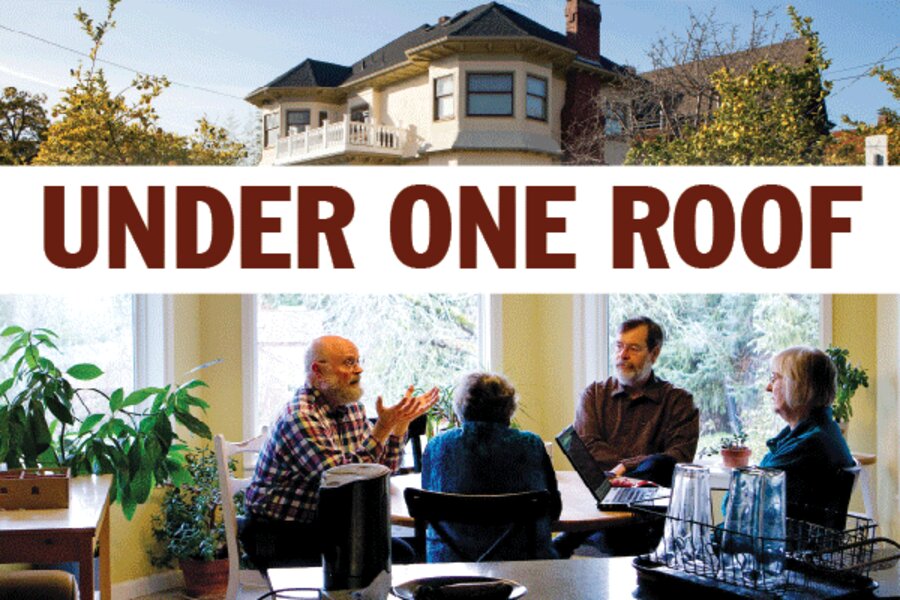

Shared housing: The sharing economy gives roommates a new image

Loading...

| Berkeley, Calif.

Stirring organic lentil soup on the stove, Jay Standish is explaining why there are dozens of sticky notes plastered all over the walls of the Sandbox House, a rented Edwardian mansion just off busy Telegraph Avenue. The Web designer, who cofounded this six-bedroom shared home last summer with a pair of friends, is trying to describe the dynamics of "co-living" when the actual dynamics interrupt him.

Buddha, half Chihuahua, half miniature pinscher, tears through the brightly lit, well-appointed kitchen – which, among other appliances, includes two full-sized refrigerators (one covered with sticky notes) and two electric kettles. Buddha's claws scrabble over polished hardwood as he's pursued by his owner, Aaron Keller, who is in a rush because he's traveling to China later in the evening on business for his startup firm. Moments later, Wall Street dropout-turned-micro-entrepreneur consultant Zac Swartout pops into the kitchen to see who's around.

You might not know it, but this is a slow night in this house occupied by seven high-powered young professionals and one hard-to-catch lap dog. The home's founders, who call themselves "catalysts," describe it as a prototypical platform for shared living, where residents can connect, brainstorm strategies for social and professional enterprises, and even eat and sleep occasionally. It's just another "node" in an expanding network of experimental collaborative-living houses that have sprung up in the San Francisco Bay Area in recent years.

About 50 similar leased, high-end homes in the region now cater to a highly mobile, technologically driven generation of young professionals more interested in networking and peer mentoring than in renting or owning a private home. The sticky notes feathering the walls at Sandbox, Mr. Standish finally gets to explain, tell part of the story: It's as if everyone who lives here wants everyone else to know what's on his or her "to do" list. One note sequence on a wall in the chandeliered dining room is a kind of flowchart aimed at improving meal planning in the house; another note simply asks, "How equalize contribution?"

In general, those selected to live in such houses have diverse interests and backgrounds but share some similar traits, explains Standish. They are smart, ambitious, open to collaboration; interested in both supporting and getting support from each other; and they're not afraid to share the toaster among seven housemates.

And, oh yeah – most of them want to change the world.

Rising interest in shared housing isn't unique to networked Bay Area Millennials hacking conventional housing patterns into a new lifestyle platform that syncs up with their techno-optimism. In states across the nation, including North Carolina, Maryland, Massachusetts, Maine, Pennsylvania, and Washington, the Millennial generation's older, more socially conservative cohorts, including retirement-age baby boomers and their less numerous adult children, known as Generation X, are also experimenting with shared housing arrangements.

