As gay-marriage mail survey ramps up, so do Australian frustrations with politics

Loading...

| Melbourne, Australia

After more than a decade of political wrangling and failed legislative attempts, Australia is poised for a vote that could see it join the growing club of nations that allow same-sex marriage.

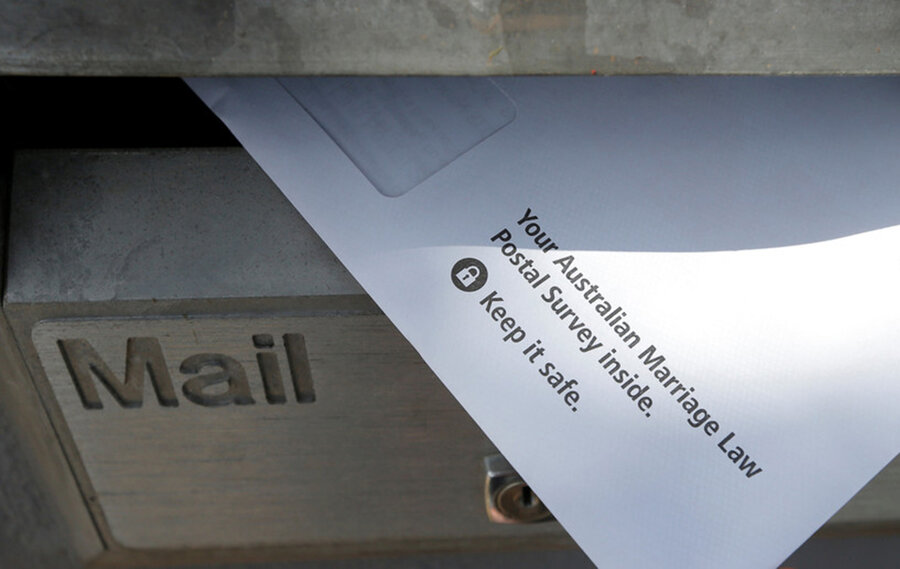

The decision isn’t taking place in parliament – at least not yet – or even at the ballot box. Whether Australia finally decides the hot-button social issue, which has defied a political resolution for years, may depend on a globally unique arrangement: a postal survey.

From Sept. 12 to Nov. 7, Australians can complete and return forms asking them one question: “Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?”

Straightforward as that seems, the story behind the survey is anything but. Rather, it’s an unusual political arrangement that, to many Down Under, feels out of touch with popular opinion. Polls going back to 2007 show steady majority support for gay marriage. And the process is unfair, gay advocates argue: Why should their rights be put up for public vote – and an odd one, at that? Unlike formal referenda, the mail survey is voluntary and nonbinding, more of a “suggestion” that parliament act, after repeated failures at legislation.

But the depth of political infighting and paralysis that has led to the postal survey also highlights many Australians' concerns about politics in the “Lucky Country” – a country often considered “Lucky” for gay residents, too. Amid economic anxieties – despite a world record-breaking quarter-century of growth – some view the so-called “plebisurvey” as one more example of a government that’s ineffective and out of touch.

“The sort of thing you’ve seen in Britain with the vote for Corbyn, you’ve seen in the United States with Trump, in France with Macron, and so on – it’s basically here,” says Ian McAllister, a politics professor at Australian National University in Canberra. There is “populist disaffection with the major established political parties and a distrust in their ability to deliver economic performance and sound policies.”

Political inertia

The center-right government led by Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has promised to hold a conscience vote on the issue in parliament if the public votes “yes,” after results are revealed Nov. 15. Seventy percent of Australians who say they are “certain” to return the survey back gay marriage, according to an Ipsos poll, meaning Australia could legislate for same-sex unions before Christmas.

If it does, it would join a club of two dozen countries where gay marriage is legal – a club many are surprised Australia didn’t join long before. Sydney’s annual Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras is one of the world’s largest pride festivals. In a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, 79 percent of respondents agreed with the question “Should society accept homosexuality?” That’s more than in the United States, Brazil, South Africa, or Argentina, all of which have now legalized gay marriage.

