A century after the Revolution, Mexico could make it harder to expel foreigners

Loading...

| Mexico City

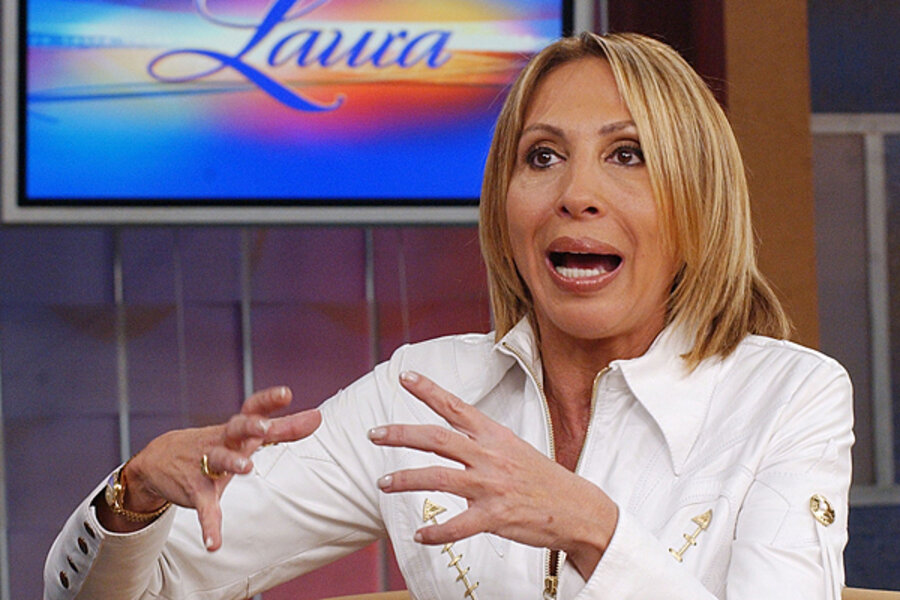

After twin storms hit Mexico simultaneously last month, TV talk show host Laura Bozzo hitched a ride with rescue crews, helicoptering into an impoverished village in Guerrero state – ostensibly to lend a helping hand. But when allegations surfaced that Ms. Bozzo staged a made-for-TV spectacle – preventing the state government helicopter she arrived in from distributing supplies to incommunicado settlements – some outraged citizens on social media called for a uniquely Mexican punishment for the Peruvian-born reporter: expulsion.

Article 33 of the Mexican Constitution permits the president to discretionally expel anyone deemed non grata. It also prohibits the participation of foreigners in Mexican matters – mainly politics.

But President Enrique Peña Nieto has proposed reining in some of the excesses of Article 33. He sent a constitutional amendment on Tuesday to the Senate, which would allow anyone ordered out of the country the right to a hearing in which they can present evidence, consult legal council, and receive consular assistance. They can also seek injunctions known as “amparos” against unfavorable outcomes – previously unattainable since the Supreme Court would traditionally defer to the president.

With the proposed changes, “You begin to institutionalize the procedure,” says Federico Estévez, political science professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico.

The proposal, Mr. Peña Nieto said in the amendment documents, would allow Mexico to adhere to its international obligations in human rights matters, along with providing “minimum conditions to assure the adequate protection of [foreigners’] rights, that’s to say, due process.”

A change to Article 33 moves Mexico yet further away from anti-foreigner sentiments so prevalent after the Revolution of 1910, when the winners – who took up arms, demanding, “Land and liberty" – wanted to avoid a rerun of the Porfiriato, the period of President Porfirio Díaz, who often favored foreigners and their investments at the expense of ordinary Mexicans.

It’s also another step in the opening of a country so closed 25 years ago (prior to the signing of NAFTA) that kids would buy contraband candy like Snickers bars – smuggled from the United States – in itinerant markets.

With Mexico having signed free trade agreements with more than 40 countries and the current administration attempting to open the North American country to even more commerce, analysts say the scrapping of the excesses of Article 33 sends the right signal.

“It’s a good strategy by the administration,” says Arturo Pueblita Fernández, constitutional law professor at the Iberoamerican University. “It lets [investors] know, ‘Mexico is open for doing business.’"

Freezing out foreigners

The Mexican constitution still places some prohibitions on foreigners: only citizens can serve in the military or captain Mexican-flagged ships.

But changes have been made, too: foreign priests, for example, were previously not allowed to work in Mexico. Also, an amendment approved in the lower house of Congress last spring would allow foreigners to buy properties in coastal areas. The Senate still must approve the measure.

Still, Article 33 has long stood out among Mexican laws, somewhat spooking foreigners – mainly due its discretionary application, says Mr. Fernández, whose great-grandfather, an Italian immigrant and printer by trade, was expelled from Mexico for printing pamphlets in the 1930s for an opposition movement.

More recently, the government expelled Europeans in Chiapas state for alleged improper meddling in the 1990s Zapatista uprising.

The Interior Ministry, which is responsible for the National Immigration Institute, has also used Article 33 to kick out foreigners and “avoid the extradition process,” says Luis Guillermo Cruz Rico, a Mexican lawyer now working in Toronto.

Mr. Cruz and other observers say proposed amendments to Article 33 show how far the fear of foreigners has fallen in Mexico, and how it no longer moves the masses.

“It’s a convenient rhetorical device,” for some politicians, Mr. Estévez says.

“But it doesn’t get you much mileage anymore.”