Though comprehensive data on the number of unrelated adults who have chosen to live collaboratively doesn't exist, the figure lies somewhere between the 100,000 Americans residing in registered "intentional" communities and the 22 million the US Census Bureau identifies in shared households because of economic reasons.

Officials at the US Department of Housing and Urban Development discount the notion that a significant percentage of Americans would actually want to share homes. "You mean people who run around with their clothes off?" joked one HUD official referring to the stereotype of hippie communes often conjured up by this housing choice.

But a combination of factors is contributing to a gradually growing mutualism in the housing market, other experts say.

"Since the [2007] Great Recession, there has been an increase in shared householding – that's mostly [adult] children moving in with their parents," says Frances Goldscheider, a social demographer at the University of Maryland in College Park. "So, money is a factor." But something else underlies the latent interest in collaborative living, Ms. Goldscheider adds: a growing sense that privacy may be overrated. "Companionship is also a positive," says Goldscheider. "Economists are shocked when you ask them if people want to live together – they think privacy is the only good. But it turns out people actually like to talk."

Though Goldscheider describes the trend in shared housing as "fringe-ish" and cautions that it's too early to say if adult multiresident homes will catch on in the way that condos altered the housing landscape in the 1970s, she notes that there are "underlying trends that make expansion reasonable."

The still-high cost of housing – especially in urban areas such as New York and San Francisco – the sluggish economy, and the steadily rising number of single, unmarried adults in the United States all factor into the 11.4 percent increase in the number of shared households in the country between 2007 and 2010. In addition, Goldscheider says, another trend – the increase in average square footage of homes – makes it easier for those in multimember households to get along without too many arguments over who gets to use the bathroom next.

Earplugs, TP, and cosmonaut parties

"In some ways we're the heirs of the old Berkeley counterculture," says Tony Lai, a lawyer who lives and works in the 7,500-square-foot "SF Embassy" co-living mansion. Located near San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district where the bohemians of the Beat Generation and the hippies of the Summer of Love launched social movements, the Embassy is home to 14 people, including a married couple pioneering a considerably more sumptuous lifestyle than their predecessors.

"Everyone here has their own passion projects, and a lot of it is about social impact," says Mr. Lai, cofounder of an online legal-referral startup called LawGives.com that helps people find legal advice tailored to their needs and budget.

Lai works in the basement at a desk overlooking a full-length bowling alley and lives upstairs in a large, light-filled bedroom with his girlfriend. They pay $2,000 of the $15,000 monthly rent, which includes a room and shared bath, locally sourced food, Wi-Fi, and utilities. The house is decorated with Persian carpets, antiques, and tasteful secondhand furniture, mostly acquired from Craigslist. There's a stocked bar in the English oak-paneled formal dining room, a baby grand piano in the music room, an iPad affixed to the wall in the kitchen, and a sauna/steam room upstairs.

Though shared houses like the Embassy can be pricey, they're very affordable for the Bay Area market and have varied rents for those who share common interests.

In 2010, after a four-year Army stint living cheek by jowl, followed by college and some job hopping, Mike Grace thought the idea of moving into a seven-member shared home called the Rainbow Mansion seemed "a little weird," but the price was right for a small bedroom: $400 per month. Mr. Grace, who had just landed an internship at the NASA Ames Research Center near the Cupertino, Calif., house, soon learned the name came from its address on Rainbow Drive. After he met and liked a few of the house's young residents in science and engineering jobs, he went for it.

Then he found out about the interview: "They called me in and asked me a few questions, like, 'What are you passionate about? What do you want to do with your life? And if you could get only one book out of the library, what would that book be?' " (For the record: "Watchmen" or "The Wealth of Nations.")

Waiting outside while housemates discussed whether he was Rainbow material, he began thinking about how isolated he'd felt living alone in a succession of jobs around the country. Suddenly, the idea of plugging in to a group of people with shared interests in innovation, science, and space, spitballing research strategies over dinner, while splitting rent, utilities, and food bills, seemed to make sense.

Four years later, Grace remains at Rainbow and now occupies a large master suite with a fireplace and private bath. He pays substantially more now ($1,800 per month), but he is earning more after being promoted to a managerial post at Ames. He's engaged, too, to a young mechanical engineer, another Rainbow resident. Grace says the advantages of living in a home where residents are selected based on shared interests, along with a willingness to contribute to the household by doing the dishes, cooking, or ordering toilet paper on Amazon (24 rolls per month) for the house's five bathrooms, far outweigh the drawbacks; for one, there are fewer overall chores because those tasks are shared.

