Europe’s schools face new test: Teaching safely in a pandemic

Loading...

| Berlin; Paris; and Hillerød, Denmark

Two months after most countries in Europe began closing down in response to the coronavirus, many are cautiously reopening schools alongside their economies, welcoming tens of millions of students back into the classroom in staggered shifts. Denmark was the first to reopen schools in mid-April, followed by France, Germany, Austria, and others.

European governments have been unrelenting with logistical and sanitary requirements. But most countries have otherwise allowed schools to make their own decisions about how lessons should be delivered and physical space partitioned. And they have put a premium on creativity and patience in an environment that has changed vastly since before the shutdown.

Countries are weighing a combination of factors that include science, besides elements such as cultural priorities, as they work out the best path forward. “No one knows exactly what’s going to happen,” says François Dubet, a sociologist and professor emeritus of the University of Bordeaux. “If the number of sick people goes down, we’ll return to normal life, but if in 10 days that number goes up, it’s going to get very complicated.”

Why We Wrote This

Getting children back to school is a top priority in most countries as they ease their pandemic lockdowns. But they are taking a variety of different approaches to reopening classrooms.

Henrik Christensen looks tired.

Ever since the Danish government decreed its youngest children could go back to school, the principal of Marie Mørks School has been up late, planning logistics and sorting how to communicate with the families he serves. The youthful father runs a private school 30 miles north of the Danish capital of Copenhagen, and, with a toddler at home and a 12-year-old at the local public school, he understands the anxiety around bundling kids off to school during a pandemic.

“Of course, you are a bit nervous,” Mr. Christensen says. “But the children have missed school and their friends, and for them a month is an eternity. Their smiles take away most of my fears and reservations.”

Why We Wrote This

Getting children back to school is a top priority in most countries as they ease their pandemic lockdowns. But they are taking a variety of different approaches to reopening classrooms.

Two months after most countries in Europe began closing down in response to the coronavirus, many are cautiously reopening schools alongside their economies, welcoming tens of millions of students back into the classroom in staggered shifts. Denmark was the first to reopen schools in mid-April, followed by France, Germany, Austria, and others. Parents expressed concerns about their children’s health, while teachers worked overtime to serve both students in classrooms and those at home who are waiting for a return date.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

In Denmark, logistics around hygiene have been painstaking. Door handles, washbasins, and school tables are wiped down three to five times daily. Classes have been halved, so students can maintain a 2-meter (6-foot) distance. Outdoor spaces are subdivided into five units, with each class appointed one portion during recess.

Even Legos posed a challenge, explains Mr. Christensen – “until a math teacher came up with a brilliant idea!” The Legos are now separated into four boxes, he says, with each set in use only every fourth day, since the virus is believed to die out after 48 hours on solid surfaces.

Indeed, European governments have been unrelenting with such requirements, and officials are watching health metrics closely. But most countries have otherwise allowed schools to make their own decisions about how lessons should be delivered and physical space partitioned, putting a premium on creativity and patience in an environment that has vastly changed since before the shutdown:

- In Germany, one Berlin school has divided each class into four groups to maintain a required 1.5 meters of space between students. This means teachers are delivering the same lesson four separate times.

