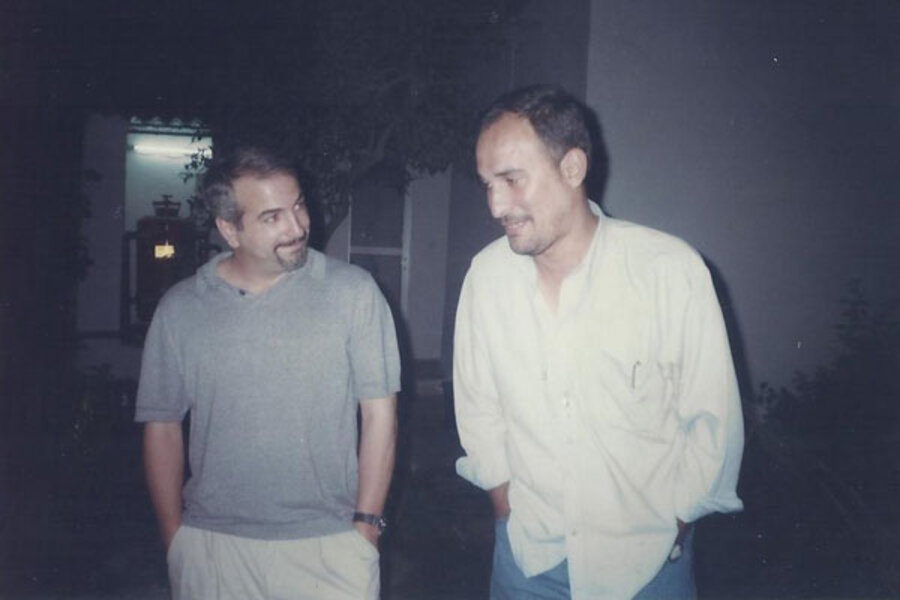

At work in Iraq with Anthony Shadid

Loading...

Reporters are cantankerous, competitive and frequently catty. Yet Anthony Shadid's sad and untimely death has brought forth nothing but praise and admiration from every corner. An old friend reminded me yesterday of a conversation in 2006 in which I told her that "Shadid, hands down, is the best reporter working in Iraq." I suspect all of us who covered the war there said that at one time or another. Like all of us, of course, he had help, particularly from Naseer Mehdawi, the Iraqi colleague who worked with him on the stories that landed Anthony the 2004 Pulitzer.

One of the reasons that Anthony inspired such love was his generosity of spirit and appreciation of others. He knew he wasn't out there alone. He wrote the following to Naseer in his copy of Anthony's 2006 book on Iraq, "Night Draws Near": "There is no better friend in this world, no colleague more loyal, no man who I admire more. This book should have your name on the cover! You are like my brother and always will be." Naseer has kindly shared his thoughts on Anthony and their collaboration below. - Dan Murphy

I remember the first time I met Anthony Shadid in February 2003. I had been working for The Washington Post in Baghdad with Rajiv Chandrasekaran and the photographer Michael Robinson Chavez. Anthony had joined Rajiv and me and Chavez. Rajiv introduced Anthony to me and told me that he was a great journalist. He had been working with another paper, but the Post hired him because he is the best. Then orders came from Phil Bennett, who was the Post’s assistant managing editor for foreign news at the time, that all the journalists of the Post should leave Iraq because the troops were gathering in the Gulf and the war would happen. But Anthony refused. He stayed and asked me if I would like to stay with him. I was very interested in journalism and looking at what might happen. Rajiv left with Chavez to wait in Kuwait. (They later returned after the war started.) It was only me and Anthony. Our driver was Karim Sadon. After that we were pretty much Anthony’s team, me and Karim. Everyone at the Post knew that we were Anthony’s guys.

I started my journey with Anthony looking for people expressing their feeling about what would happen. I had an instinct that the regime would collapse. I made up my mind to help him and support him. I took Anthony to Kadhamiya, a large Shiite neighborhood in Baghdad. All the people there hated Saddam because he was targeting them and killed many of their families during the uprising after the 1991 Gulf War. When I told Anthony about this, he was happy about the tip, and he started to get closer to me, to count on me. I had begun to think like Anthony, to know the kinds of stories he wanted, the people he wanted to meet. Anthony liked talking to people on the streets, the real people who were affected by Saddam and affected by the war. His confidence in me became stronger.

I remember that Saddam’s Information Ministry gave us an order to go to specific places. We refused. We went to forbidden places that no one dared to go except me and Anthony. At restaurants we’d talk about where to go next, all the places Saddam did not want us to see. We set out on daily trips with our brave driver, Karim, going to various parts of the country, meeting people, discussing issues, and making friends. We met workers at factories, farmers in the fields, government employees who were fed up with the restrictions of the regime, university students aspiring for an opportunity to be free and express their woes and dreams, clerics secluded inside their small mosques, and just simple, down-to-earth people. We listened to stories of women who had lost their husbands and sons in the many wars waged by the regime.

Out of this journey, I caught the journalism bug from Anthony. Before the war, I had been a foreign relations manager at the Ministry of Culture. When war broke out on March 20, 2003, I found myself feeling responsible for the safety of my family and my colleague, Anthony, who was in the midst of all the chaos. I did not want him to venture around without my advice and protection. I was worried, of course, about my own safety as well. I had a wife and children, who were toddlers when I met Anthony. During these events and after the war began, our relationship became stronger and stronger, and the trust between us became bigger and bigger. We treated each others like brothers. We were brothers. After the collapse of Saddam’s regime, the Washington Post started building a bureau in Baghdad, headed by Rajiv. I remember meeting the photographer Andrea Bruce and the others. Anthony and I continued on our journey, but this time out of Baghdad and out of the bureau. We went to Najaf together, to Fallujah, Ramadi, Basra, Kirkuk, Nasiriya, Tikrit, Haditha. We were spending so much time together, more time than I was spending with my family. We were the first people who met Moqtada Sadr in Najaf and wrote a story about him. We were the first people who found an informant in Duluiya. We were the first people who met insurgents fighting the Americans in Khaldiya.

Anthony was very aggressive in his work, and he was telling me that I was aggressive, too. We were a very good team. The stories were on the front page all the time. He was stylish in his writing. He was never afraid of going into danger. We had been through a lot terrible and dangerous places. When he was nominated for a Pulitzer for the best coverage in Iraq Anthony promised that he would share it, and he did. He shared the prize money with me after he won. He was very humble and kind. He appreciated the people who worked with him to help he tell his stories. He knew my secrets, I knew his. I introduced him to my family and my children, Yousi and Ahmed. He knew the dates of their birthday and sent greetings every year.

I left Iraq in 2004 because the insurgents sent me a threatening letter, condemning me for working with an Americans paper and for helping them. The letter said I deserved to be killed. Then they bombed my house on March 2, 2004. The Post, with Rajiv and Anthony, helped move my family to Amman, Jordan. Anthony escorted us there and helped us find a place. Anthony was on a break then to finish his book, "Night Draws Near." A few months later, we met again in Amman and decided to go back to work in Baghdad. I left my family in Amman in November 2004 and went back to Iraq to work with Anthony. I’ve since immigrated to Sweden with my family.

I am so devastated right now. I cannot believe that he is gone. I lost a dear and real brother first and a colleague second. He was a phenomenon in journalism, and I think no one can replace him. It is a very great loss to the journalism world. He was so brave, fearless, persistent, never gave up to find the truth and show it to the world. I am very proud and honored that I worked with him for more than four years, sharing with him the sadness and happiness that was Iraq. It is a great loss for me and my family, for journalism, and for his family and his two lovely children. God rest him in peace. He will be always remembered.