Spiritual journey revival: Hajj returns to Mecca in force

Loading...

| Mecca, Saudi Arabia

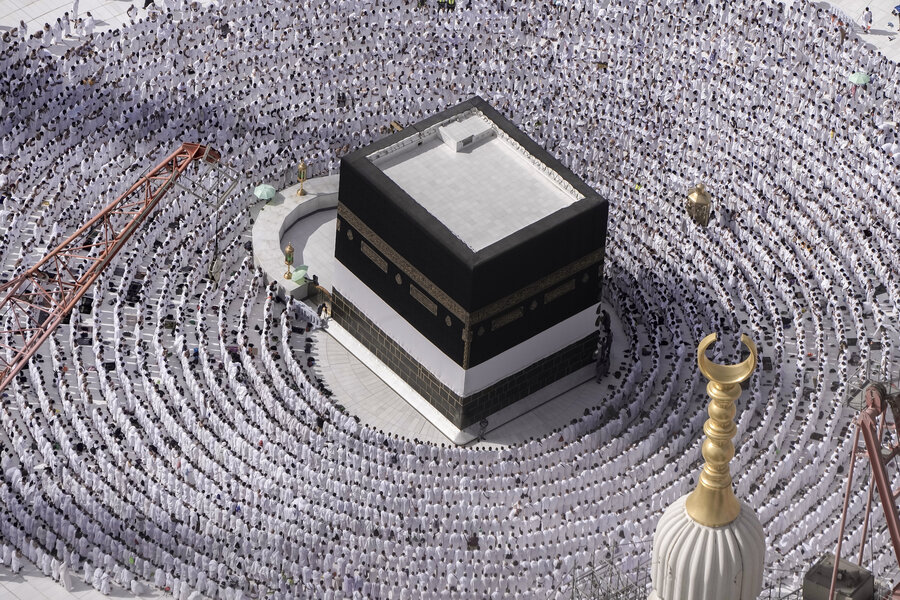

Over 2 million Muslims will take part in this week’s Hajj pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia, as one of the world’s largest religious gatherings returns to full capacity following years of coronavirus restrictions.

The Hajj is one of the five pillars of Islam, and all Muslims are required to undertake it at least once in their lives if they are physically and financially able to do so. For the pilgrims, it is a profound spiritual experience that wipes away sins, brings them closer to God and highlights Muslim unity.

For the Saudi royal family, which captured Mecca in the 1920s, organizing the pilgrimage is a major source of pride and legitimacy. Authorities have invested billions of dollars in modern infrastructure, but the Hajj has occasionally been marred by tragedy, as in 2015, when over 2,400 pilgrims died in a stampede.

Here’s a look at the pilgrimage, which begins on Monday, and its meaning.

What is the history of the Hajj pilgrimage in Islam?

The pilgrimage draws Muslims from around the world to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia, where they walk in the footsteps of the Prophet Muhammad and retrace the journey of Ibrahim and Ismail, or Abraham and Ishmael as they are known in the Christian and Jewish traditions.

As related in the Quran, Ibrahim is called upon to sacrifice his son Ismail as a test of faith, but God stays his hand at the last moment. Ibrahim and Ismail later are said to have built the Kaaba together. In the Christian and Jewish traditions, Abraham nearly sacrifices his other son, Isaac, on Mount Moriah, which is associated with a major holy site in Jerusalem.

The Kaaba was a center for polytheistic worship among pagan Arabs until the arrival of Islam in the 7th century, when the Prophet Muhammad consecrated the site and inaugurated the Hajj.

Muslims do not worship the Kaaba, a cube-shaped structure covered in a black, gold-embroidered cloth, but view it as their most sacred place and a powerful symbol of unity and monotheism. No matter where they are in the world, Muslims face toward the Kaaba during their daily prayers.

The Hajj has been held every year since the time of the prophet, even through wars, plagues, and other turmoil.

In the Middle Ages, Muslim rulers organized massive caravans with armed escorts that would depart from Cairo, Damascus and other cities. It was an arduous journey through deserts where Bedouin tribes carried out raids and demanded tribute. A notorious Bedouin raid in 1757 wiped out an entire Hajj caravan, killing thousands of pilgrims.

In 2020, amid worldwide coronavirus lockdowns, Saudi Arabia limited the pilgrimage to a few thousand citizens and local residents. This is the first year it returns to full capacity.

How do Muslims prepare for the Hajj?

Some pilgrims spend their whole lives saving up for the journey or wait years before getting a permit, which Saudi authorities distribute to countries based on a quota system. Travel agents offer packages catering to all income levels, and charities assist needy pilgrims.

Pilgrims begin by entering a state of spiritual purity known as “ihram.” Women forgo make-up and perfume and cover their hair, while men change into seamless terrycloth robes. The garments cannot contain any stitching, a rule intended to promote unity among the rich and poor.

Pilgrims are forbidden from cutting their hair, trimming their nails, or engaging in sexual intercourse while in the state of ihram. They are not supposed to argue or fight, but the heat, crowds, and difficulty of the journey inevitably test people’s patience.

Many Muslims visit Medina, where the Prophet Muhammad is buried and where he built the first mosque, before heading to Mecca.

What happens during the Hajj?

The Hajj begins with Muslims circling the Kaaba in Mecca counter-clockwise seven times while reciting prayers. Then they walk between two hills in a reenactment of Hagar’s search for water for her son, Ismail, a story that occurs in different forms in Muslim, Christian, and Jewish traditions.

All of this takes place inside Mecca’s Grand Mosque – the world’s largest – which encompasses the Kaaba and the two hills.

The next day, pilgrims head to Mount Arafat, some 20 kilometers (12 miles) east of Mecca, where the Prophet Muhammad delivered his final sermon. Here, they stand in prayer throughout the day asking God for forgiveness of their sins in what many view as the spiritual high point of the pilgrimage.

Around sunset, pilgrims walk or take buses to an area called Muzdalifa, 9 kilometers (5.5 miles) west of Arafat. They pick up pebbles to use the next day in a symbolic stoning of the devil in the valley of Mina, where Muslims believe Ibrahim was tempted to ignore God’s command to sacrifice his son. The pilgrims stay for several nights in Mina in one of the largest tent camps in the world.

The pilgrimage ends with a final circling of the Kaaba and further casting of stones at Mina. Men often shave their heads and women clip a lock of hair, signaling renewal. Many will assume the title of “hajj” or “hajja” – a great honor, particularly in more traditional communities. Some paint murals on their homes with images of airplanes, ships, and the Kaaba to commemorate the journey.

The final days of Hajj coincide with Eid al-Adha, or the festival of sacrifice, a joyous occasion celebrated by Muslims around the world to commemorate Ibrahim’s test of faith. During the three-day Eid, Muslims slaughter livestock and distribute the meat to the poor.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.