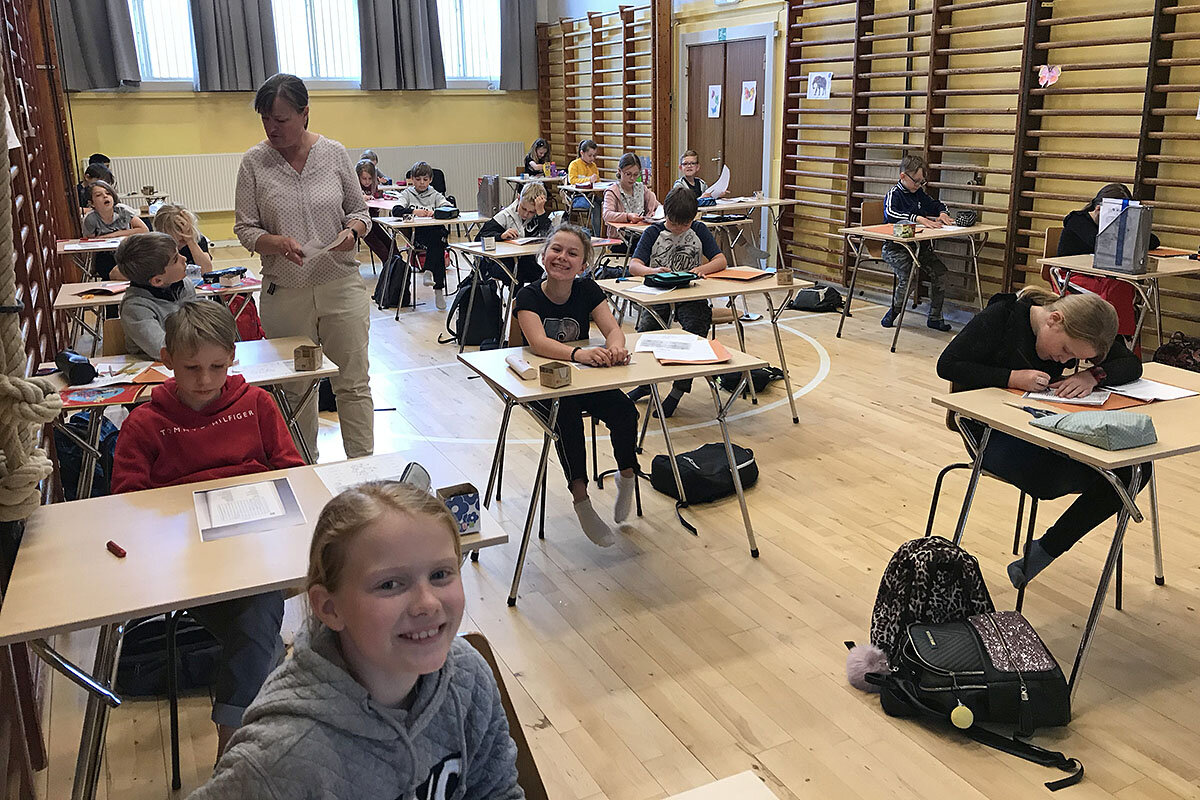

- In Denmark, a tiny country with 1 million primary and secondary students, classes are advised to be held outdoors where possible. Outside Copenhagen, one school is tapping the gym as a classroom, and has staggered recess so equipment can be sanitized between shifts. Public trust in the Danish prime minister surged from 39% to nearly 80% at the end of April.

- In France, a reopening of schools is purely voluntary, as the national government has shifted decision-making power to mayors and principals. Even so, the Education Ministry expects nearly 85% of its schools to reopen in some fashion by May 15.

Countries are weighing a combination of factors that include science, besides elements such as cultural priorities, as they work out the best path forward. “No one knows exactly what’s going to happen,” says François Dubet, a sociologist and professor emeritus of the University of Bordeaux. “If the number of sick people goes down, we’ll return to normal life, but if in 10 days that number goes up, it’s going to get very complicated.”

Germany: Back to school before summer, but no mandates

In Berlin, where schools began reopening in late April, many principals at the city’s 900 mostly public schools are staggering students’ reentry to school. That means some children are coming back for as little as two shifts a week for 150 minutes each time, so that a required 1.5 meters of distance can be maintained between students.

Teachers report excitement to be back on campus, but also a sense of exhaustion, as they’re taking on new duties including acting as “supervisor” to how students move around the building.

“As in, ‘Hey! You can’t stand that close to each other. Don’t walk towards each other! Use that exit, not this one,’” says Lydia Puschnerus, who teaches at a public gymnasium (equivalent to an American secondary school) in the Schöneberg district of Berlin. “It’s worked so far, but over the long term it’s stressful and unnatural.”

Björn Nölte, who teaches at a public school just outside Berlin, says daily routines have completely changed. “There’s always a colleague sitting in front of the bathrooms; there are always colleagues in all of the corridors, to make sure students don’t accidentally get close.”

Disinfectant has been dropped off at schools, and Berlin’s government has granted teachers a one-time payment of €16 ($17) to buy masks. Yet aside from “must follow” hygiene rules, Berlin has been reluctant to issue mandates, letting schools decide how to alter their curriculum, whether to skip exams, and how to stagger classes.

That comes out of the need to serve an incredibly diverse population, with varying degrees of income and digital access, says Ryan Plocher, a Berlin social studies teacher and teacher’s union representative.

“Principals really have to weigh [how to reopen], because schools in richer districts can do the whole thing by distance,” says Mr. Plocher. “But in poorer areas, some students haven’t been in contact with schools at all during the shutdown. Their parents can’t or won’t help, as in, ‘I’m not going to download PDFs over my private data plan.’”

Like the principal in Denmark, administrators at Mr. Plocher’s school have halved class sizes to maintain social distance. They’ve also eliminated or decided to monitor heavily the times that children might be in contact without masks. “That’s toileting, eating, drinking,” says Mr. Plocher, meaning that kids come onto school grounds only for a few hours at a time, with no lunch. Bathroom breaks are taken one student at a time.