Grace's chores around the house include paying the electric bill and taking out the trash. Buying supplies in bulk, sharing food and cooking duties, and divvying up the other requisite tasks of maintaining a home keep costs down and allow the residents more time to do fun things, he says.

Rainbow residents regularly arrange "salons" with guest speakers; they also hike together at a nearby wildlife preserve. Upcoming events at the house include a presentation by a Kickstarter-funded Japanese group adapting ink-jet printer technology to produce electronic circuits. Housemates throw an annual "Yuri Gagarin Party" in honor of the Russian cosmonaut, the first human to journey into outer space.

Despite the stellar benefits, co-living has a few downsides, Grace and others say. Living inside the physical manifestation of a social network is a bit different from scrolling through one online, where obnoxious content can be managed with the delete button.

At Rainbow, group decisions have resulted in ejecting residents for drinking problems, abusive arguments between couples, and failure to pay rent. Some have left on their own for everything from discovering they didn't like sharing a refrigerator with six other people to mistakenly thinking they could acquire venture capital from housemates for their startups.

But it was the noise that got to Grace in the beginning: "I had to get earplugs to sleep. When that didn't work, I wrapped a T-shirt around my head." Eventually, he became used to the feedback loop of constant conversation, late-night music, and laughter filling the halls. Grace says he and his fiancée will continue living in Rainbow after they marry, though he harbors dreams of developing a new affordable cooperative residence adapted for couples with children.

"We still have that sense in America that you're not a real adult until you own your own house, but that has consequences," including a diminished sense of community, Grace says.

Shared housing for grown-ups

In other parts of the country, adults who still view the old-fashioned mortgage as a good way to save, build credit, and invest have taken co-living a step further. Instead of renting in a collaborative house full of people coming and going, they ask, for folks serious about building connections and community, why not put down some roots and purchase a home together?

It might even save your life, says one advocate of mortgage-based shared living.

Craig "Oz" Ragland was upstairs in his office at the Craftsman-style home he and his wife own with four other families in Bothell, Wash., when he heard a housemate, Marilyn Hanna-Myrick, screaming for help downstairs.

Bolting down the steps, Mr. Ragland found Ms. Hanna-Myrick's husband, Chuck, a retired engineer, clutching at his throat. Ragland quickly realized his housemate was choking and performed the Heimlich maneuver, dislodging an apple chunk from his throat with a few firm thrusts to his abdomen.

The Hanna-Myricks bought a share of the 4,000-square-foot home in the Songaia cohousing development with the Raglands and three other families in 2010 after selling their own house in the same community. (The house is occupied by two of the investor families and a renter; the three remaining mortgage holders live in other houses in the development.) The 20-year-old multigenerational development includes 13 single-family homes, and residents share child care, cars, and 11 acres of land.

"It's easy to think about it primarily from an economic point of view, but there are social, environmental, and other benefits," Ragland says of the benefits of what he calls "cohouseholding." "Look, I saved a housemate's life."

Ragland, a retired Microsoft executive, founded The Cohouseholding Project, a research and advocacy organization that helps educate and connect adults interested in learning more about shared mortgages, promoting collaborative living among a slightly more mature age group who lean more toward the stability and security of homeownership than the more nomadic, rent-oriented Millennials.

The $680,000 house, purchased outright by the group with legal expertise from a real estate attorney, "was outside the range that any one of the co-owners could afford [alone], yet each of us have an abundance of space," Ragland says, noting that he and his wife have a "huge" bedroom and private bathroom, separate in-home offices, and an art studio. Other occupants have their own bedrooms and bathrooms, while extra spaces in the house – the kitchen, living and dining areas, and yards – are maintained by all residents.

The US Census Bureau doesn't have a survey question, yet, that asks homeowners whether they share mortgages, so the number doing so nationwide is unknown, and Ragland has just started trying to track that information.

Nevertheless, more examples of shared ownership houses for adults are beginning to crop up around the country. One trio of retired couples in Maine hired architect Richard Renner to design an unusual home for them on the edge of a salt marsh just outside Portland, with the goal of enabling the couples to co-own and live together while maintaining plenty of privacy. The complex of three interconnected spaces was completed and occupied in 2011. Though one of the residents has since died unexpectedly, the others remain together.

