Wojciech Jaruzelski remembered as last Communist leader in Poland

Loading...

| Warsaw

Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski, the survivor of a Siberian labor camp, was an unlikely servant to the Soviet Union and its communist ideology.

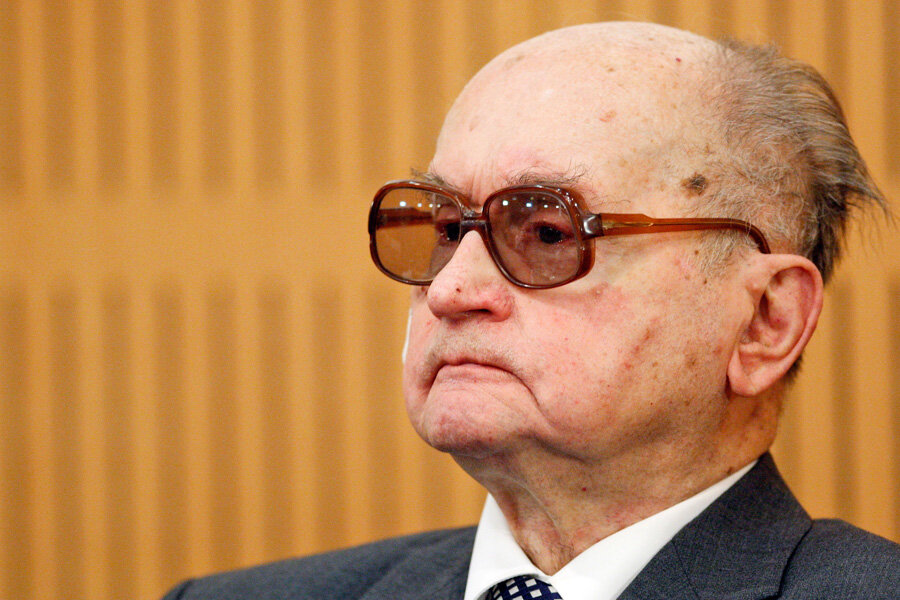

Poland's last communist leader, the general in tinted glasses who was best known for his 1981 martial law crackdown on the Solidarity union, died Sunday at age 90 after a long illness.

Born into a patriotic and Catholic Polish milieu, Jaruzelski and his family were deported to Siberia by the Red Army during World War II. That harsh land took his father's life and inflicted snow blindness on Jaruzelski, forcing him to wear dark glasses.

Despite his suffering at Soviet hands, Jaruzelski faithfully imposed Moscow's will on his subjugated nation until communism crumbled across the region in 1989.

Poland is still deeply divided over whether to view Jaruzelski as a traitor who did Moscow's dirty work or as a patriot who made an agonizing decision to spare the country the bloodshed of a Soviet invasion.

Jaruzelski stirs up these emotions for his defining act: His 1981 imposition of martial law, a harsh crackdown aimed at crushing the pro-democracy Solidarity movement founded months earlier by Lech Walesa.

Commenting on his death, Walesa called him a "great man of the generation of betrayal."

"Those times were complicated, I'm leaving the assessment to God," Walesa said.

Another of Jaruzelski's chief adversaries, communist-era dissident Adam Michnik, believes now that general had no choice.

"If you have to choose between martial law and a Russian military intervention, you should not hesitate," Michnik told The Associated Press on Sunday. "It's clear that it was the lesser evil."

Jaruzelski preferred to be remembered for the negotiations he backed eight years later that helped dismantle the regime and set Poland on track to become the thriving democracy it is today.

The suppression of Solidarity resulted in the imprisonment of thousands of dissidents, the deaths of dozens and economic stagnation.

"A tragic believer in Communism who made a pact with the devil in good faith" is how the Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulic described Jaruzelski.

The image of Jaruzelski in his drab olive military uniform announcing martial law on state television remains iconic to Poles. Straight-backed and betraying no emotion, he read from documents as he announced martial law and the outlawing of Solidarity, the first independent labor union in the communist bloc.

