Behind legal fight over religious liberty, a question of conscience

Loading...

When Bruce Springsteen canceled his concert in North Carolina in April to protest that state’s new transgender bathroom law, he followed his conscience.

Mr. Springsteen understood that his choice would cause economic harm to people whose jobs were associated with the show. But he decided to follow his highest sense of what is right to stand in solidarity with the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community.

“Some things are more important than a rock show,” Springsteen said in a Facebook post. “It is the strongest means I have for raising my voice in opposition.”

In essence, Springsteen refused to use his creative talents in North Carolina because of his moral objection to the state law.

Religious conservatives are citing the same right of conscience in their opposition to government-required involvement in same-sex wedding ceremonies – celebrations that they say violate their highest sense of what is right.

Now, the issue of freedom of conscience is at the center of an escalating national confrontation between advocates for gay rights and religious conservatives.

At its most basic, the conflict pits two competing constitutional values.

On the LGBT side is equality and equal protection mandated under the Fourteenth Amendment and in 22 state statutes that prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

On the religious conservative side are liberties guaranteed to each individual, upholding rights to religious exercise, free speech, and freedom of association.

The conscience issue has arisen most prominently in a few high-profile court cases involving wedding vendors – cake designers, florists, photographers – who say they are barred by their conservative religious beliefs from playing any role supporting a same-sex wedding.

Gay rights advocates insist that there can be no exemption from antidiscrimination laws to permit business owners and others to refuse to serve same-sex couples. They say it would be no different than allowing a restaurant owner to refuse to serve African-Americans.

Religious conservatives reply that without an exemption, they will be forced to choose between remaining faithful to God or complying with a government command.

Springsteen has a right to refuse to serve concertgoers in North Carolina as well as to refuse to play at events sponsored by the Southern Baptist Convention, says Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the convention.

“I would not want any law that would compel Bruce Springsteen to perform at the Southern Baptist Convention if he morally objects to what we believe,” he says.

“The question then becomes: Are we going to use the power of the state to essentially bully people out of their businesses because they don’t want to violate their consciences?” he asks.

• • •

The right of conscience has been described as the ability to respond faithfully to that “still small voice.” It is a moral manifesto – an acknowledgment of a desire to be obedient to a higher authority, even when in direct conflict with the man-made rules of the majority in modern society.

It is the same constitutional principle that helped pacifist conscientious objectors avoid being forced by the draft to wage war, helped Jewish merchants stay open despite Sabbath observance laws, helped win exemptions from vaccination and blood transfusion requirements for certain religious minorities, and helped allow medical professionals to opt out of performing abortions rather than violate their religious belief about when and how life begins.

It is a concept that has ebbed and flowed throughout American history.

“The framers of the Constitution saw and experienced that government suppression of religious activity – not just belief, but activity – had caused real suffering to people and resentment and division as a result,” says Thomas Berg, a professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis.

“They saw that the religious impulse was something deeply central to human identity – the impulse to seek, and follow, and love some sort of higher power or ultimate reality,” Professor Berg says. “That impulse is still here today.”

But the professor warns: “If society doesn’t proceed carefully, it will learn again about the kind of suffering and division that can be caused by unnecessarily preventing people from acting consistently with their faith.”

Advocates for LGBT rights oppose recognition of a broad right of conscience for religious conservatives that might justify exemptions from antidiscrimination laws. Such an exemption would send a message that gay men, lesbians, and transgender Americans are less than full citizens, they say.

“We don’t provide exemptions under current nondiscrimination laws when it comes to public services and places of public accommodations – for any reason,” says Sarah Warbelow, legal director at the Human Rights Campaign, an LGBT rights organization.

“The expectation in a business setting is that you treat all your customers the same,” she says.

The difficulty in refusing to grant a religious exemption is that the burden falls squarely on religious conservatives who will either be forced out of business or coerced by the government to violate principles of their faith.

On the other side, the difficulty in requesting a religious exemption in the context of same-sex marriages is that the burden falls squarely on same-sex couples who would otherwise be entitled to equal treatment.

“We’ve never had religious exemption claims that we’ve accommodated where the claim is: I don’t really want to interact with you, I don’t want to do business with you, I don’t want to give you this government service you are entitled to,” says Douglas NeJaime, a University of California at Los Angeles law professor and faculty director at the Williams Institute, a leading research organization on issues involving sexual orientation.

“That’s not just about what you do in your religious community, it is about living in the broader society,” he says. “Over the long term, people are going to come to see LGBT people as equal members of society and discrimination in those aspects is not going to be tolerated. But I don’t think we are at that point yet.”

Antidiscrimination laws help transform society and foster greater acceptance of full rights for gay men and lesbians, LGBT advocates say. Granting religious exemptions would fuel ongoing opposition to those rights and would likely spawn more aggressive efforts to win an even wider array of exemptions.

Look at the ever-expanding debate over abortion-exemption measures and contraceptives, they note.

