With Elizabeth Warren out, women voters ask: ‘What now?’

Loading...

Is America still not ready for a female president? Elizabeth Warren’s decision Thursday to suspend her candidacy left only one of the record six women who entered the Democratic race still standing – a very distant Tulsi Gabbard.

With Hillary Clinton, it was understandable, Warren supporters say: She had baggage. Donald Trump was a wild card. But could it be pure coincidence this time around that voters didn’t go for any of these women, including the former California attorney general whose questioning of Brett Kavanaugh garnered her a national spotlight; the most effective Democratic senator in Congress, who won 42 Trump counties in her state; or the Harvard Law professor who predicted the financial crisis of 2008 and then spearheaded the effort to protect consumers?

Why We Wrote This

What will it take to crack the final glass ceiling in U.S. politics? That’s the question women voters are asking after a record six women ran for president and fell short of the nomination.

Michelle Wu, a Warren Senate-campaign staffer who in 2013 was elected to Boston’s 13-member city council, says that’s all the more reason why passionate, visionary women should run.

“We need to translate that anger and disappointment into resolve to step up,” says Ms. Wu. “It’s not just one seat every four years ... The more women are serving on city councils and as governors, the more that also changes who we think could be president.”

Elizabeth Warren made a pinky promise that America couldn’t keep.

And for many girls, that is devastating. Not just for the ones in pigtails who met Senator Warren in selfie lines, wrapped their little finger around hers, and vowed to believe that a woman could be president. But also for the big girls in business suits – the CEOs and the mothers who told their daughters “dream big” as they tucked them into bed. They thought finally, here was a candidate so smart, so passionate, so competent that at last, they would see this dream come true.

And then they didn’t.

Why We Wrote This

What will it take to crack the final glass ceiling in U.S. politics? That’s the question women voters are asking after a record six women ran for president and fell short of the nomination.

Instead, they saw a janitor’s daughter turned Harvard law professor emerge from her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, into the almost-spring sunshine and drop out of the 2020 race before the buds had a chance to blossom. She leaves two septuagenarian white male frontrunners and a very, very distant Tulsi Gabbard in a field that began as the most diverse in history with six women candidates.

With Hillary Clinton, it was understandable, Warren supporters say: She had baggage. Donald Trump was a wild card. But could it be pure coincidence this time that voters didn’t go for any of these six women, including the California attorney general whose questioning of Brett Kavanaugh garnered her a national spotlight; the most effective Democratic senator in Congress, who won 42 Trump counties in her state; and the Harvard Law professor who predicted the financial crisis of 2008 and then spearheaded the effort to protect consumers?

Then a woman asked the question on so many people’s mind: What role do you think gender played in this race?

“If you say, ‘Yeah, there was sexism in this race,’ everyone says, ‘Whiner!’ ” Senator Warren said. “And if you say, ‘No, there was no sexism,’ about a bazillion women think, ‘What planet do you live on?’ ”

Some 29 countries currently have a woman leader. Since 1950, women have led 75 countries. Just not the United States.

“The real concern is that people will say, why bother? If we don’t bother, and if women don’t run, they can’t get elected. So it’s never going to change if they give up,” says Kathleen Dolan, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. “Maybe feel badly for a few weeks and then maybe people who advocate for women candidates will get up and start working again.”

Boston city councilor Michelle Wu, a former student of and campaign staffer for Senator Warren, is one of those advocates – arguing that her mentor’s defeat should not deter but rather motivate passionate, visionary women to run.

“I know that it is infuriating and incredibly discouraging, but we need to translate that anger and disappointment into resolve to step up,” says Ms. Wu, who was one of only two women on Boston’s 13-member council when she was elected in 2013 and is now joined by half a dozen women councilors. “It’s not just one seat every four years. … The more women are serving on city councils and as governors, the more that also changes who we think could be president.”

Someone to ‘lead us out of the abyss’

But there’s a more difficult question, one which a woman who just poured her heart into a year-long campaign doesn’t answer before going back into the sanctuary of her home, which is: Even if there is a higher hurdle for women to clear en route to the White House, is that the main reason why Senator Warren’s campaign came to a creaking halt?

“There are reasons that candidates lose and men lose all the time,” says Professor Dolan. “Nobody looks at Cory Booker and says, ‘Why does that man fail?’ ”

But Warren supporters aren’t thinking about Cory Booker right now, or political science research. They are too sad. They need a moment.