"The Polish-Soviet alliance is, and will remain, the foundation of Poland's state interest," he said.

For the next 18 months, Poles lived with curfews, dead phone lines and armed troops and tanks on the streets. Nearly 100 people died during the crackdown, while tens of thousands of Solidarity activists were imprisoned, including future Polish presidents Walesa â the Solidarity leader â and Lech Kaczynski.

Jaruzelski, who headed the government from 1981-85 and the party from 1981 until the communist regime's collapse in 1989, repeatedly defended his decision.

"The greater evil would have been a (Soviet) intervention," he said in a 2005 interview with the AP.

He sought historical vindication.

"The structures of the state were paralyzed. ... A general strike was imminent. We were staring hunger, cold, and blackout in the face," Jaruzelski said at Kansas State University in 1996.

"I spent the week prior to taking the decision on martial law as in some horrible nightmare. I entertained thoughts of suicide. So what held me back? The sense of responsibility for my family, friends and country," he said.

Jaruzelski claimed partial credit for negotiating the peaceful transition to democracy as Poland's last communist leader. Many Poles recognized him for allowing the "Round Table" talks with Solidarity in 1989 that paved the way for a peaceful transition to democracy. For about a year, he served as the president.

"Jaruzelski's role was positive, during the Round Table and after it," Michnik said. "He was a very loyal president toward the democratic changes that were taking place."

The Round Table talks came four years after Mikhail Gorbachev assumed leadership in the Soviet Union and launched his liberalization policies of glasnost and perestroika.

In his old age, Jaruzelski battled legal charges over imposing the clampdown and for crushing a 1970 workers' strike when he was defense minister that left dozens dead. As he underwent chemotherapy for cancer in 2011, a Warsaw court excused him from participating in the two trials.

Jaruzelski was born July 6, 1923, in the eastern Polish village of Kurow and attended an exclusive Catholic school.

When the Germans and Soviets carved up the country in 1939, he and his family were captured by the Red Army and deported to Siberia. During three years of forced labor cutting trees, Jaruzelski suffered snow blindness and injured his back.

He did not turn against the Soviet Union because he said he met kind and caring people there and was attracted to an ideology that seemed to address the social injustices he witnessed in prewar Poland.

In 1943, Jaruzelski entered a training school for Russian officers and fought the Nazis in a Soviet-backed Polish army. When Warsaw rose up against its Nazi occupiers in 1944, those Polish troops sat with the Soviet Army across Warsaw's Vistula River, watching, while the Nazis killed more than 250,000 people and leveled the city.

Recently released documents suggest that he participated from 1945-1947 in the suppression of Poles who resisted the imposition of Soviet-backed communism.

He joined the communist party and quickly rose through army ranks to become chief of the General Staff in 1965. As defense minister, Jaruzelski was one of the Warsaw Pact generals who planned the invasion of Czechoslovakia to crush its peaceful 1968 pro-democracy uprising. In 1970, he carried out orders to suppress workers' revolts in Gdansk and other coastal cities, a campaign that left 44 people dead and hundreds injured.

In 1971, he was appointed to the policy-making Politburo that was involved in the purge of Jews from the Polish military.

Jaruzelski became general secretary of the Communist party and prime minister in 1981, when Walesa's Solidarity was enjoying mass popularity, often expressed through strikes.

His commitment to communism - an atheist ideology - was so firm that when his mother died he didn't enter the church for her funeral service.

In 2006, the National Remembrance Institute state body that investigates communist-era crimes charged him with violating the constitution and leading an "organized criminal group of a military nature."

Jaruzelski attended hearings for both of his trials but was never convicted.

A left-wing-dominated parliamentary commission in 1996 spared him a trial before the State Tribunal over martial law. He battled heart problems, pneumonia and cancer that eventually led doctors to declare him unfit to stand trial.

He said he wanted his gravestone to say: Wojciech Jaruzelski - General.

Jaruzelski is survived by his wife, a daughter and a grandson. Funeral arrangements were not immediately known.