Drone drops drugs into Ohio prison yard: The newest smuggling method?

Loading...

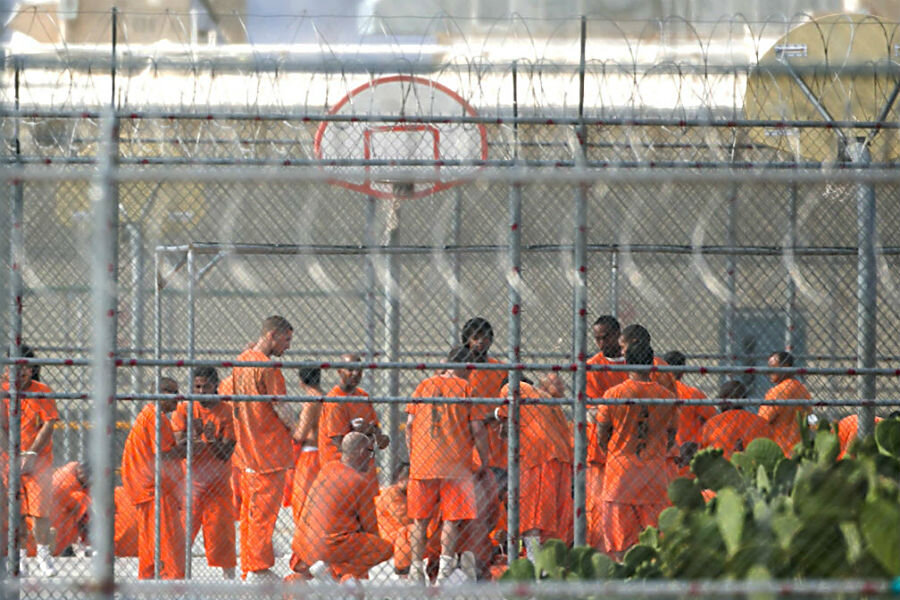

Officials at Mansfield Correctional Institution in Ohio say a fight between inmates last Wednesday was caused by a drone dropping more than 7 ounces worth of heroin, marijuana, and tobacco into the prison yard.

The use of drones to smuggle drugs, cell phones, and weapons into correctional facilities has become relatively common in recent years as drones become cheaper and more accessible to the public, experts say.

The machine most commonly used for delivering prison contraband can be bought on Amazon for as cheaply as $400, CBS News reports. Some analysts predict that upwards of one million drones will be sold in 2015.

As this method of smuggling grows increasingly popular, lawmakers and prison officials struggle with how to regulate the small flying robots.

Washington State Senator Pam Roach (R) introduced a bill in February that would tack an extra year onto the prison sentences of criminals who use drones for illegal activities. (Attempting to cross prison guard lines with contraband is a felony that carries a maximum sentence of 20 years in the US.)

In South Carolina, authorities built new towers on state correctional facility grounds that enable officers to keep an eye on the surrounding skies.

Bryan P. Stirling, the director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections, said he never expected drones to be an issue when he became the head of the state’s prison system in 2013.

“When I started in this job it was all very futuristic – Amazon wasn’t even talking that much at that point of using them to make deliveries,” he told the New York Times. “Now it’s something we’re having to devote extensive resources to.”

Some prisons have taken advantage of the website No Fly Zone, where individuals, business owners, and others who don’t want drones flown overhead can enter their addresses into a database. Those addresses are then provided to drone manufacturers who have agreed to program their devices to not fly over those locations.

Other institutions have enlisted the help of a drone detection device called Drone Shield to intercept the packages before they reach their destination.

While one drone may seem like a relatively harmless form of smuggling when used to sneak in a cell phone or a few ounces of drugs, the technology could be extremely dangerous if 10 or even 100 drones were programmed to deliver contraband simultaneously, says Brian Hearing, the co-inventor of Drone Shield.

"You talk to prison officials, and it's easy to dismiss one or two weapons, but it's less easy to dismiss dozens of weapons," Mr. Hearing told CBS News. "It can quickly turn from a hostage situation into a full-blown riot with multiple weapons.”

The trend of contraband delivery via drone began a couple of years ago and has spread around the world, with incidents documented in countries including Brazil, Ireland, Greece, Russia, Switzerland and Australia.

David McCauley, acting industrial officer for the prison officer’s vocational branch of the Public Service Association in Melbourne, Australia, told The Guardian that this method of delivery is a logical evolution for smugglers.

“At the end of the day if they can throw tennis balls over the wall with drugs in them…it’s going to be very difficult to stop these drones,” Mr. McCauley said.