In their minds, if someone had designed the perfect liberal female candidate, it would have been Elizabeth Warren. After Secretary Clinton’s loss in 2016, Senator Warren got them back on their feet, convinced them it could be different this time. She was the happy warrior, the best candidate they’d ever seen. If any woman could shatter that last glass ceiling in American politics, she could.

Now they’re left feeling that nothing will ever be good enough, no woman will ever get to the White House. Or not while they’re still around to see it, at least.

“It makes me so very sad,” says Mabe Wassell, an Illinois voter who had come to see the senator in a fluorescent-lit gym in Davenport, Iowa, across the Mississippi River not two months ago. “By the time I get to vote [on March 17], I get to vote for the lowest common denominator … two old men.”

“I feel the pain she might feel ... the feeling of being rejected, when I know she would have been an amazing, amazing leader,” says Caroline Yang, a Korean-American in Lexington, Massachusetts. She says she can relate to being discriminated against, having been passed over for the presidency of a local nonprofit in favor of a white person. “There is a certain bias against her that I think is unfair.”

It’s not just about advancing women, though. It’s about this extraordinary time in American politics.

“A lot of us, including myself, are feeling incredible anger and disappointment and sadness about the outcome of this primary,” says Debra Feldstein, who started a Women for Warren Facebook group dubbed the PerSisters. “Elizabeth Warren was probably one of the most qualified candidates we’ve had in recent history to lead us out of the abyss we’ve been led into by Donald Trump.”

‘Electability’ and the last glass ceiling

Ms. Feldstein lives in Santa Cruz, California, a coastal city of surfers and college kids that she calls “Bernie country.” His supporters are very outspoken, so much so that she thought she was alone in her choice of Ms. Warren. Then, one by one, her friends whispered that they, too, actually preferred the Massachusetts senator, but they planned to vote for their second choice because they considered her unelectable.

After more than a dozen of these conversations, Ms. Feldstein started the PerSisters Facebook group to give fellow Warren supporters a sense of community. In just two weeks, it grew to 856 women around the country.

But ultimately, it wasn’t enough. Senator Warren won fewer than 10% of the delegates that Sen. Bernie Sanders and former Vice President Joe Biden each collected on Super Tuesday, coming in third in her home state of Massachusetts.

“I think a lot of people didn’t vote their conscience because of fear,” says Ms. Feldstein, a consultant for women-led organizations who says there’s no question in her mind that a man with Senator Warren’s qualifications would have become the nominee. “There’s a view that people in our country hold, even women, of what looks and sounds like a president.”

Professor Dolan, author of the 2014 book, “When Does Gender Matter?,” says if you ask people why they don’t like the senator, they’ll say she’s hectoring or bossy. “These are the same people who are like, ‘Oh Bernie, he’s so passionate,’” she says.

But she also points out that Hillary Clinton, “who arguably had the most baggage of any woman who has run for president,” still got 3 million more votes than President Trump and did as well among Democrats as he did among Republicans.

There are many factors in elections. Gender is just one of them, she says, citing research that shows that women win as often as men when they run, and that the gender of candidates plays a minimal role in determining voters’ choices. But there’s also a wild card factor in this race.

“Donald Trump has broken everything about American government and American politics. And he has broken presidential elections … to the point that all Democrats care about is beating him,” says Professor Dolan. “Democrats are paralyzed with fear and they simply want to know who’s going to beat Trump. But the problem is, nobody knows who’s going to beat Trump.”

“They wanted the sure bet”

Surely Senator Warren could, the way she pilloried Michael Bloomberg on national TV and demanded that he unmuzzle the women who had lodged sexual harassment and discrimination complaints against him, her supporters say.

They blame the media for ignoring her, though there are quantitative challenges to that argument. They blame men – why can’t they be as enlightened as in Scandinavia? They blame other women, who they say were intimidated by someone as strong as Senator Warren. They blame political calculation over voting one’s conscience.

“People kept saying, ‘I can’t just follow my heart, I have to do the right thing,’” says Camille Brown, a New Hampshire voter. “And the right thing involved somebody else – because they wanted the sure bet. It’s too bad that people can’t just vote for the person who is the best candidate.”

But they have no regrets about their choice. And neither does she.

And maybe, they will find solace in signs of progress: in six women running for president this year, and what looks likely to be a record number running for the U.S. House and Senate, building on 2018’s record number elected.