But successive parliaments have voted down change or blocked a vote from even taking place – reflecting deep divisions within the ruling party, and, critics say, the latest symptom of troubled leadership in an era of declining public trust.

Professor McAllister says the country hasn’t had a leader with consistently high public approval for a decade, fueling political inertia. “By and large, they are not willing to take positions on issues, and that’s certainly the case with Turnbull and same-sex marriage,” he says.

The voter survey arrangement reflects “a pathology within the parties,” says Graeme Orr, a law professor at University of Queensland.

They are “very sensitive to what you might call vocal minorities,” Dr. Orr says of politicians who’ve become reluctant to lead amid falling faith in government: a government that seems repeatedly hamstrung by issues that critics say should not be so controversial, given public support, or so preoccupying. Those range from the marriage “plebisurvey,” as it has been derisively called, to a commotion over politicians with dual citizenship, which one headline dubbed “the world’s most ridiculous constitutional crisis.”

Mr. Turnbull, an urbane ex-investment banker who supports same-sex marriage, is widely seen as wedded to the public vote out of fear of a back-bench revolt that could cost him the job he himself seized in his own party coup. Since 2007, the country has undergone five changes of prime minister.

When Turnbull successfully challenged predecessor Tony Abbot for leadership of the Liberal Party two years ago, he promised conservative colleagues that Australians would get to weigh in on same-sex marriage – a plan Mr. Abbot proposed to relieve tensions between intra-party factions by taking the question out of MPs’ hands.

After a formal plebiscite proposal was blocked by the Senate last month, the government settled on a postal survey instead, bypassing the need for parliamentary approval. Technically, it is not a ballot, but a collection of statistics about Australians’ view of the issue to guide parliament.

Discontent Down Under

For some voters, the complicated work-around is one more example of a deeply frustrating government. Trust in politicians last year plunged to a 40-year low, according to a study from Australian National University. Only one-quarter of respondents expressed confidence in the government, and four in 10 reported they were “not satisfied” with Australian democracy. A record 23 percent opted for a minor party at last year’s federal election, turning fringe groups such as the far-right One Nation Party into power players for the first time.

It’s a discontent that, for many, has roots in the economy. The Land Down Under has enjoyed an unprecedented string of growth, but some feel it has not been shared equally. Sixty-eight percent of Australians believe the economy is rigged in favor of the rich and powerful, according to an Ipsos poll carried out earlier this year, and more than 70 percent say they “need a strong leader to take the country back” from them. The share of income going to the richest 1 percent of the population has doubled since the 1980s, while wages are growing at the lowest levels in 20 years. Home ownership, a key plank of the “Australian dream,” has plunged to its lowest level since the 1950s.

“After 26 years of interrupted economic growth, Australians have a lot to be proud and pleased about,” says Nicholas Reece, a public policy fellow at the University of Melbourne. “That said, stagnant real wage growth and political instability at the national level has fed a growing pessimism in our politicians and the ability of the system to deliver difficult but necessary reform.”

Lamenting the state of economic policy, Sydney Morning Herald political editor Peter Hartcher recently complained that politics appeared to have devolved into a “parlor game of polls and perceptions.” It’s a common criticism of the “plebisurvey,” viewed as an odd political farce in a nation whose prosperity has bred a sense of navel-gazing complacency.

Indeed, Australia’s nickname “The Lucky Country” was first coined ironically, by the late social critic Donald Horne: a scornful comment on the lack of vision among the ruling elite, made possible by the country’s many geographical and historical advantages. “There is still some truth in that,” Mr. Reece says.

And though many Australians bemoan all the agitation around the marriage vote, it’s actually one more confirmation of Mr. Horne’s “lucky” theory, Orr suggests tongue-in-cheek: only a lucky country could afford to spend so much time debating “the process by which we might begin to consider having a parliamentary vote on same-sex marriage.”