Olympics: Why it's bye bye birdie for badminton in Indonesia

Loading...

| Jakarta, Indonesia

Indonesia has called for a review of this year’s Olympic badminton format after the country’s hopes for Olympic glory were damaged after the Badminton World Federation decided to toss a pair of its female doubles players from the competition.

The Indonesians were among four females doubles pairs disqualified from the 2012 Games on Wednesday for trying to lose their pool play match so they could face an easier opponent in the quarterfinals.

The teams – two from South Korea and one each from China and Indonesia – were punished for “not using one’s best efforts to win a match” and “conducting oneself in a manner that is clearly abusive or detrimental to the sport.”

All four pairs had already qualified for the quarterfinals, but had to finish pool play to determine seeding for the elimination bracket. None wanted to play the second-ranked Chinese female doubles team any sooner in the elimination round than they had too.

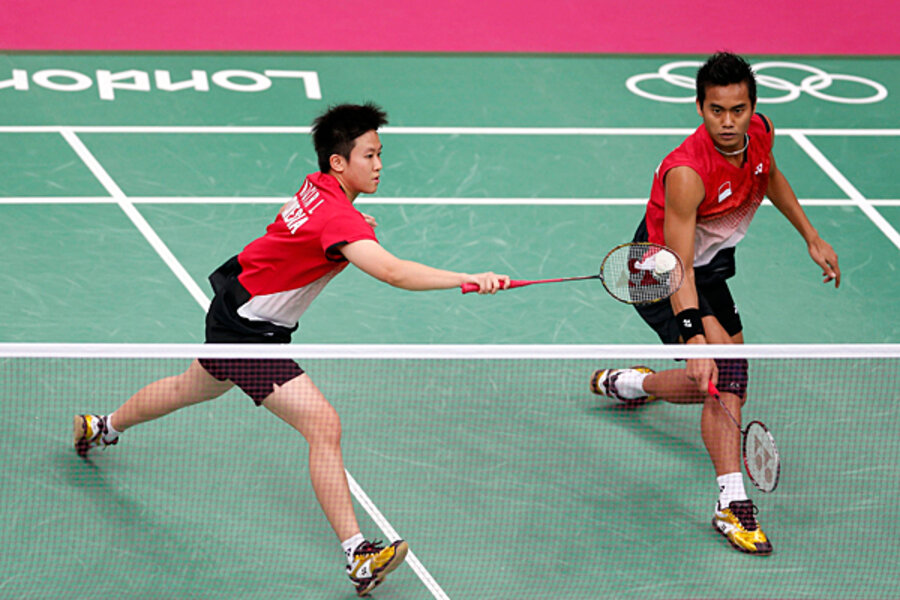

Greysia Polii and Meilana Jauhari, the Indonesian pair, admitted to throwing their game against South Korea on Wednesday. Some Indonesian shuttlers said "tanking," as it's known, has become common in the game, because of the structure of badminton tournaments.

“I think we must blame the system because it allows the players to do this,” says Alan Budikusumo, a former Olympic champion who won gold in the men’s singles at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. He says the players were wrong but that he understands the pressure placed on them to win medals in a sport second only in popularity to soccer here.

Fading game

Badminton is Indonesia's national sport, and the only one it consistently brings home Olympic medals for. The country has won gold for badminton in every Olympic games since the sport was first introduced on 1992.

Although Polii and Jauhari were not among the country's top-ranked players, their ousting reduces Indonesia’s chances of medaling in badminton, particularly after past champion Taufik Hidayat bowed out following a loss to China’s Lin Dan in the men’s singles.

Some say their disqualification is also likely to heap some shame on a sport that already faces waning public and government support. “This is very bad for us,” says Budikusumo. “We must do much better than this to develop better than before.”

When he returned from the 1992 Olympic games, medal in hand, Budikusumo was paraded around town and feted as a national hero. Today young players have fewer incentives to take up the sport, he says.

Unlike other countries, where Olympians receive big cash prizes from their governments, Indonesian athletes are often left to fend for themselves, says Budikusumo. Without the right sweeteners, fewer people are taking up the game.

Officials here admit that the country has put more money and resources into preparing athletes for regional competitions, such as the Southeast Asian Games, which involves a host of non-Olympic sports including petanque and pencak silat, an Indonesian martial art.

With prospects for a future after the Olympics fairly low, some badminton champs have gone on to try their luck in other countries. Former gold-medal champion Tony Gunawan moved to the United States and started training young players there.

Despite his age, 37, he partnered with Howard Bach for the US badminton men’s doubles. The team crashed early in the Games, doing little to meet Gunawan’s hopes of stoking more global interest in badminton.

Tanking common

Match throwing is nothing new to badminton, which has created its share of controversies during its 20 year Olympic run. Heated internal politics have drawn quiet warnings in the past from the International Olympic Committee, according to AFP.

This year the Olympics moved away from a straight knock-out system to a pool play round for qualification for the elimination bracket. The approach creates perverse incentives for players, since in certain circumstances their chances of winning a medal improves if they throw a pool play match. Basically, the disqualified players have been punished for using a little game theory.

Badminton is far from the only sport where tanking happens. In the NBA, teams with no hope of making the playoffs are frequently accused of tanking games towards the end of the year, since teams with the weakest records get higher picks in the following year's draft. Soccer tournaments often turn on pool play matches where one team is indifferent to victory, since it's already qualified for the next round, and rests its best players.

In 1998's TIger Cup played in Vietnam, Indonesia was embroiled in one of soccer's great match throwing scandals. The winner of the Thailand-Indonesia pool play match would have to face Vietnam in front of its rabid home fans, so both teams spent the first 85 minutes or so trying to lose. With the score tied in the dying moments of regulation, Indonesia began attacking its own goal, with the Thai players desperately defending. Indonesia succeeded in scoring the own goal, then went on to be crushed by Singapore in the following round before being sanctioned by FIFA.

For badminton, Indonesia’s top sports official said the format was the main problem.

“We respect the Badminton World Federation’s decision but we want the BWF to review the competition system they used,” said Indonesia’s Sports and Youth Minister Andi Mallarangeng in a statement posted on the Indonesian Badminton Association’s website.

Meanwhile, the disqualification drew a fairly muted response here in Indonesia.

Some fans said they were embarrassed and lashed out at the players for not being brave enough to face up to a tough opponent. “Why are we so afraid of China,” one Twitter user wrote. “We [were] once the greatest in badminton.”

Erick Thohir, the head of Indonesia’s Olympic team, used the social media site first to point the finger at China for frequently throwing games without sanction, and then to ask fans to give their moral support to Indonesian athletes who remained in the competition.

But while the news hit Twitter feeds and Facebook pages, it didn't make it to the front pages of the nation's major papers.

Some sports commentators called the dispute “shameful,” describing players who served the shuttlecock into the net and barely made an effort to keep a rally going for more than four shots. The performance drew widespread boos and hoots from a packed stadium.

“Who wants to sit through something like that,” said Laurent Constantin, a men’s doubles player from France.

Laurencia Averina, Budikusumo’s daughter, came to her country’s defense.

“Usually we play to win, not to lose,” said she. The 13-year-old has been playing badminton since the age of four, but while she says she loves the sport, she also says she has no plans to go to the Olympics.