What the March for Our Lives looked like through the eyes of young reporters

Loading...

| Washington

As a young journalist it can be tough sometimes not to feel like a nosy kid with too many questions.

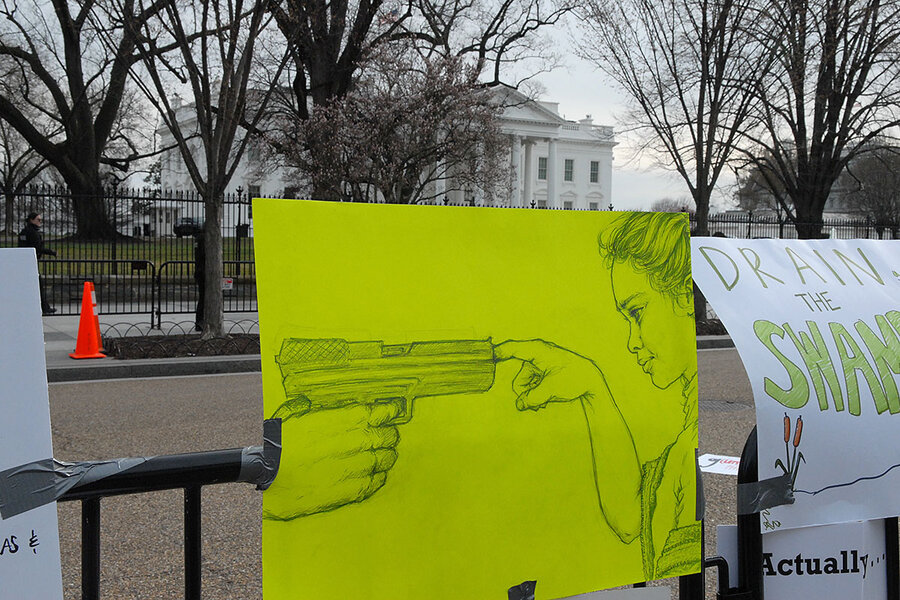

The March for Our Lives in Washington was a major political event, of course, and many people came expressly to make a statement. But there was a hopeful energy among the teenagers there that they weren’t used to seeing.

For many young protesters, this was their first political action. They knew which candidates they wanted to support and which they wanted to challenge. They could list the gun control policies they wanted to implement. Their presence along Pennsylvania Avenue, climbing the walls of embassies and government buildings – the literal pillars of US democracy – to view the stage felt meaningful. They were also eager to talk to reporters.

The Monitor sent a group of us – two college students and three recent college grads – to cover the marches in Washington and Boston. The paper turned over its social media accounts to us on Saturday to give readers a sense of what a youth-led movement looked like through our eyes. Here are the moments that stood out to two of us, both interns, who covered the D.C. march.

***

Noble Ingram: I spoke with Kateri Daffron, 13, from Anadarko, Okla., whose school narrowly avoided a shooting when a student brought a gun to campus in January. Her small town had long faced gun violence, she explained, and the recent scare there motivated her to come to the Capitol.

“I’m here because I believe in protecting my friends at school,” she said. Then she shook my hand, stepped beside me, and posed for a photo taken by her mother. Speaking with a journalist was part of her growing political voice and she wanted to remember it. At that moment, I didn’t feel so nosy.

***

Rebecca Asoulin: I mentally ran through the basics before I approached marchers in Washington: Who are you, why are you here, what do you want? A checklist I learned in high school journalism when I thought flowery language was the coolest thing, like ever.

Now I know better, mostly.

For the first time since I started reporting, I was thrilled if high school students recognized 23-year-old me as one of their own. Or at least almost one of their own. Noah Keckler, a Louisville, Ky., high school journalist, did punctuate each of his sentences with a “Yes, ma’am.”

We could learn a lot from young people right now. Especially about how to be authentic – in all our contradictions and complexities.

Ryan Deitsch, a Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School senior, embodied this last week after a panel discussion at Harvard University. His fire-engine red hair is as real as his speaking style.

Ryan hadn’t packed for his train to Washington that night. I scrambled after him as he was rushed out the door, speed talking over his shoulder about meeting earlier that day with political leaders.

“A lot of [the dialogue] wasn’t the free and original thought that I had hoped it would be," he said.

Ryan corrected himself during our three minute interview. He acknowledged potential gaps in his knowledge. He asked questions. He pushed back.

In politics, people see changing one’s opinions as equal to lying. The Parkland students stay on their message, but they also set aside their ego, and treat themselves and each other with a love that allows for immediate self-reflection and correction.

In our conversation, Ryan was, in short, eager to learn.

Maybe it’s time for me to start thinking more like I thought in high school. And to add another line to my mental checklist: Approach people with love.

***

N.I.: These teenagers seemed to have taught something to adults, too. Seeing their children face gun violence head-on was a call to action, older protesters repeated to me.

“The Parkland student leaders inspire me greatly on a personal level. There have been adult leaders that have tried to advocate for gun reform... but it was not until these student leaders spoke for themselves that all of us that were somewhat silent... woke up,” said Neil Willenson, who came to the march with his children from Milwaukee, Wis.

Janice Shingler echoed that sentiment. Ms. Shingler has lived in Washington her whole life and first began speaking out about gun violence 32 years ago, when her twin brother was shot and killed. The power of the Parkland students renewed her focus, she said.

“I’m hopeful. I also feel sad that it got to this point that now our children have to stand up. We all need to stand up. We should be marching every day,” she said.

There is a kind of surprise sown beneath these words. No one expected teenagers to organize a political rally drawing hundreds of thousands of protesters.

“The youth are told that we are the future, children are the future. But we’re never told when,” Ryan told me after the Harvard panel discussion. The answer may be now.

***

R.A.: Sisters Maddie Humphries, 10, and Destiny Clark, 11, stood on a bench, signs held over head above the streaming crowd in Washington.

“I want to stick up for all the children who have lost their lives and for all the children who think they’re going to lose their lives every time we do a lockdown drill. I don’t want them to think that. I want them to think that they’re safe,” says Destiny.

She and her sister cuddled with their mom as I snapped a photo in awe of an 11-year-old who framed an issue – that could have been about fear – about love.

It is a framing the Parkland students themselves emphasize. Stoneman Douglas student David Hogg spoke about love at the Harvard forum, with fellow #neveragain activist and student Cameron Kasky embracing him and five other peers smiling fondly at him.

“It’s hate and fear and it’s anger on both sides of the political spectrum that got us to this point and it’s not what’s going to solve this,” said David. “We can use love and compassion to emotionally empower us and continue this fight for good and justice.”

A few blocks up from the rally’s main stretch on Pennsylvania Avenue, Michelle Phalanukorn was the last person in a line of more than 50 holding up the photos and names of every school shooting victim since 1966. They took up an entire city block.

Her organization, the Family Resource Associates in Shrewsbury, N.J., only had five people in Washington. Dozens of other people had seen the chain of photos and offered to stand for five minutes, 10, an hour, or two. In the shade. Or in the sun.

“I didn’t have expectations [for the march],” Ms. Phalanukorn says. “I just had hope.”