Nuclear deal? New North Korea and Iran pact raises international concern

Loading...

| Seoul, South Korea

North Korea and Iran appear to be increasing their dealings in nuclear technology and missiles with each other under a breakthrough agreement reached between the two nations in Tehran three weeks ago.

“It’s likely the tempo of shipments of technology to Iran has increased,” says Bruce Bechtol, a former US intelligence official and author of two books and other studies on North Korea’s military buildup. “We have seen a large number of North Korean scientists visiting Iran.”

Concerns about the nature of North Korea’s exchanges with Iran have risen since Iran's science and technology minister, Farhad Daneshjoo, and North Korea’s foreign minister, Pak Ui-chun, signed the deal to cooperate on science and technology after a summit of “nonaligned nations” held in Tehran in late August.

North Korea and Iran have been cooperating for years but never previously had a framework agreement that confirmed their longstanding relationship and also made clear their desire to build on it. The timing of the deal is significant, since Israel has been pressing for concerted action against Iran’s nuclear program while North Korea, under new leader Kim Jong-un, has been coming out with harsh denunciations of South Korean policies.

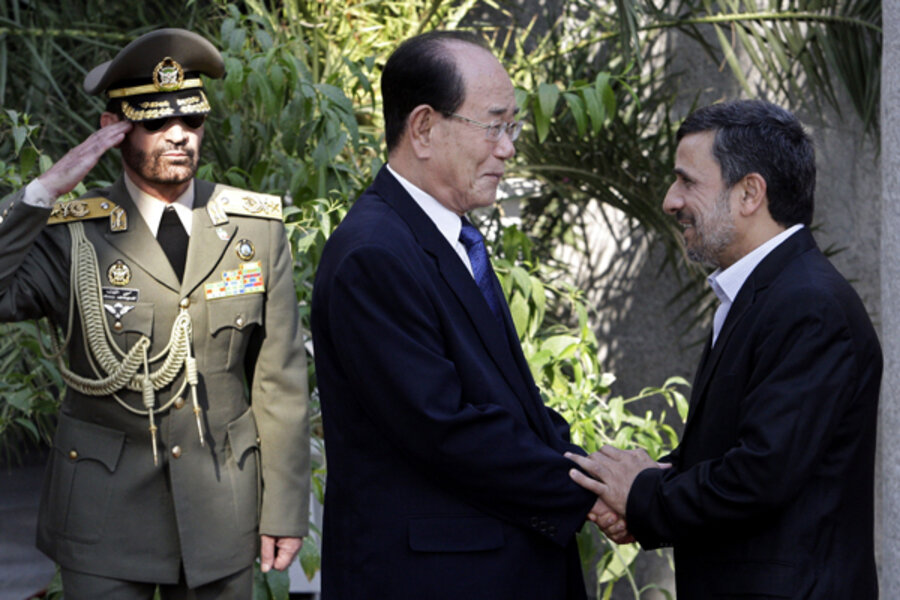

The bond between the two countries rests on the axiom “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” as Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, made plain. In a meeting with North Korea’s titular leader, Kim Yong-nam, president of the North’s Supreme People’s Assembly, visiting Tehran for the nonaligned conference, he observed that Iran and North Korea share "common enemies.” The United Nations, under strong US pressure, has imposed sanctions on both countries in an effort to stifle their nuclear ambitions.

The deal

Although details of the technology deal were not divulged, it broadly commits the two countries to “cooperate in research, student exchanges, and joint laboratories” in “information technology, engineering, biotechnology, renewable energy, the environment, sustainable development of agriculture, and food technology,” according to media reports from the government.

At the heart of this catchall listing, in the view of analysts here, lies a commitment for North Korea to step up shipments of missiles and other arms to Iran, along with technology. As of three years ago, North Korea was earning between $1.5 billion and $2 billion a year from these shipments, according to Larry Niksch, former researcher for the Congressional Research Service.

Both North Korea and Iran were members of the “A.Q. Khan network” – that is, the countries to which Abdul Qadeer Khan, the nuclear physicist responsible for Pakistan’s nuclear program, provided the technology for developing warheads from highly enriched uranium. North Korea now is believed to be nearing completion of a facility for developing highly enriched uranium, while Iran has advanced its enrichment to 20 percent – a few technical steps from weapons-grade, which is more than 90 percent.

