Censored in Beijing: a correspondent watches himself fade to black

Loading...

| Beijing

It’s not as if I’ve been physically assaulted, I grant you. But I certainly feel violated – that nauseous sensation when you realize your home has been burgled.

I’ve been censored.

One moment I was on the TV screen, a guest of CNN’s “On China” talk show discussing press freedom in China, and the next I wasn’t. The screen went black. The Chinese censors had pulled the plug. Where there was light, they brought darkness. Nobody in mainland China could watch the program.

“Well of course,” you will say. “You are in China. What do you expect? The freedom to talk publicly about the lack of freedom?”

And, of course, I know perfectly well that almost all of my Chinese colleagues are censored, or forced to self-censor, every day.

But this was my first time. And the first time is different.

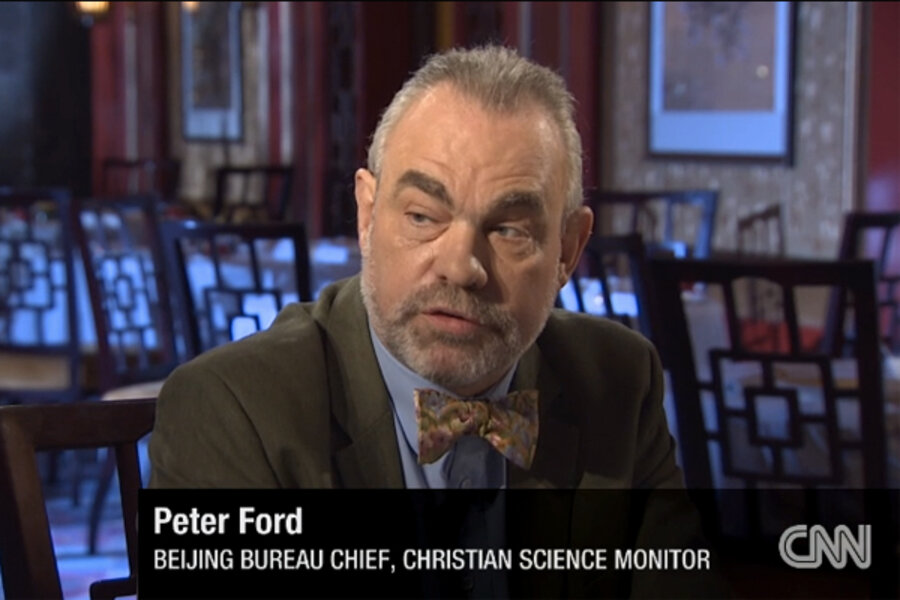

As well as my day job being The Christian Science Monitor’s correspondent in China, I am also president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China. That means people come to me when they want to know about foreign correspondents’ working conditions in China.

Those conditions have been getting worse in recent years. The Chinese government has even been denying journalist visas to reporters from newspapers it particularly dislikes, such as The New York Times.

So when CNN’s Kristie Lu Stout invited me onto her monthly talk show, along with another Beijing-based foreign correspondent and a Hong Kong journalism professor, I had plenty to say.

We taped the show in Hong Kong last month. But when it went out on Wednesday night, I had answered only one question by the time – four minutes into the conversation – the screen suddenly went black.

What did the Chinese censors think they were doing (aside from providing more grist to critics’ mills)? CNN is not generally available to Chinese homes; you have to have a satellite dish that only luxury hotels and special residential compounds for foreigners are allowed to install.

By killing the transmission, the authorities denied only a tiny, overwhelmingly foreign audience the chance to see the show. And it was hardly the stuff of which revolutions are made – three middle-aged intellectuals discussing the mechanics of censorship.

But even that, it seems, unnerves the Chinese government so badly that it did not dare let any of its citizens watch us. The censors had to stamp us out.

When I think about it, that is what made me feel sick: the authorities’ blunt declaration, with the flick of a switch, that I did not exist. It is an unsettling sensation.

But I do exist, and so do my colleagues. And here is a link to the discussion that the Chinese government does not want you to hear.

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/02/18/world/asia/on-china-journalism-transcript/index.html