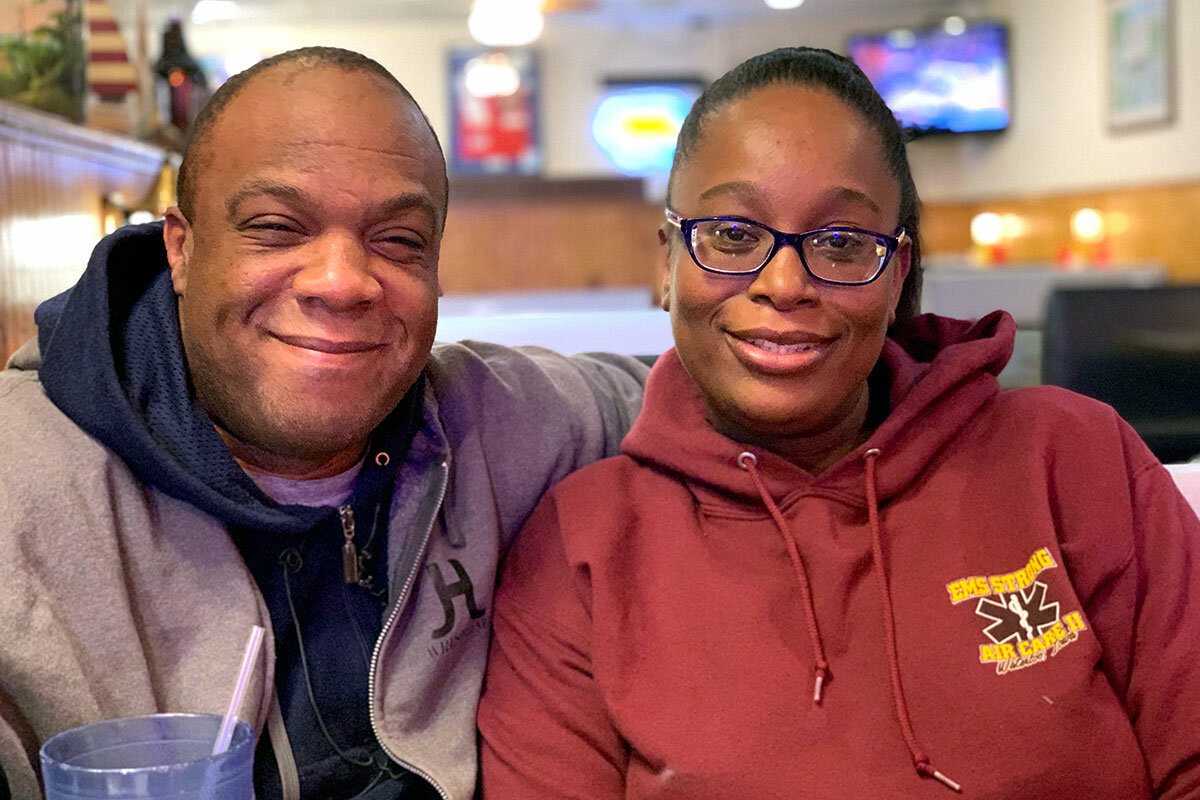

“Even though she is out of the race, what she’s done is really life-changing for me, especially because I’ve never been involved – but also people around me,” says Bridget Saffold, an African American woman who hosted the first-ever house party for a presidential candidate in her black community of Waterloo, Iowa, drawing 300 people to hear Senator Warren.

Many of those people had never been engaged before, including her best friend. Ms. Saffold has watched her go from the sidelines to the front lines, caucusing for the first time, finding her voice, and getting increasingly involved in city politics.

And then there’s all those younger girls the senator has inspired, like Karina Beltran, a high school junior in Los Angeles who got the news in the middle of sociology class.

“As soon as class ended, I got on Twitter and my eyes got watery, and my friends were like, ‘Are you going to cry?’ And I was like, ‘No, I’m not!’” she says. She did tear up later though. She had a lot invested in this race – and not just the dog-walking money she donated to the campaign. “I really hope I’ll be alive for the first woman president,” she says.

“One of the hardest parts of this is all those pinky promises and all those little girls who are going to have to wait four more years,” Senator Warren said Thursday, looking up in such a way that her friends might have asked her, are you going to cry? No, she didn’t.

The fight is still on.