Profile in courage: He defied the advancing Taliban, and paid with his life

Loading...

| LONDON; AND KABUL, AFGHANISTAN

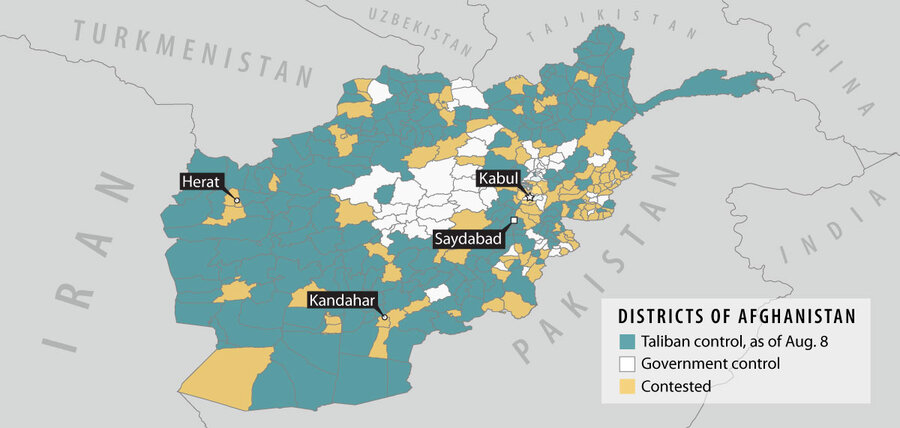

As of Sunday, the advancing Taliban insurgents had seized 229 of Afghanistan’s more than 400 districts, far more than the 66 controlled by the government. Last week in the capital, continuing an assassination campaign targeting officials, Taliban militants killed a former spokesperson of President Ashraf Ghani.

On Thursday, Amir Mohammad Malakzai, a highly respected and popular district governor, was gunned down in broad daylight in front of two of his sons. Family members say Mr. Malakzai had refused repeated Taliban offers of $500,000 in recent months to surrender his Saydabad district southwest of Kabul, and fended off daily death threats.

Why We Wrote This

As the Taliban sweep across Afghanistan, the assassination over the weekend of a district governor, interviewed by Monitor correspondent Scott Peterson in 2020, is a case study in loss, but also courage.

From one perspective, Mr. Malakzai’s killing is a case study in the extreme peril of standing on principle in defiance. Yet it’s also an example of how the Taliban’s ruthless tactics are spawning angry determination for revenge, signaling that a largely unwelcome jihadi takeover will not sit easily with a population bloodied into submission.

At his funeral, in an act of protest, Mr. Malakzai’s weeping daughter spelled out “Allah Akbar,” God is greater, with white stones. The Taliban complained that words they have used triumphantly for years are being turned against them. But in the past week, against the Taliban juggernaut, they have been turned into an Afghan rallying cry.

It was a small act of resistance against the Taliban, made by an Afghan daughter weeping at the grave of her beloved father, who was murdered by the insurgents.

The final resting place for Amir Mohammad Malakzai – a district governor gunned down in broad daylight Thursday, in front of two of his sons – could not have been simpler: a mound of dirt on a forlorn western Kabul hillside, marked on either end by two large black rocks.

Alone, draped in black and reading passages of the Quran, his 18-year-old daughter used white stones to spell out “Allah Akbar,” God is greater.

Why We Wrote This

As the Taliban sweep across Afghanistan, the assassination over the weekend of a district governor, interviewed by Monitor correspondent Scott Peterson in 2020, is a case study in loss, but also courage.

Those words have been used triumphantly by Islamist militants for years as they waged an ever-advancing insurgency against American troops and the Western-backed Kabul government. But in the past week they have been turned into a rallying cry by Afghans against a Taliban juggernaut sweeping across the country as foreign forces withdraw.

Taliban spokesmen complain that “infidels” are turning the chants of “Allah Akbar” against them, and warn that culprits will pay a price, even as the United Nations stated Friday that the Taliban offensive is exacting an “extremely distressing” human toll.

Mr. Malakzai – a highly respected and popular local leader, who family members say refused repeated Taliban offers of $500,000 in recent months to surrender his Saydabad district in Wardak province, southwest of Kabul – fended off daily death threats.

Those threats became so severe that the governor last month taught his wife and two daughters how to use weapons, with instructions to fight “to the last drop” of their blood, should the Taliban attack.

From one perspective, Mr. Malakzai’s killing is an example of how the Taliban’s ruthless tactics are spawning angry determination for revenge, signaling that a largely unwelcome jihadi takeover will not sit easily with a population bloodied into submission.

Yet as Taliban gains blot out more and more of the Afghan map, his death is also a case study in the extreme peril of standing on principle in defiance.

“My father taught me the lesson of courage, masculinity, and patriotism, and I want to follow his path so I could fulfill all my father’s aspirations,” says Mr. Malakzai’s eldest son, a graduate in engineering, who asked not to be named for his safety.

“He is a martyr of the homeland in the path of God, and I am proud of his martyrdom,” says the son, who would sometimes shadow his father to protect him if he left the house alone, without his five bodyguards.

