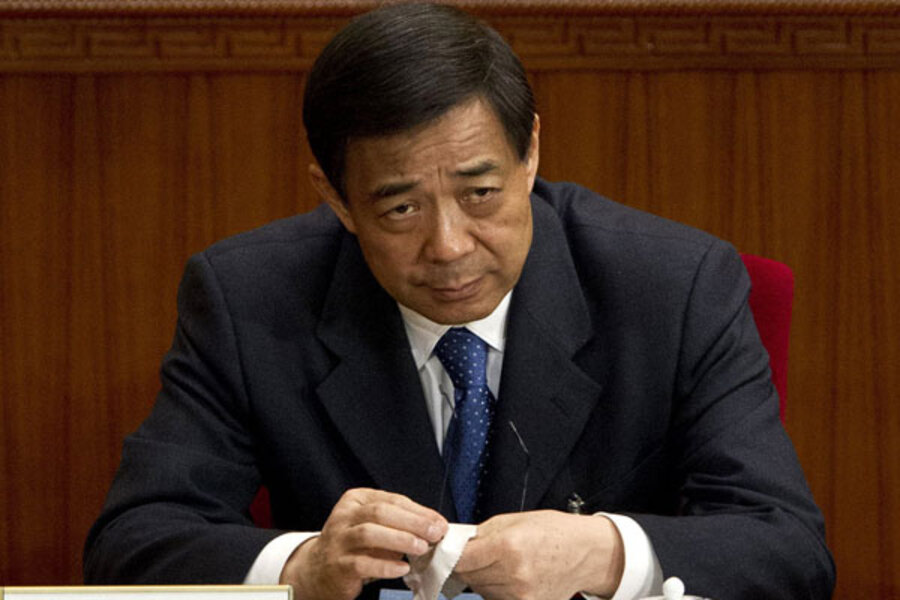

China's Bo Xilai affair: where the case stands

Loading...

| Beijing

When British businessman Neil Heywood was found dead in his hotel room in the southwestern city of Chongqing in November, the discovery attracted little attention.

Neither the fact that the police said he had died of alcohol poisoning (when he was known to drink only rarely) nor the fact that his body was hastily cremated without an autopsy (unusual in China) – nor the unexplained presence of police at the cremation, appeared to arouse undue suspicion.

Today, suspicion swirls around every aspect of his death, not least because the Chinese authorities now say that the wife of one of China's best-known and most powerful politicians, Bo Xilai, is "highly suspected" of having ordered Mr. Heywood's murder.

Both Mr. Bo and his lawyer wife, Gu Kailai, are currently in detention and under investigation, and have not been seen publicly for more than a month.

Heywood's death and the Bo couple's detention are two of the few indisputable facts in a murky affair whose political ramifications are magnified by Bo's importance: Until scandal overtook him, he was a contender for one of the top nine jobs in the ruling Communist Party. It is clear to anyone familiar with the way Chinese politics works that Bo's enemies have used and amplified the scandal to bring him down.

Almost everything else about the case is speculation based on unidentified sources whose motives in recounting the case's details are unclear. The police have said nothing, and the absence of reliable information has left the field clear for a welter of dramatic rumors, spreading like wildfire on the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, ranging from the type of poison used to kill Heywood to an impending military coup.

The case began to crack open Feb. 7, when photographs appeared on Weibo (China's version of Twitter) showing an unusual congregation of police outside the US Consulate in Chengdu, 170 miles from Chongqing. Two days later, another blogger posted the passenger manifest of a flight from Chengdu to Beijing showing that Bo's right-hand man, Wang Lijun, had taken that flight in the company of a vice minister of security.

Mr. Wang, it transpired, had fled to the US consulate, apparently seeking asylum, but left of his own accord when he was sure that regional police loyal to Bo wouldn't take him into custody.

Wang was almost certainly not going to be given asylum by the United States. He had been the chief of police in Chongqing during Bo's noisy antimafia campaign, which critics and victims complained had relied heavily on torture. But before handing himself over to the Chinese security chief and disappearing into an interrogation room somewhere, Wang showed US diplomats a police file suggesting that Ms. Gu had been involved in Heywood's murder.

Why would Wang have betrayed his mentor? A few days earlier they had had a falling out; Bo had fired Wang as police chief and demoted him to an innocuous municipal job. According to people familiar with the reopened police investigation into Heywood's death, Bo did so after Wang had shown him the evidence of his wife's involvement.

Why Wang even brought up the matter with his boss, when it had until then caused no waves, is unclear. But Bo's reaction seems to have made Wang fear for his life and seek protection.

It was not long before the official Xinhua news agency announced that Bo had been removed from his post as head of the Chongqing Communist Party committee.But a month passed before he was fired from its elite 25-member Politburo, suggesting fierce debate over his fate.

In the meantime, stories had begun to appear on Weibo and in foreign media detailing allegations that Gu had made hundreds of millions of dollars selling government jobs in Chongqing, that Bo had seized the assets of businessmen felled by his antimafia campaign and used them to swell municipal coffers, and that Heywood had been a close friend and business partner of Gu's, helping her to invest her millions abroad illegally.

Heywood, a 40-something Englishman with a penchant for cream linen suits, Jaguar cars, and sailing boats, first got to know Bo when Bo was running the city of Dalian, on China's east coast, more than a decade ago. Heywood apparently helped Bo's son Guagua get into Heywood's alma mater, Harrow, the exclusive (and expensive) English private school, and traded on his privileged connections in his role as a business consultant.

The Xinhua report that Gu was a suspect in Heywood's death said only that the two had had "a financial dispute" without giving details of a motive she might have had for killing him. That did not stem a flood of allegations on Weibo that the two had been lovers and that Gu (or Bo) had killed him in a crime passionnel.

Neither Gu nor Bo has yet been charged with involvement in the alleged murder. Bo has been publicly accused only of "grave disciplinary violations" – a party issue, not a legal one. But it is almost inconceivable that Xinhua would declare that Gu had been detained as a murder suspect unless she was going to be formally arrested, charged, tried, found guilty, and sentenced, probably to death. If Bo did seek to block an investigation of his wife, he would be an accessory after the fact, a crime punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

Public pressure in China for a full accounting of the facts behind Heywood's murder and Bo's fall is not all that the government here has to deal with.

The British authorities have also been demanding a proper investigation of the death since February. Only on April 10, after four British requests, did Beijing inform London of a police investigation.