Is China’s birthrate slump a sign of global things to come?

Loading...

| Madrid and Boston

When the Chinese government imposed its one-child policy in 1980, the authorities feared an impending overpopulation disaster. Four decades later, they are worried by the opposite – the possibility of a population collapse.

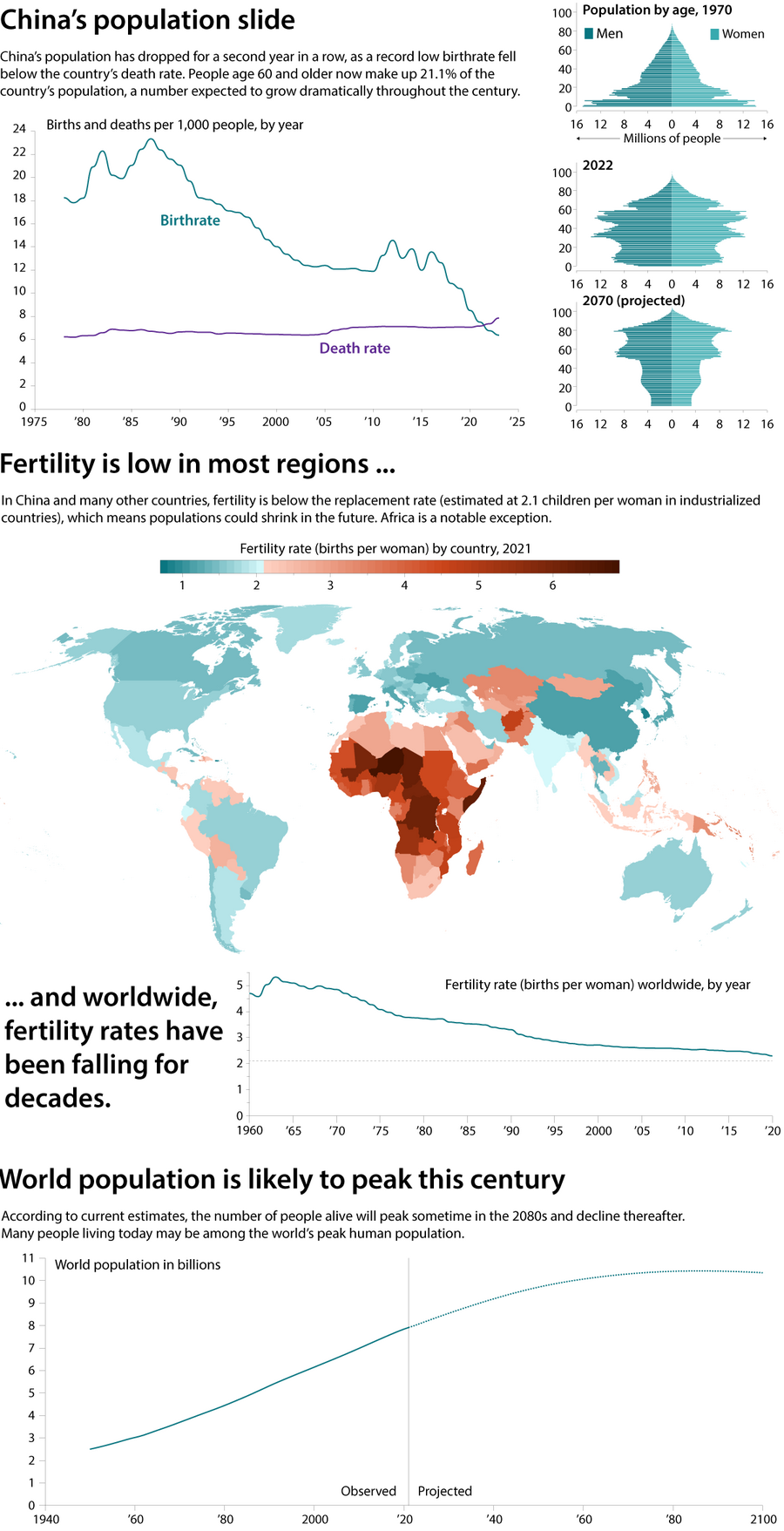

Last week, China announced a drop in its population for the second year in a row. Its birthrate is nearing one child per woman, less than half the population replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman.