Mr. Nölte’s school has subdivided some classes even further, into four units. With the help of co-teachers and supervisors, Mr. Nölte is teaching all four groups of a single German class simultaneously, shuttling between four rooms, which each houses five or six children.

Ultimately, Berlin’s guidelines are flexible enough that some schools – particularly those with enough space to maintain the required distance – could go back to full capacity.

France: A voluntary return

In France, the Ministry of Education has left the decision to open in the hands of local government and school leaders. That’s revolutionary, say experts, in a country where education is “extremely centralized.”

The French education minister expects about 1 million students to return to school, with most of France’s 50,500 schools slated to open in some form. Still, about 10% of towns aren’t expected to reopen schools yet.

“The pandemic is forcing us to decentralize a bit,” says Mr. Dubet. “We’re going to go from a national policy, which is extremely powerful in France, to local policies. This is a new experience for us.”

What is not new, however, is a long-standing familiarity with having to occasionally miss school. In 1968, a social movement led by university students brought the country to a standstill. Earlier this academic year, students of all ages missed class intermittently over the course of about two months due to nationwide strikes against the government’s pension reform plans.

In 1968, no one recorded negative effects of time away in terms of learning gaps, says Mr. Dubet, and most likely no one will now. “The major concern [now] is that students can see their teachers and friends again, that their parents can start working again. Not the education itself.”

For schools opening this week, a 56-page guideline lays out 1 meter (3 feet) of distance between desks and a maximum of 15 students per class. Teachers must wear masks; no ball-playing is allowed. And while preschools and elementary schools open this week, middle schools will follow next week, and high schools at a yet-to-be named date.

Education will look completely different, says Laadja Mamadi, director of a Paris elementary school. “It’s not going to be school as we know it,” says Ms. Mamadi. “We teachers will need to adopt new habits, and so will the students.”

At the 7ème Art public preschool in Paris, for example, teacher Justine Cocquerelle is scanning her classroom to see what needs to be moved, removed, or replaced. Tiny tables host only one miniature chair each; a classroom that usually hosts 25 children will now only take seven at a time, each at his or her own table. Building blocks have been tucked away, and a blanket has been tossed over the books.

“I can’t leave out anything that’s shared between children,” says Ms. Cocquerelle, who returned to school a few days ahead of Thursday’s official reopening. Even the class rabbit, Susie, has been removed from the classroom now that cleaners will be using bleach to disinfect the room at least twice a day. “I’m trying to figure out how I’m going to do this.”

She plans lots of written activities, reading, and singing. Art projects mean individual portions of paint, glue, and tape. Bathroom procedures are still a work in progress, as the four small toilets don’t allow enough distance. What’s clear is that Ms. Cocquerelle will now have double the workload, since she’ll be prepping both in-class activities and online lessons for those who might not return.

“It’s super-complicated,” says Ms. Cocquerelle. “But we hope [the government] sees that it’s working and they open things up a little more.”

France and Denmark have prioritized getting their youngest children back to school. The little ones might be harder to socially distance, they’ve noted, but they need more guidance from an adult, and are still learning social competencies and how to organize work. Plus, young children seem to be less susceptible to serious complications of the coronavirus, and some anecdotal research has suggested that they're less likely to transmit it to adults.

By contrast, other countries like Germany have decided older students should return to schools first, as they’re closer to exams. “That’s not necessarily a pedagogical decision, because tests at the end of ninth grade have been canceled [in Berlin],” says Mr. Plocher, the social studies teacher.

Yet Dr. Karen Wistoft, a Danish education professor, has found that teenagers are feeling more lonely and understimulated during isolation than their younger peers. “The learning potential of teens is so connected to their mental well-being,” she says.

Denmark: Phase 2 of reopening

Back at Marie Mørks School near Copenhagen, Principal Christensen is trying to decide whether a ball is a toy or an “educational tool.”

“If it’s defined as a toy, it has to be wiped down every time it changes hands,” says Mr. Christensen. “But if it is an educational tool, it only has to be cleaned after the school day has ended. The rules are less strict.”

He declared the ball a “tool.” “We have to balance the rules with common sense!” he says.

The Danes are feeling so confident with their reopening strategy that the government announced a second phase of reopening that allows high schoolers to return on May 18. The health authority has also reduced the required social distance in schools from 2 meters to 1.

In Berlin, schools are a few weeks behind Denmark’s reopening, but Mr. Nölte, the teacher at a public school near Berlin, has noticed there’s plenty of joy in coming back together, even in staggered format. “I’ve noticed how happy the students are to see each other,” he says. “Even between my colleagues, I think we will grow closer.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.