The couples had vacationed together annually in a shared beach house, and their desire to live together "grew out of their strong emotional bond," Mr. Renner explains. "They felt that the synergy between them, and being together, would generate a richer life than if they were alone."

Renner's architectural task was to create as many opportunities for chance encounters as possible while reducing the carbon footprint; the residents had a goal of zero net energy consumption (creating as much energy as used). They share an entrance, parking, and a single wood-pellet boiler for all the units, and solar panels for electricity. There is a common exercise area, movie-watching space, and gathering room, and an extra, unoccupied unit in case anyone requires on-site assistance or medical care.

The Maine project shows that even deep-pocketed, design-conscious people in the US are becoming interested in the notion of sharing living space with unrelated adults at home. Renner says: "There's a different model [emerging]. We're finding other clients are thinking about it, and at some point, I'll think about it – about not wanting to grow old in isolation or in an institutional setting. How do you age gracefully in place?"

It helps if you don't give away your housemates' stuff.

Misadventure: the Batman matchbook bust

Just ask Louise Machinist, one of three Pennsylvania women to whom Ragland often directs inquiries about how to set up a shared mortgage household. Ms. Machinist and her housemates co-wrote a book on how to set up and happily coexist in a shared household: "My House, Our House: Living Far Better for Far Less in a Cooperative Household."

Machinist bought a four-story brick Colonial in Pittsburgh back in 2004 with Karen Bush and Jean McQuillin, each of whom once owned their own homes and were approaching retirement age. When the three divorced, partially retired women decided to join forces, sell their homes, and buy one together for reasons of companionship, support, and affordability, one of their first difficult tasks was how to merge three separate households. Some things just had to go, like the extra jars of paprika. But the women reached an agreement that no one would offload anyone else's stuff without permission.

The system seemed to be working well until Machinist was lighting candles at a service at her Unitarian Church and noticed an unusual Batman matchbook autographed by the actor Adam West – just like the one in the collection of matchbooks she and her ex-husband had. In fact, she realized, it was hers.

"It wasn't something I was that attached to, but it was like, 'Aha! I've nailed them!' " Machinist says with mock indignation. "And I said: 'What are you guys doing giving away my stuff?' But there really wasn't any controversy. They had been in a crumpled paper bag and someone must have said, 'Who needs a hundred old matchbooks?' and started giving them out. It's just an example of the kind of mishaps that can happen."

The housemates long ago laughed off the matchbook episode, though they cite it as an example of how important it is not to sweat the small stuff when sharing a home. Besides, they have bigger fish to fry; Machinist, Ms. Bush, and Ms. McQuillin have found themselves riding what Bush described as a rising "wave" of interest in shared housing for active adults.

Since June of last year, their book has sold 1,000 copies; they have about 100 daily visitors to their website, myhouseourhouse.com, and hundreds of Twitter followers and Facebook likes. The women's project was featured on NBC's "Today" show, in November, where they discussed the practical, legal, and financial aspects of splitting ownership of a mortgage and sharing a home.

Just as the Millennials are doing, baby boomers are beginning to build infrastructure online to help those interested in shared housing connect. The three Pittsburgh women are part of a budding, nationwide nonprofit network of organizations and experts on collaborative housing in states including Minnesota, California, and Connecticut. The goal is to promote awareness and expand options for multigenerational shared housing. Called Golden Girls Homes, the start-up is holding weekly conference calls and plans to launch its first online newsletter in May and establish regional offices across the US within three years. (Despite the name, which is likely to change, men's involvement is welcome and anticipated, says Bonnie Moore, of Bowie, Md., who is coordinating the burgeoning network.)

Ms. Moore, an attorney and management consultant, launched a shared home with three other active adult women in her large, Levitt-style home in suburban Maryland a few years ago, and runs her own independent matching services for adults interested in co-living, which will be merged into the nationwide network.

Speaking from Sarasota, Fla., last month, where she was presenting information at an alternative housing conference for seniors, Bush summarized the three women's reasons for moving in together: "We looked at the social benefits of it, the environmental benefits in terms of reduction of energy consumption, intellectual engagement, health, support, the financial benefits, and we said, 'Why don't we just do this now? What are we waiting for?' "

The women estimate that they used to spend a combined annual total of $9,000 on utilities for their homes; whereas, after moving under the same roof in 2005, they spent a combined total of $5,332, almost a 50 percent savings. With numbers like that, the women are happy to take turns using the washer and dryer.