Why We Wrote This

Widespread fears of global overpopulation have now turned into concern about a population slump. Is China’s plunging birthrate a sign of things to come elsewhere?

The declining population dilemma is attracting attention around the world. Birthrates are falling on every continent, raising questions about how humanity can and should respond. Demographers expect the world’s population to peak sometime in the second half of this century; whether it will then stabilize or plummet is uncertain.

But most experts warn against drawing long-term conclusions, especially those that spell disaster. To be sure, lower birthrates will have economic consequences – slower economic growth, perhaps, and fewer young people paying into their elders’ pension funds.

But “to have lower fertility is not necessarily a negative situation,” says Patrick Gerland, a senior official at the United Nations Population Division. “It’s more, how does society adapt to this new reality?”

When the Chinese government imposed its one-child policy in 1980, the authorities feared an impending overpopulation disaster. Four decades later, they are worried by the opposite – the possibility of a population collapse.

Last week, China announced a drop in its population for the second year in a row. The government is scrambling to reverse what demographers classify as an “ultralow” birthrate nearing one child per woman, less than half the population replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman.

The declining population dilemma is attracting attention around the world. Birthrates are falling on every continent, raising questions about how humanity can and should respond.

Why We Wrote This

Widespread fears of global overpopulation have now turned into concern about a population slump. Is China’s plunging birthrate a sign of things to come elsewhere?

“In the long run, if humanity’s average birthrate goes and stays below two, then the size of the human population will decrease,” says Dean Spears, associate professor of economics at the University of Texas at Austin. “There is no reason to be confident [the trend] is likely to reverse course soon or automatically.”

Almost everywhere, parents are choosing to have fewer children, whether for economic or personal reasons. Two-thirds of the planet’s population now lives in a region where the fertility rate has fallen below the replacement level, from 1.7 in the U.S. to 1.5 in Europe and 1.2 in East Asia.

Birthrates are higher in sub-Saharan Africa, but they are dropping there, too, from 6.8 to 4.6 births per woman since 1980. The global average has fallen from five births per woman in 1950 to 2.3 in 2021, often driven down by greater economic prosperity and women’s empowerment.

Demographers expect the world’s population to peak sometime in the second half of this century. Whether it will then stabilize or plummet is uncertain; if the whole world’s fertility rate followed the U.S. example, global population could decline as quickly as it has risen over the past two centuries.

But most experts warn against drawing long-term conclusions, especially those that spell disaster.

“To have lower fertility is not necessarily a negative situation,” says Patrick Gerland, a senior official at the United Nations Population Division. “It’s more, how does society adapt to this new reality?”

For generations, most people have worried about the threat of overpopulation. Books such as “The Population Bomb,” published in 1968, warned of mass global famine and upheavals caused by a coming population explosion. It was later deemed alarmist and largely inaccurate, which is not to say that countries with the highest birthrates do not still have difficulty meeting their citizens’ basic needs.

Lower birthrates lead to different economic dilemmas. Increasing life spans are a sign of global progress. But if fewer children are born and grow up to find jobs, that means there will be fewer working-age individuals to support retirees through traditional pension and healthcare systems. And a smaller pool of innovators and entrepreneurs, as well as consumers, could mean lower economic growth in the future.

Making it easy for couples to raise children may be the best way to encourage them to do so, says Dr. Gerland. He points to France and the Nordic countries as places whose family-friendly policies – from affordable child care to generous parental leave – may have helped stabilize, or even slightly increase, fertility rates in recent years.

Raising fertility rates, he says, “usually means a lot of social support to families, and especially combining work and family. To do it alone is very difficult.”