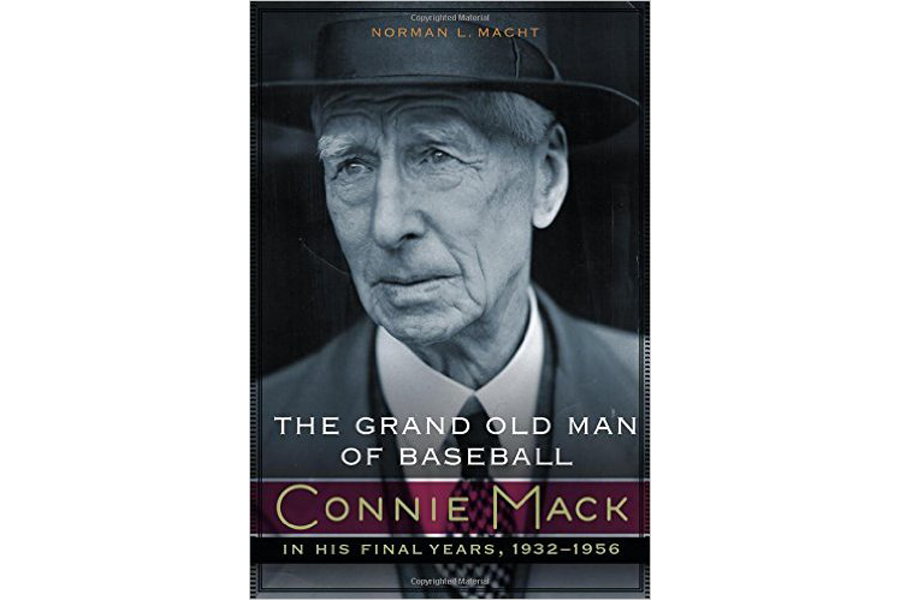

If ever a baseball book could be called a definitive biography, this examination of Connie Mack can. Actually it is the third installment of a trilogy that begins in the late 1800s and runs until Mack’s death in 1956, covering his years as a player, player-manager, manager, and team owner. This installment alone runs more than 600 pages with a 30-page index, which, if excessive, reflects the fact that Mack’s story is partly that of the major leagues during the first half of the 20th century. He managed the Philadelphia Athletics, who moved to Kansas City and Oakland after his death, during the first 50 years of the team’s existence. By his retirement and the end of the1950 season, he pretty much had experienced it all, managing in a record 7,755 games, leading the franchise to five World Series championships and 17 last-place finishes.

The on-field and financial struggles of the A’s, as well as those Mack dealt with during his sunset years in the game, receive a full exploration by Norman Macht, a member of the Society for American Baseball Research.

Here’s an excerpt from Connie Mack:

“Connie Mack was an anachronism to the new generation of ballplayers. Those young enough to be his great-grandsons could do nothing but stare at the sight of the tall, thin old man wearing a dark business suit in the A’s dugout. Jerry Witte, a thirty-year-old rookie with the Browns, said the first time he saw Connie Mack in Sportsman’s Park, it was like ‘staring at a statue that moved from one ballpark to another.’

“Gene Woodling was a rookie outfielder with the Indians. Fifty years later the picture of Mr. Mack entering the A’s dugout remained vivid in his memory: ‘He usually appeared during infield practice about ten minutes before game time.We’d be looking for him and when he came in everything sort of stopped. In our dugout we all stood up. It was the same when I went to the Yankees, for as long as he managed. It was a sign of respect, and one of the nicest things I ever saw in baseball.'”