Healing step: Australia pledges $813M for Indigenous peoples

Loading...

| Canberra, Australia

Australia’s government on Thursday pledged 1.1 billion Australian dollars ($813 million) to address Indigenous disadvantage, including compensation to thousands of mixed-race children who were taken from their families over decades.

The AU$378.6 million ($279.7 million) to be used to compensate the so-called Stolen Generations by 2026 is the most expensive component of the package aimed at boosting Indigenous living standards in Australia.

The compensation of up to AU$75,000 ($55,400) in a lump sum plus up to $AU7,000 ($5,200) for expenses such as psychological counseling will only be available to mixed-race children who had been under direct federal government control in the Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory, and Jervis Bay Territory.

Most members of the Stolen Generations had been under state government control when they were separated from their Indigenous mothers under decades of assimilation policies that ended as recently as the 1970s.

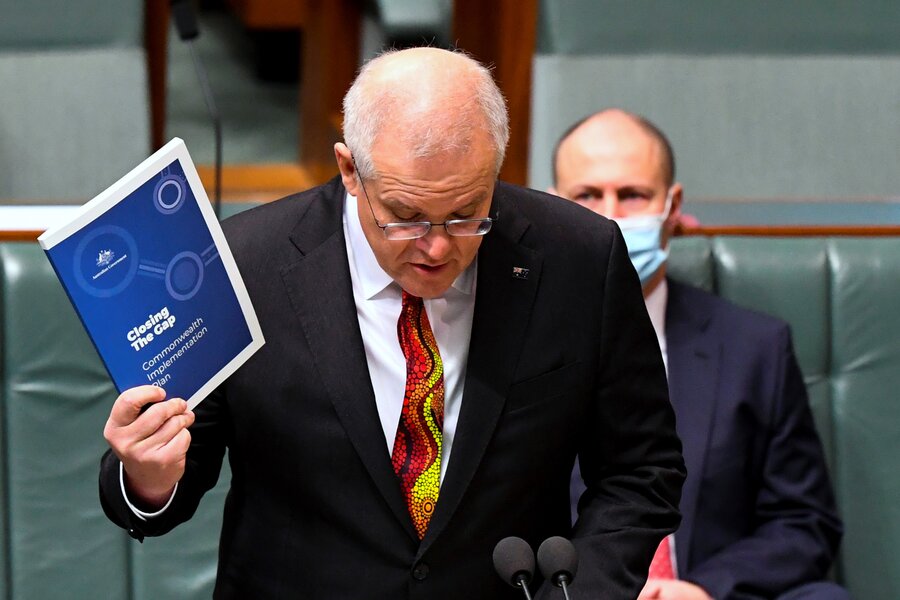

Prime Minister Scott Morrison said the compensation was a recognition of the harm caused by forced removal of children from families.

“This is a long-called-for step recognizing the bond between healing, dignity, and the health and well-being of members of the Stolen Generations, their families and their communities,” Mr. Morrison told Parliament.

“To say formally not just that we’re deeply sorry for what happened, but that we will take responsibility for it,” Mr. Morrison added.

Pat Turner, the Northern Territory-based Indigenous chief executive officer of the National Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organization, welcomed the compensation, which was recommended in 1997 by a government inquiry into the Stolen Generations.

“Many of our people have passed, including my mother, so it’s a sad day for those who have passed, but it’s a good day for those who have survived,” Ms. Turner said. Ms. Turner’s mother Emma Turner had been taken from her own mother in the 1920s and they didn’t reunite until the 1970s.

“It will never replace growing up with family, you can never replace that,” she added. “I hope this will give some relief to the survivors of the Stolen Generations.”

Australian states have legislated their own compensation plans for Stolen Generations survivors between 2008 and last year.

But Queensland and Western Australia, states with some of the country’s largest proportions of Indigenous people within their populations, do not have specific Indigenous compensation plans. Anyone who experienced neglect or abuse while in a Queensland or Western Australia state institution is entitled to compensation.

Ms. Turner said it was time Queensland and Western Australia also acknowledged the Stolen Generations’ human rights.

“I’m quite happy to say to the W.A. government and the Queensland government: Time’s up for redress of the Stolen Generations. You have to follow the other jurisdictions throughout Australia,” Ms. Turner said.

Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, the first Indigenous person appointed to the job, said his own mother Mona Abdullah was separated from her siblings in Western Australia from infancy until they were in their 20s.

“You can’t undo the emotional impact that that has,” Mr. Wyatt said.

Among the Stolen Generations members who won’t receive federal compensation is Lorna Cubillo.

In 2000, Ms. Cubillo lost a landmark Federal Court case against the Australian government seeking compensation for the abuse and neglect she suffered in a home for Indigenous children in the Northern Territory city of Darwin. She died in Darwin last year.

Indigenous Australians account for 3% of the population and have poorer health, lower education levels, and shorter life expectancies than other ethnic groups. Indigenous adults account for 2% of the Australian population and 27% of the prison population.

A center-left Labor Party government launched the ambitious Closing the Gap initiative in 2008 aimed at achieving equality for Indigenous Australians in health and life expectancy within a generation.

But Mr. Morrison’s conservative government last year scrapped the 12-year-old timetable, declaring the policy had failed.

Mr. Morrison said that among the most significant achievements of Australia’s pandemic response were the facts that COVID-19 had been kept out of Outback Indigenous communities and no Indigenous Australian had died from coronavirus.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.