Shakespeare’s plays meet plagiarism-detection software

Loading...

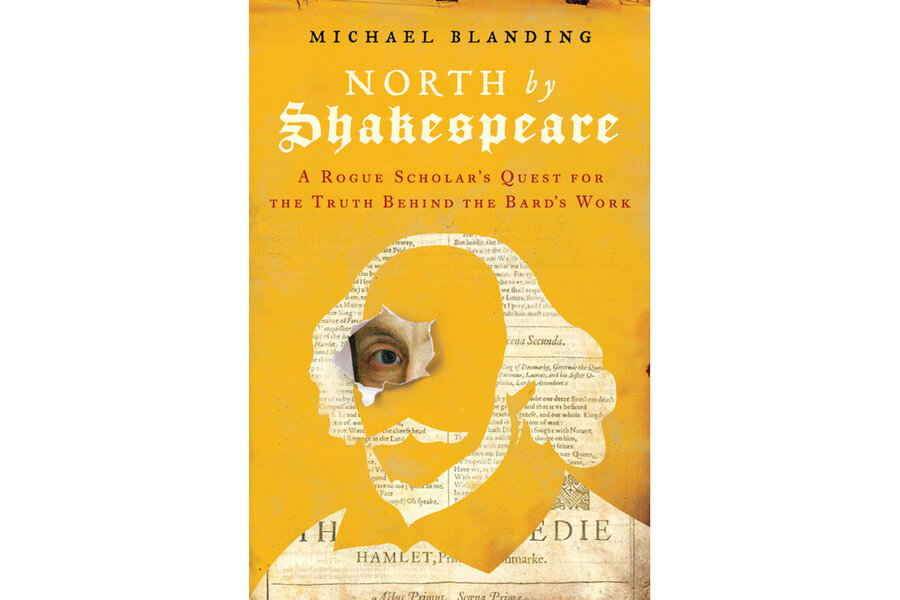

The “rogue scholar” referred to in Michael Blandings’ captivating book, “North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work,” is a researcher who has confronted one of the most entrenched literary orthodoxies: that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays that bear his name.

Dennis McCarthy, an amateur independent researcher, is hardly the first to challenge that orthodoxy, of course. For well over a century, iconoclasts of all stripes, including such public figures as Sigmund Freud, Helen Keller, Henry James (who came to think that “the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world”), and of course Mark Twain, whose little 1909 book “Is Shakespeare Dead?” still makes hugely entertaining reading.

As Blanding relates, McCarthy’s approach to this vexing question centers on Elizabethan courtier and famed Plutarch translator Sir Thomas North. McCarthy’s innovation isn’t to contend that North actually wrote the plays that bear Shakespeare’s name; instead, he argues that Shakespeare wrote the plays by plagiarizing liberally from North’s earlier works, some of which were published and are now lost.

Years ago, McCarthy impulsively self-published a book outlining some of his earliest thoughts on the subject. He called it “North of Shakespeare,” and in a neat gesture of writerly magnanimity, Blanding adapts that title in order to tell the story of McCarthy’s journey, North’s adventures, and, ultimately, the whole Shakespeare authorship question.

How on Earth could the man from Stratford, with his apparently limited education and experience, possibly be the author of the plays of Shakespeare, which bristle with higher learning and echo with an enormous range of exotic life-experiences? Traditionally, as Blanding points out, experts have looked to Shakespeare’s “lost years” between 1585 and 1592. “Scholars have tried to stuff everything Shakespeare could possibly need for his plays into this period,” he writes, “conjecturing that he traveled in Italy, fought in wars in Flanders, or even sailed to America.” But still the gap between the man and the works remains.

This disconnect has led generations of doubters to conclude that Shakespeare didn’t write the plays – and to put forward all kinds of candidates for who did.

As Blanding makes clear, McCarthy is side-stepping that approach – and, he hopes, most of the instant dismissal it tends to provoke. He employed an open-source plagiarism detection software called WCopyfind in order to compare the writings of Thomas North and Shakespeare, looking for identical word choices, combinations, and phrasings. The computer screen “came alive” with thousands of common phrases, Blanding writes. “I couldn’t believe it,” McCarthy told him. “It lights up all over the screen.”

Blanding dramatizes very effectively the thrill of this literary investigation, giving readers a revelation-by-revelation account of the developments in McCarthy’s thinking without ever drowning them in trivia. The book likewise does a virtuoso job of evoking both the realities of Shakespeare’s world and the twists and turns of the whole Shakespeare question.

If, in addition to his poems and translations, Thomas North wrote a raft of plays rooted in his own reading and experiences, and if Shakespeare then used those works to write his own plays, then both McCarthy’s obscure original and this account by the bestselling journalist Blanding – is the most elegant proposed solution to the authorship question to appear in many decades.

It will still ruffle feathers, particularly scholarly feathers. But Blanding urges readers to remember that collaboration and plagiarism were the rule rather than the exception in Elizabethan England. Quite apart from the compelling case made through plagiarism detection software, Blanding and McCarthy assert that it would have been something of a miracle if Shakespeare didn’t collaborate and plagiarize as often as the market demanded.

“North by Shakespeare” gives a curiously invigorating glimpse of that jobbing, hustling Shakespeare, a business-minded theater man with an eye for the main chance, somebody who freely borrowed good lines from other writers (something Robert Greene famously noted as early as 1592) and wouldn’t have hesitated to mine a trove of plays that drew on the kind of wide and wild life he himself didn’t lead.

“If Shakespeare had originated the canon rather than adapted it, it would be about the people he met in Stratford, and contemporary London events, which there were plays on during the period,” says McCarthy, whereas that’s not what’s in the Shakespeare canon, which consists instead of event after event from the life of Thomas North, who McCarthy describes as “one of the most autobiographical writers there is.”

Does “North by Shakespeare” finally settle the Shakespeare authorship question? It’s unlikely anything ever will – that’s the nature of orthodoxies. But this isn’t some silly conspiracy theory. Orthodox scholars who simply ignore it do so at the peril of their reputations.