There’s disagreement, however, on whether Iran, besides paying for North Korean missiles and nuclear technology in cash and oil, is also shipping centrifuges or centrifuge components. North Korean scientists were providing the technology and Iran the cash for building the nuclear reactor in Syria that Israeli planes bombed in September 2007. Iran has been plagued with delays in building more advanced centrifuges.

“I am afraid of an infusion of technology into North Korea,” says Kim Tae-woo, a longtime defense analyst and now president of the Korea Institute of National Unification. He believes North Korea is becoming the recipient of “the most advanced technology” under the terms of the document, which he sees as an escalation of a collaboration that has been going on for years.

Mr. Bechtol, whose latest book, “Defiant Failed State,” constitutes an indictment of the North Korean regime for its economic and military policies, demurs.

“North Korea is the seller, not the buyer,” he says, and in that role “continues to assist Iran in its highly enriched uranium program by providing scientists, centrifuge technology, and even raw materials.” North Korea, he notes, is rich in raw uranium and other natural resources.

As for how sales are faring at this critical time in Middle Eastern and northeast Asian history, says Bechtol, “North Korea is constantly changing its tactics, techniques, and procedures.”

Galvanizing a relationship

The growing relationship between Pyongyang and Tehran evokes memories of George W. Bush’s State of the Union message in 2002 when he famously said nations like Iran and North Korea “constitute an axis of evil aiming to threaten the peace of the world.” He also included Iraq, then led by Saddam Hussein, in the “axis.”

Later that same year, the confrontation with North Korea reached a critical stage with the breakdown of the 1994 Geneva framework agreement, under which North Korea had shut down its five-megawatt reactor and stopped producing plutonium for warheads. The Geneva agreement fell apart after the revelation in October 2002 that North Korea had an entirely separate, and secret, program for developing highly enriched uranium .

Use of the term “axis of evil” was widely criticized description of the growing relationship between Iran and Pyongyang as tensions rapidly rose between them and the United States. Mr. Bush himself did not use it again while encouraging six-party talks, hosted by Beijing, for North Korea to give up its nuclear program in return for a massive infusion of aid. Besides the US, China, North Korea, South Korea, Russia, and Japan also joined in the talks, culminating in 2007 in agreements for North Korea to halt its nuclear program.

“I’ve never been a fan of the axis-of-evil concept,” says Stephen Bosworth, former US envoy on the North Korea issue, visiting Seoul, South Korea, this week. He adds, however, that Tehran and Pyongyang constitute “a dangerous problem” since North Korea never honored the 2007 agreements and also violated an agreement reached between US and North Korean envoys in Beijing on Feb. 29 by test-firing a long-range missile April 13.

“It’s never reassuring to see two countries like Iran and North Korea talking to each other,” says Mr. Bosworth. “Clearly at this point formal diplomacy with North Korea has come to an abrupt halt.”

The failure of the February leap-year agreement "adds to the general skepticism about engagement with North Korea,” says Bosworth. He predicts “a process of watchful waiting over the next few months” to see if North Korea will want to return to talks with South Korea, which elects a new president in December, and with the US, which is expected to look for openings for talks regardless of who wins the US presidential election.

Analysts warn, however, that an escalation of dealings between Iran and North Korea may backfire. The agreement “doesn’t serve the interests of either power,” says Lee Jong-min, dean of the graduate school of international studies at Yonsei University, in South Korea. “This is one reason for tougher sanctions on Iran. On the North Korea side, this would rule out any cooperation with the US.”

Getting around sanctions?

One question is how North Korea and Iran get around sanctions and also get past US and other vessels blocking passage by sea under terms of the multination proliferation security initiative.

“Yes, some of these sales are going through merchant shipping that transits Chinese ports,” says Bechtol. “Other shipments are likely going on transport aircraft that transit through other countries.”

And, he adds, “Of course, the North Koreans also likely use merchant ships to proliferate a variety of technology and military equipment to Iran that follow routes through the Indian Ocean and elsewhere.”