Others embrace a more basic approach, urging religious conservatives to re-read Bible passages dealing with sexuality, reconsider their views about gay marriage, and above all to follow Jesus’ command to “love thy neighbor.”

Many people on the gay rights side of the debate simply don’t understand what it means to be motivated by deeply-held religious beliefs, says Mr. Moore.

“I have to explain that they actually believe they are going to stand before the judgment seat of Christ and give an account of how they’ve lived their lives,” he says, referring to the beliefs of evangelical Christians.

Other analysts stress that efforts to change someone’s religious convictions by coercion almost always fail.

“Beliefs may change because of persuasion, they may change because of contemplation, but when the change in beliefs is worked by an external [coercive] force, saying, ‘You do this,’ the religious believer can’t perceive that as any kind of organic change in one’s understanding of what God wants,” says Berg.

“That’s just an attack on a fundamental feature of your identity.”

• • •

The big question in cases pitting same-sex couples against conservative wedding vendors is whether courts will recognize and enforce a religious right to conscience.

The trend runs decisively in one direction. Courts in New Mexico, New York, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington State have uniformly rejected claims of conscience by wedding vendors. No court has ruled in favor a wedding vendor seeking a religious exemption from an antidiscrimination law.

One state court in Kentucky has ruled that a Christian-owned printing company could decline to print T-shirts for a gay pride event. Other than that decision, the legal score card in wedding cases runs against religious conservatives.

It suggests that perhaps the right of religious conscience isn’t garnering the respect it once enjoyed within the judiciary.

In the broad confrontation between religious conservatives and LGBT advocates, lawyers are embracing starkly different legal precedents to support their cases.

One of the United States Supreme Court’s best known decisions involving protection of religious conscience was handed down in 1943.

Two children, members of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in West Virginia, argued that their school’s mandatory order to salute the American flag violated the biblical injunction against worshiping a graven image.

The 8-to-1 decision reversed a high court ruling only three years earlier that required children in the Jehovah’s Witnesses faith to participate in the daily flag salute or face expulsion from school and other punishment.

The earlier court had found that the school’s flag salute would foster patriotism, which was deemed an essential element of national security at a time when a militant Nazi Germany was on the rise.

By 1943, when Justice Robert Jackson wrote his decision in the second case, the fate of the world literally hung in the balance as World War II raged in both Europe and Asia. But Jackson pushed aside claims that national security necessitated a strict uniformity of thought that would require schoolchildren to violate their religious faith.

“If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein,” Jackson wrote. “If there are any circumstances which permit an exception, they do not now occur to us.”

While Jackson’s 1943 landmark decision might provide a rallying point for religious conservatives, LGBT advocates are focusing on a different kind of legal precedent.