'Curated' living; not just random roomies

The economic and resource reduction advantages of collaborative living are a big draw. But they alone don't account for the choices of people like Jedediah Berry, a successful mid-career professional with a regular paycheck. A novelist and professor at Bard College in New York, Mr. Berry could well afford a place of his own, yet he prefers to live in what he describes as an informally "curated" shared home with other adults in Amherst, Mass.

He was on the verge last year of purchasing a single-family home in Greenfield, Mass., near where his writer-librarian girlfriend, Emily Houk, works. But he changed his mind when the opportunity arose to rent a small suite (including bath and office) in a six-bedroom Victorian house known as a locus for educators, artists, musicians, and others working in local farming ventures.

"It was a conscious choice," not just a matter of money, Berry says about moving with Ms. Houk into the house shared by six other young adults. "We both saw in it an opportunity to have a simple kind of existence, by having people who we know and trust and with whom we can collaboratively maintain the space, and be close to our friends, and, in Emily's case, her work. So we're able to live affordably and in such a way that our energies are focused on our connections to this area, and the people, and also to our own creative work."

Neal Gorenflo, a former stock market analyst who cofounded Shareable.net, an online magazine, calls nascent multigenerational innovation in collaborative housing a "paradigm shift.... The bigger picture is we're moving from a top-down, factory-model society to a networked, peer-to-peer model. It's a transformation that's been under way for a while, but now it's hitting Main Street. At the same time, you have a myriad of new technology and models for doing things that allow the individual to route around old institutions," Mr. Gorenflo says.

"Housing is a perfect example," he adds. "It is the No. 1 household expense, and a lot of people just can't afford it anymore. The old American dream didn't work out for them."

While Berry refers to his eight-resident home in Massachusetts as an "unintentional" community because its occupants are laid back about organized activities, avoiding meetings and chore charts in favor of spontaneous self-initiative (say for sweeping floors, shoveling snow, maintaining the pellet stove, or arranging a dinner party/ukulele jam), the co-living houses out West are more directed and purposeful.

Each house has its own website and online bookings and application system, for example, and group meetings, events, and dinners are scheduled regularly. There's a reason for the extra effort: Cofounders and residents of some of these houses – including Standish, the soupmaking Sandbox resident who has an MBA in sustainable business, and his Millennial partners Ben Provan, another Sandbox resident who has a degree in mechanical engineering, and Jessy Schingler, a former NASA programmer – are writing the code for a prototypical shared housing domain they hope will go viral.

"We are looking at it within the context of open source, modern collaborative lifestyles, and we think there is a significant market for this kind of hybrid housing," says Ms. Schingler, of the Embassy in San Francisco.

Schingler is actively working on branding and extending the reach of the Embassy Network – affiliated co-living houses are now online in Indonesia, Guatemala, Japan, Italy, and Hawaii – while coordinating with Standish and Mr. Provan on other shared housing ventures in the Bay Area. The trio recently raised $68,000 in capital to lease and launch another co-living Victorian in Berkeley, called The Farmhouse, with 16 bedrooms (opening April 1). And they have landed a consulting contract working with architects and developers on a 230-unit, new construction co-living complex on Harrison Street in San Francisco. Part of the consultancy involves a just-launched online census of co-living homes around the country.

As Gorenflo puts it, Schingler and other shared housing advocates are "consciously hacking housing ... trying to improve the housing system by reconfiguring it and making it better so that it works for them. It's an engineering mind-set being used on a social issue."

Inside the stately Embassy house on a recent weeknight, eight residents gathered after work around the kitchen island and, while munching on salted macadamia nuts and tortilla chips with hummus, talked about the growing everyday use of robots. As some began drifting upstairs for the night, Eric Rogers, a visiting Yale School of Architecture student, tidied up the kitchen counter and broached another topic of discussion: whether America's suburbs might someday become ghettos.

Clues to their thinking on that question are evident over in the parlor, behind glass-encased bookshelves, where well-thumbed tomes included "Plan B 3.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization" and "How Many People Can the Earth Support?" and, seemingly incongruously, "How to Build a Real Estate Empire."

"The cool thing about living here is that it's one node in a network," Mr. Rogers had said during an earlier conversation in the dining room. "I'm starting one in New Hampshire soon."