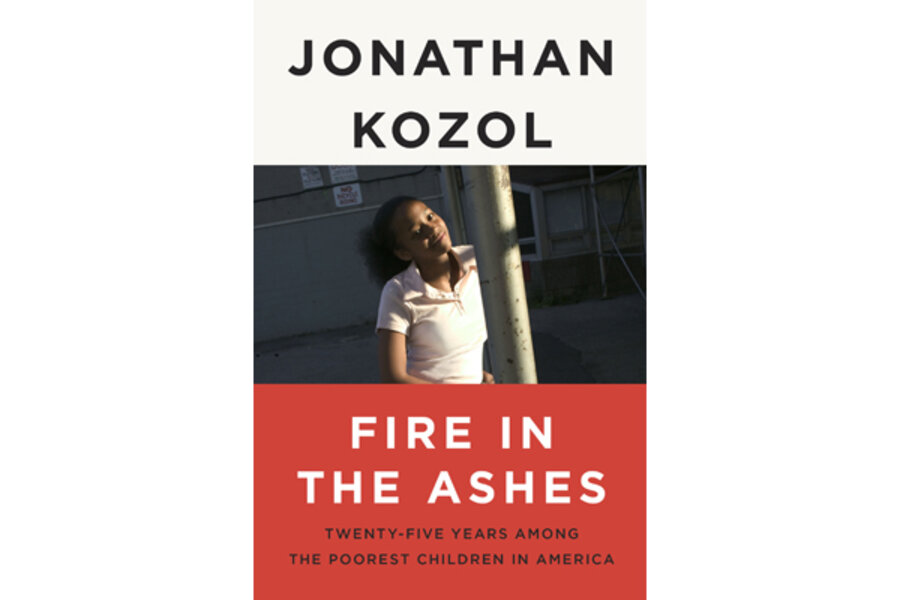

Fire in the Ashes

Loading...

Reading Jonathan Kozol’s latest book is discomfiting – as if you are peering into a joyous family reunion and mournful memorial at the same time.

Fire in the Ashes: Twenty-Five Years Among the Poorest Children in America chronicles what became of some the families Kozol first met in New York City’s homeless shelters and deeply impoverished neighborhoods starting in the mid-1980s.

It’s not a sociological exercise, nor is it tied up neatly into a bundle that lends itself to overt political commentary, such as his previous indictments of the rampant inequality in education.

It’s a deeply personal collection of stories about people who became his friends – stories in which the ashes are sometimes so deep it can be hard to find the fire. But that’s right where Kozol’s storytelling gifts shine through: with simple anecdotes that show the soulful humor, compassion, and wisdom that kindles progress among the survivors.

Kozol met many of the children at the Martinique Hotel, a shelter for homeless families. One mother described it to Kozol as “'a cesspool… "Traumatizing" is too nice and too genteel.'” Beyond being overcrowded and decrepit, it was a place where women were coerced by inspectors to give sexual favors, a place where children were raped in dark corners.

Christopher was 10, staying with his parents and two younger siblings at the Martinique, when Kozol first met him. “I saw that look of hunger in his eyes,” Kozol writes. “I saw him running out in traffic when the cars slowed down on Broadway, hoping for a couple dollars to be handed through a window…. [He’d] seen the needle-users buying what they needed in the hallways.”

After being in and out of prison, Christopher eventually died from a drug overdose. He was one of three boys Kozol writes about who went on to early deaths – one from suicide, one from “surfing” on top of trains.

Despite the best efforts of family members – in two cases, older sisters who went on to more stable lives – the harshness of the boys’ childhood surroundings seem to have been insurmountable.

But then there are the stories of the fighters and survivors.

Alice Washington was in her forties when Kozol met her at the Martinique. She fought unsuccessfully the city’s plans to relocate her and other families to the poorest of poor neighborhoods in the Bronx.

Alice relished life’s absurdities, Kozol notes. On a steamy day, she showed him a New York Times story about how the heat had been uncomfortable for the carriage horses. “’It wasn’t much of a week to be a horse...,’ the paper said. ‘People, at least, have air-conditioning and friends with pools.'...Her reaction... was less bitter than resigned. ‘I guess that puts me with the horses,’ she said quietly.”

She became a nurturing friend to Kozol and has since passed away due to illness. Kozol remembers her as someone who “rejected victimhood,” someone who rose above the bitterness that surrounded her.

The children who rose above have incredible reservoirs of perseverance. But they also have incredible supporters –- a whole church congregation in Montana that invites a family to relocate to their town; a benefactor who agrees to pay for private school; and Martha, a woman whose advocacy for the children in her midst goes way beyond her role as minister in a Bronx church.

Longtime Kozol readers will be delighted to see the return of “Pineapple," the little girl who didn’t hesitate to tell Kozol his suit was too worn out and he should buy a new one.

Kozol first met her as a kindergartener in a school that “was almost always in a state of chaos because so many teachers did not stay for long.” For middle school and high school, Martha helped her get scholarships to private schools in Manhattan and Rhode Island. The daughter of Spanish-speaking immigrants, she had to work hard to overcome deficits in reading, writing, and basic study skills, but her older sister and she both finished high school (firsts in their family) and went on to college.

Pineapple studied to be a social worker, to equip herself to help the next generation of children who have to swim against the current.

As a young woman, she talked with Kozol for the first time about shootings in her public-housing neighborhood when she was a child. “’I didn’t know when I was ten that it wasn’t like this for most other children,’” she told him. “’Now... [I] understand there needs to be a whole lot of improvement. But for that to happen... the entire attitude of white superiority would have to be attacked. You would have to start again from scratch.’”

Kozol saw Pineapple in a new light: “There was an assertiveness and sharpness in her choice of words... The bluntness that was very much a part of her delightful personality when she was a little girl, as in her criticism of the clothes I wore, had by no means disappeared, but it was directed more and more to matters that went far beyond her own amusements and concerns.”

Maybe when Kozol is ready to retire, Pineapple can pick up where he leaves off – chronicling the ashes of injustice -- and the flames that give rise to the phoenix in children like herself.

Stacy Teicher Khadaroo is a national news reporter for the Christian Science Monitor.