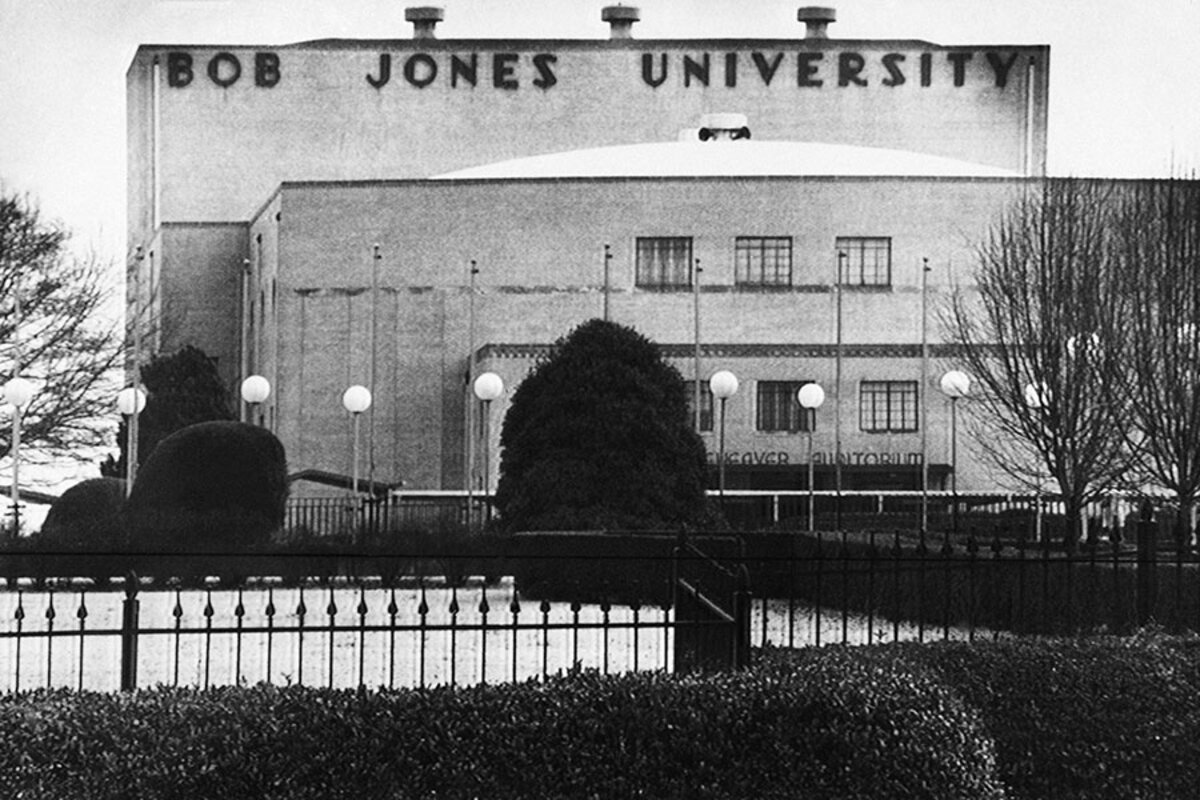

In 1983, the high court took up a dispute examining whether Bob Jones University, a conservative religious college in South Carolina, was entitled to claim tax-exempt status despite banning interracial dating and marriage.

The Supreme Court ruled 8 to 1 that the Internal Revenue Service acted properly in revoking the school’s tax-exempt status. The court rejected the university’s argument that its policies were grounded in sincere religious belief. Instead, the court said the government had a fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education.

“That governmental interest substantially outweighs whatever burden denial of tax benefits places on petitioners’ exercise of their religious beliefs,” then-Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote in the majority opinion.

LGBT advocates are hoping that courts will apply the same antidiscrimination reasoning to cases involving clashes between religious conservatives and LGBT people.

If courts begin making that connection, the legal precedent will lay the groundwork not just for decisions in wedding vendor cases but potentially for direct challenges to the tax-exempt status of every religious organization in America with policies that reflect traditional religious beliefs about same-sex marriage that are viewed as discriminatory by the government or private plaintiffs, analysts say.

Such a legal precedent might apply to the full range of government benefits, grants, and programs received by all faith-based organizations with traditional policies on same-sex marriage.

“I don’t think you are going to see, at least in the near term, a heavy-handed federal government push to shut down institutions like Christian colleges and universities,” says John Inazu, a professor at Washington University Law School in St. Louis and author of the new book “Confident Pluralism.”

But it could be in play in the longer term, he says. For now, he adds, “You will see lots of cultural pressure and lots of saber rattling.”

• • •

Every debate over religious exemptions in the context of LGBT rights almost immediately turns to an analogy with racial discrimination.

In the deep South in the 1950s and early 1960s, some people who opposed equal rights for African-Americans argued that it would violate their religious faith to be forced to treat African-Americans on equal terms with whites.

“If we look to the historical record, many Americans had real religious objections to interacting with people of color, to allowing interracial marriages,” says Ms. Warbelow.

Such religious justifications in the context of race have been uniformly rejected in the courts as well as in the court of public opinion.

Now, gay rights advocates argue that there is no difference between refusing to serve an African-American because of skin color and the belief by religious conservatives that to become personally involved in a same-sex wedding ceremony would be sinful.

“The courts have said over and over again that we really need to make sure that all of our citizens are being treated equally under the law, that nobody is being disfavored,” Warbelow says.

Professor NeJaime says it is not surprising that certain commercial businesses and some government clerks who issue marriage licenses are asking for exemptions. But granting them would be unprecedented.

“Often you have a generally applicable law, like racial segregation, and then when that law changed then you see laws promoting racial equality and you have claims in the wake of that for exemptions.”

Analysts on the conservative religious side of the debate reject such parallels with race.

“It is a completely illegitimate comparison,” says Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention.

“We had an oppressive state-sanctioned Jim Crow regime of state-approved terrorism in the South, systematically oppressing African-American people,” he says. “That is not what is taking place in the wedding industry right now.”

Moore says the debate is not about who will be served, the debate is about what marriage is. The question is whether a religious conservative business owner can be compelled to perform services for an event that his or her religion views as sinful and immoral, he says.

“That is not a question of some form of systematic persecution of people,” Moore says. “It is someone saying, ‘I can’t in good conscience be part of this particular religious ceremony.’ ”

To Moore, the issue is fundamental.

“Freedom of conscience and free exercise of religion is something that God has embedded in humanity. So when we recognize the freedom to believe and to act on those beliefs we are simply affirming human dignity,” he says.

Religious liberty is not a privilege doled out by government, but a right granted by God, he says. It is a reminder that there are important limits to government power, he says.

For Moore, the current confrontation is a warning about government overreach and abuse of power.

“A state that can compel people to do what they believe to be sinful is a state that can do anything.”

• • •

Part 1: How the push for gay rights is reshaping religious liberty in America

Part 2: A florist caught between faith and financial ruin

Part 3: Behind legal fight over religious liberty, a question of conscience

Part 4: In Mississippi gay rights battle, both sides feel they are losing

Part 5: Is wedding photography art? A wrinkle in religious liberty debate.

Part 6: For those on front lines of religious liberty battle, a very human cost

Part 7: A push to help gay couples find wedding joy – without rejection