To reach his flock in a crisis, one minister turns to the old tools

Loading...

| Newbury, Mass.

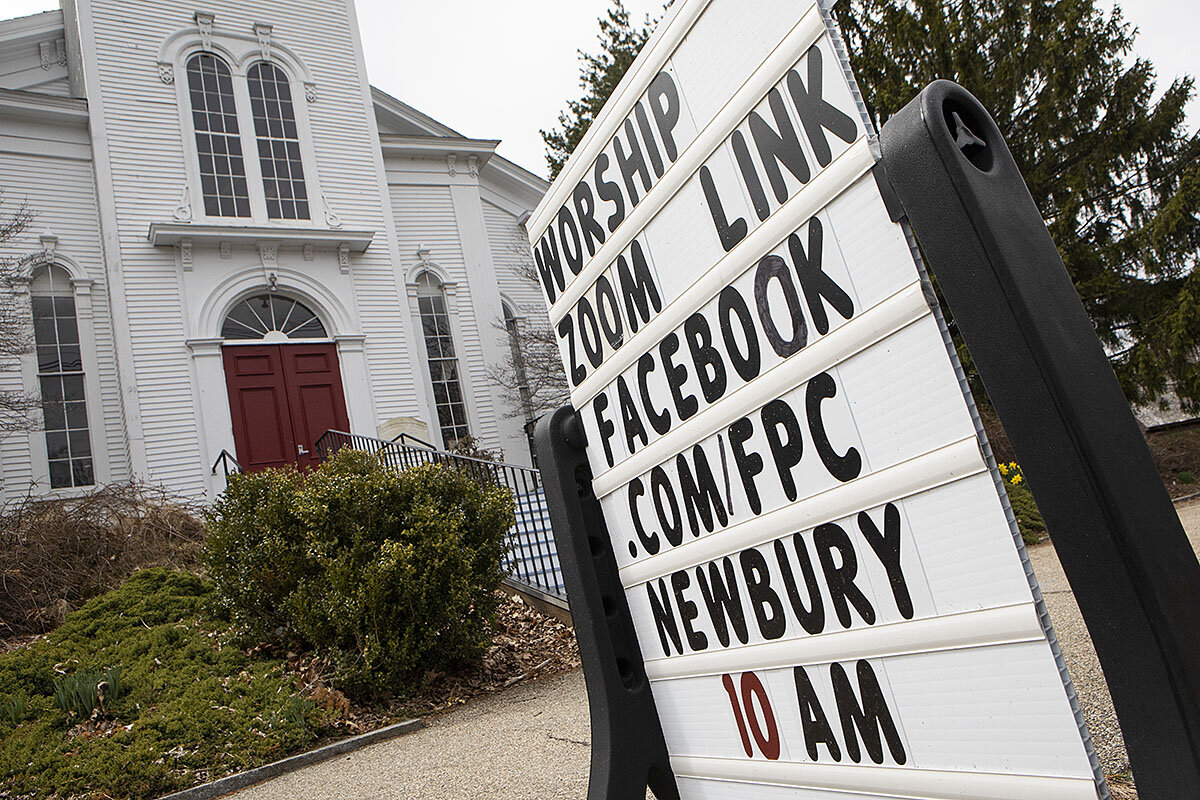

The ministry crisis began in mid-March when our town health director asked me over the phone to suspend worship services. We complied even though Sunday morning at our white-steepled, 1869 meeting house is our epicenter. When our bell rings out for miles at 9:45, it means God is soon to be worshipped and God’s people are soon to confer on all kinds of decisions that will shape our life together. Without our Sunday huddle, we’d surely feel lost in a wilderness. Yet we’d have to adapt, and our building was already needed for another purpose: feeding the hungry.

Awash in disorienting conditions, I’ve spent the past month scrambling to find ways to hold my flock together – in worship, mission, and pastoral care – without getting together physically. It feels unfaithful at times to not be like Jesus, who touched even the lepers whom others shunned. Yet distance is what love now requires, and I’m finding technology goes only so far in closing the gaps. The rest needs to come from an even older ministry toolbox, one our spiritual ancestors left for us to use in such a time as this.

