five years, you’ll see a major difference and you’ll see almost all programs, all the major professional teams, having female coaches in some capacity. ... We’ve changed.”

And for those revolutionary coaches still to come, no pink jerseys will be required.