Subterfuge, and an ambush

Mr. Malakzai’s second son and a younger one were with their father when they were on their way to a Kabul wedding. A man claiming to be a resident of Saydabad called, saying he was in urgent need of documents to be signed, and convinced them to drive to one address, then another.

Upon arrival at the last location, Mr. Malakzai stepped out of the vehicle. Three masked gunmen stepped out of an old vegetable shop and shot him in the head.

“Life is forbidden to me until I take revenge for my father,” cries the second son, a university student, his eyes bloodshot and barely able to speak.

“I am sure that God is with us, because in the last nights, in all the provinces of Afghanistan, all people chanted the slogan ‘Allah Akbar’ against the infidel Taliban,” says the eldest son. “In our country, every terrorist group has been destroyed with the words ‘Allah Akbar.’ Now is the time to destroy the Taliban.”

That aspiration may be easier said than done, no matter the level of personal outrage.

The Taliban have captured six provincial capitals in the past four days – including the northern prize of Kunduz – after not controlling a single one since 2016. Several other key provincial capitals, defended by increasingly exhausted Afghan security forces, are under Taliban assault.

By Sunday, the Taliban had seized 229 of Afghanistan’s more than 400 districts, far more than the 66 controlled by the government, with 112 still contested, according to the Long War Journal.

The vast majority have been overrun by the Taliban since President Joe Biden announced in April that the remaining several thousand U.S. troops would withdraw, unconditionally, by the end of summer.

No progress in peace talks

Thousands of NATO troops, who relied on the American presence for logistical support, have now left, too. A U.S.-Taliban deal signed in February 2020 included insurgent promises not to attack provincial capitals, and to start peace talks with the Kabul government. Those have made no progress.

Instead, U.S. airstrikes are being deployed to slow Taliban advances on cities. And Taliban commanders have told their fighters they have defeated a superpower and will soon achieve “victory” over the “infidel” Kabul government.

Mr. Malakzai told the Monitor in a February 2020 interview, “They tell their people ... ‘After the [U.S.-Taliban] deal is signed, we will create our own government, and kill and eradicate those who worked for the previous [U.S.-backed] governments.’”

Such an assassination campaign targeting officials, journalists, and civil society activists has already been underway for months. Last week in the capital, Taliban militants attacked the house of the defense minister, and Saturday killed a former spokesperson of President Ashraf Ghani.

The Taliban surge led to an emergency U.N. Security Council meeting Friday.

Afghans are “waiting apprehensively for a dark shadow to pass over the bright futures they once imagined,” the U.N. special envoy for Afghanistan, Deborah Lyons, told the council. “It is difficult for me to describe the mood of dread we are faced with every day.”

Afghanistan risks “descending into a situation of catastrophe so serious that it would have few, if any, parallels in this century,” warned Ms. Lyons. “This is now a different kind of war, reminiscent of Syria recently or Sarajevo in the not-so-distant past. To attack urban areas is to knowingly inflict enormous harm and cause massive civilian casualties.”

The dangers are felt most in personal stories of loss and doused hopes.

Afghans who worked with him since the Taliban era of the late 1990s, for example, say Mr. Malakzai, who earned a master’s degree in political science in Kabul after a journalism degree in Pakistan, was a selfless helper of his fellow citizens from Wardak. He worked with a charity, and then served for years on the provincial council, working on water and sanitation projects and expanding the school system to include girls’ education.

Taliban influence is wide in Wardak, and militants besieged Saydabad district in the spring. With the help of extra Afghan security forces and Afghan airstrikes, they were repelled after a month. One photograph from the time shows Mr. Malakzai, wearing camouflage and with an assault rifle slung over his shoulder, striding away from a military helicopter.

After the Taliban were repelled, Mr. Malakzai’s brother, Sawab Khan Wardak, says he received a request in late May to meet the Taliban. The insurgents told him they would give $500,000 if Mr. Malakzai would peacefully hand over his district – a common and effective Taliban tactic to buy off local officials and low-paid, embattled garrison soldiers.

Mr. Malakzai refused that offer, and several others made directly over the phone. But he was unable to marshal any more government troops. After another 10-day siege, the bullets ran out and the Taliban took over the district on June 27.

“He did not betray his country”

“My brother was not a traitor,” says Mr. Wardak. “Even though I was against his working in the government, I am proud that he did not betray his country and his people. He defended them with great courage.”

By contrast, Mr. Wardak blames weak government and corruption in Kabul for the inability to protect his brother – even in Kabul – and the inability to send reinforcements, leading to such swift Taliban advances.

“If there is strong will and the leaders of the government are not traitors, the Taliban are nothing – they can’t progress,” says Mr. Wardak. “But unfortunately we don’t have faith in our government.”

After Saydabad fell, the offers of Taliban cash turned to daily death threats against Mr. Malakzai. Worried for his life, he told friends he might not have long to live.

“Every time he came home, some guests came with him. He was always trying to help people,” recalls his tearful wife, who asked not to be named.

“I will never forgive the savage Taliban, and will teach my children to take revenge for their father by education, not violence.”