Why We Wrote This

“It’s as if I lost the key to my ministry toolbox. Unable to worship in person, I can’t look out from the pulpit and see who’s dabbing eyes – or yawning for that matter,” writes our essayist. He and his parishioners have found other ways to come together in grace.

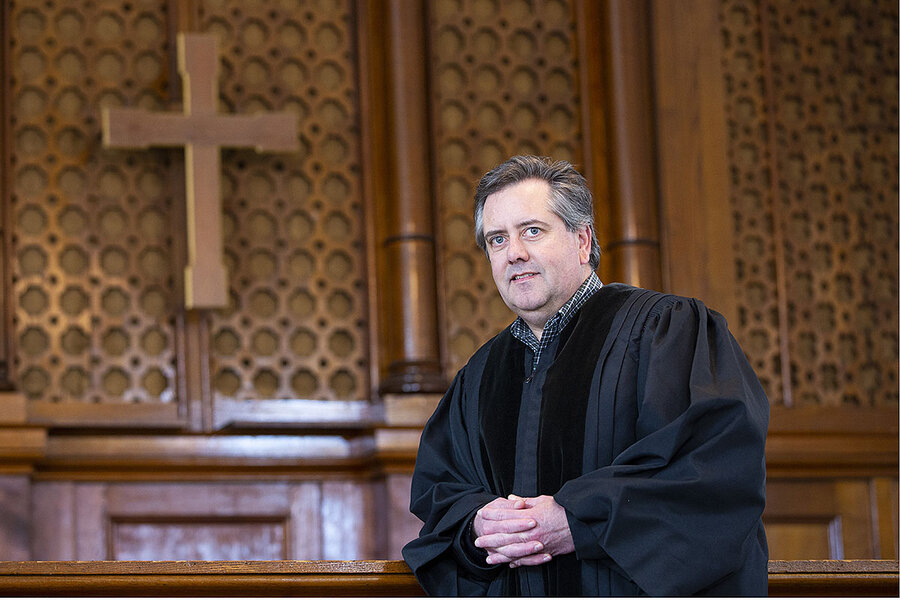

I am a pastor. I lead a Massachusetts congregation that meets for the same reasons that it was first gathered in 1635: to pray and sing, to comfort and challenge, to share food and laughter, to facilitate helping and being helped, to foster and celebrate righteousness with God. When disaster strikes, whether it’s a 17th-century drought or a 21st-century terrorist attack, we join hands and seek God. Coming together is what we do because it’s who we are.

That is, until we can’t.

The coronavirus pandemic, with its necessity for social distancing, poses challenges unlike any I’ve faced over 20 years of ordained ministry. It’s as if I lost the key to my ministry toolbox. Unable to worship in person, I can’t look out from the pulpit and see who’s dabbing eyes – or yawning for that matter. I no longer get coffee hour updates on backyard tree removals, hip replacements, or grandchildren’s sporting events. I can’t even hold hands and pray with my nursing home shut-ins. No visitors allowed there anymore. Not even clergy.

Why We Wrote This

“It’s as if I lost the key to my ministry toolbox. Unable to worship in person, I can’t look out from the pulpit and see who’s dabbing eyes – or yawning for that matter,” writes our essayist. He and his parishioners have found other ways to come together in grace.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Awash in disorienting conditions, I’ve spent the past month scrambling to find ways to hold my flock together – in worship, mission, and pastoral care – without getting together physically. It feels unfaithful at times to not be like Jesus, who touched even the lepers whom others shunned. Yet distance is what love now requires, and I’m finding technology goes only so far in closing the gaps. The rest needs to come from an even older ministry toolbox, one our spiritual ancestors left for us to use in such a time as this.

The ministry crisis began in mid-March when our town health director asked me over the phone to suspend worship services. We complied even though Sunday morning at our white-steepled, 1869 meeting house is our epicenter. When our bell rings out for miles at 9:45, it means God is soon to be worshipped and God’s people are soon to confer on all kinds of decisions that will shape our life together. Without our Sunday huddle, we’d surely feel lost in a wilderness. Yet we’d have to adapt, and our building was already needed for another purpose: feeding the hungry.

