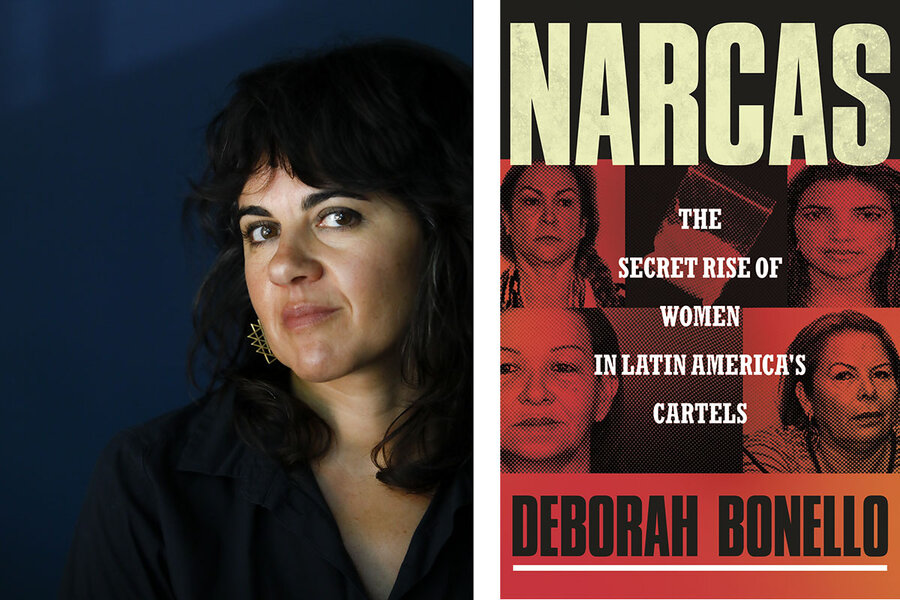

‘Narcas’ sheds light on the women who run drug smuggling cartels

Loading...

| Mexico City

From Al Capone to Pablo Escobar, organized crime and the men in charge of running it have long been subjects of public fascination. But what is lost when our view of such a far-reaching phenomenon as drug trafficking is narrowly focused to include only men?

A new book by Mexico-based journalist Deborah Bonello looks at the women behind the scenes – and at the top – of the Latin American drug trade. She finds them in all kinds of unexpected and influential places.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOrganized crime is not just a man’s job. Women work behind the scenes, and at the top, of the Latin American drug trade in unexpected and influential places, a new book finds.

Her research has been “a massive eye-opener,” she says, but law enforcement has not paid much attention to women in the drug business, allowing them to operate under the radar. This, says Ms. Bonello, “reflects the assumptions and the gender tropes that are going through the minds of people working on these cases.”

The author does not admire the subjects of her book but says she respects them for making their way in a male-dominated business in highly macho Latin American societies.

“If women are in the kitchen and these things are being discussed,” Ms. Bonello says she was once told, “they’re not just standing there stirring the sauce.”

From Al Capone to Pablo Escobar, organized crime and the men in charge of running it have long been subjects of public fascination. But what is lost when our view of such a far-reaching phenomenon as drug trafficking is narrowly focused to include only men? “Narcas: The Secret Rise of Women in Latin America’s Cartels,” a new book by Mexico-based journalist Deborah Bonello, digs into that question. She looks at the role of women behind the scenes – and at the top – in the Latin American drug trade, and why their stories matter. She recently spoke with the Monitor’s Whitney Eulich.

Why did you decide to write this book?

As a reporter who has covered organized crime since I got [to Mexico] in 2006, I always felt outnumbered by the men around me documenting organized crime. And they just didn’t seem to see the women [in the story]. Or, if they did, they were dismissed or minimized by their sexual or familial relationships to men.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOrganized crime is not just a man’s job. Women work behind the scenes, and at the top, of the Latin American drug trade in unexpected and influential places, a new book finds.

Elaine Carey [a scholar on women in the drug trade] put it best when she said to me once, “If women are in the kitchen and these things are being discussed, they’re not just standing there stirring the sauce.” Women are involved in the way decisions are made; they have a huge amount of control over the men and women around them.

I wanted to see what I would find if I focused on the women. So, it sort of started off as an experiment, trying to apply a much more nuanced understanding of power. But then the more I looked, the more I found these very high-profile, high-ranking women. And then it just became a major obsession.

What were some of the challenges?

The book was definitely a tightrope-wire walk. I wanted to profile these women ... who are very high profile in traditionally male roles, and show that they are more than just girlfriends and wives. But I also had to be very careful, because they aren’t [U.S. soccer star] Megan Rapinoe or [tech executive] Sheryl Sandberg, so you can’t celebrate them in the same way. They are working for viscerally violent organizations that are a major threat to public security and public health.

Does including women in this narrative change how we should be approaching policies on the drug trade?

I do hope that the book will be read by prosecutors and lawyers and people who work in the DEA [Drug Enforcement Administration] and FBI and just shake up their thinking a little in the way they approach the drug trade, both in terms of penalties and incarceration but also in terms of the root causes driving people into it.

The way current drug-related policies are implemented in Latin America is flawed. The majority of women who are in prisons are there for low-level trafficking offenses. We’ve seen the female prison population in Latin America surge enormously over the last couple of decades. Prosecutors and defense lawyers told me that women take advantage of the fact that they are women and might go under the radar, which I can only think reflects the assumptions and the gender tropes that are going through the minds of people working on these cases. It’s flawed.

Meanwhile, Bonnie Klapper, who is a prominent criminal lawyer, said to me once, if there’s a female Chapo [Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, former head of Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel currently in a maximum security prison in the United States] out there, then no one is looking for her. The common assumption is that there wouldn’t be one. And you find what you’re looking for, you know? And for a long time, we just haven’t been paying attention to women.

Violence isn’t the only lens for power. If you look at organized crime from a logistics standpoint, if you go after the money, you go after the transportation networks, increasingly women are operating in these areas. Chapo’s chief money launderer was a woman. When you look at it more holistically, the role of women is strong. It’s just much more nuanced than who is pulling the trigger or sending someone to pull the trigger. I think we’ve been blinded by our gender expectations of women.

What surprised you?

A really interesting part of the story for me was the different types of power that women see available to them. Across Latin America, it’s difficult for women ... with high levels of femicide and just general contempt for women who overstep any kind of traditional boundaries set out for them. I think power motivates us all in some way. I get it. I just don’t think women in this region have as many options.

Some of the women I met had law degrees. They had business experience. They’d started their own businesses. And clearly at some point, the drug trade just seemed like the best option. An ex-DEA guy told me that Central America’s most prolific drug trafficker – had she gone to work for a legit company, she’d be on the Forbes 500 list right now. It’s a lot of the same skills, dealing with logistics and relationships.

I’m curious to see what the feminist response will be to this book. I think one of the things that I really wanted to emphasize is that women do have agency and are making decisions every step of the way. This idea that women in the drug trade are just mules who are obliged to do it or women who tolerate what their husbands do – I just feel like that’s not a realistic perception of how things shake out. There’s a point where there’s always a limit on how many choices you have, but you are making them.

Is this book meant to be empowering or generate admiration?

I’ve never doubted [women’s] capacity to run a business or win a football game. So, why would I ever have underestimated us in this sense? It’s been a massive eye-opener.

I can’t say I admire these women, but I respect them. I think to make it, to make your way up in a powerful, male-dominated organization, is no small thing. I am in awe of their ability to work their way up while managing to stay so far off the radar of the anti-narcotics people. I do respect their achievements in the context of that world, but I can’t condone the actions of their organizations.