The food pantry at First Parish Church of Newbury normally feeds 75 to 125 people a week, but demand more than tripled when layoffs started skyrocketing. Food bank deliveries now arrive weekly, including one last week for 9,000 pounds. Every pew is filled with canned vegetables, rice, and other basics for drive-thru and home deliveries. Though I serve the church part-time and live 45 minutes away, I still wanted to support this volunteer-run operation that had suddenly expanded to take over the whole sanctuary. But how?

At first, I acted instinctively and just showed up. Keeping six feet apart, I folded cardboard boxes and encouraged this monumental effort to provide for our area’s most vulnerable. But organizers didn’t need or want extra bodies around as health precautions got stricter week by week. So I stayed home and borrowed a page from an old ministry playbook that says in effect: Let the people testify. I posted volunteers’ photos, passed along their updates via e-newsletter and put them in touch with news media who reported what they’re doing and what motivates them. Making room for witness is what our forebears might call it. They were onto something.

Meanwhile, we’re still a small church with a big problem: no physical place to gather. Our solution involved moving worship online to Zoom, where videoconferencing lets us see our 25 regulars and hear their prayer requests. It’s not perfect – our music sounds better in our sanctuary than online – but being virtually together makes up for many a trade-off.

Getting everyone to Zoom has been a bit like moving a 19th-century caravan through a mountain pass. Several hopped on easily, but some would need to go back and assist stragglers. Two have no computers at home. A bunch more can’t stand technology: It escalates their anxiety in what are already anxious times. These are folks who love to help others and don’t like being on the receiving end of handouts or tutorials. So I tried an old-school ministry move: I picked up the phone and called to check on everyone.

I had been using the phone less and less in an age of texting and instant messaging, but now it was a rediscovered treasure in my hand. Sure, I offered tips for using Zoom, but more than that: I listened. In quivering voices, I heard fears about being high-risk for complications of COVID-19. I heard confessions that had pent up with no ears to hear them out. One parishioner called me back within a few hours, just to talk again. The tech issues are now largely resolved, but the calls have continued. They’ve been a grace connecting me with my flock on a new, more personal level.

Preaching online, I’ve learned, is a distinct craft with its own learning curve. To my surprise, the ancestors’ toolbox has come in handy here too. I’d never realized how much my preaching feeds off energy from my congregation until I started giving sermons from my home office. Now I’m speaking into a computer camera while the entire crowd listens on mute. Though Congregationalists are jokingly called the frozen chosen, mass muting takes their reticence to a whole new level. Without the usual feedback cues signaling me to embellish here or fast forward there, I crave new props to help me be sure folks are still engaged, not dozing off.

For that, I’ve started putting art on PowerPoint slides, which I’d never used at the meeting house. Much as Europe’s cathedrals once relied on stained glass to bring biblical stories to nonreaders, I’m finding illustrations can poignantly reach the frazzled, the stressed out, and the easily distracted in pandemic times. In Easter season, we will look together at how masters like Renoir, Raphael, and Caravaggio depicted the risen Christ. With that cloud of artistic witnesses with me, I feel synced with the saints even when I’m preaching alone. I’m reminded once again that I’m part of a team, a Communion, that transcends space and time.

I haven’t had to give up all embodied ministry. When I heard a longtime parishioner was receiving end-of-life care at her nursing home, I got permission to see her under an exception for the dying. Wearing a mask, I led the family in a farewell rite. I marked her forehead with the sign of the cross. I trusted she could hear me and knew the vibrations in my voice as those of her earthly shepherd, pointing her safely to a final peace with God. It felt good to draw again on my familiar toolbox in a moment when it mattered.

Someday this pandemic will relent and we’ll do ministry again as people for whom the Incarnation is a guiding truth. By then our pastoral repertoires will be wider and deeper, thanks to those who left us tools we never expected to need again.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

G. Jeffrey MacDonald is pastor of First Parish Church of Newbury, UCC. His second book, “Part-Time is Plenty: Thriving Without Full-Time Clergy,” was published this month.