On gun violence, blaming mental illness may only deepen stigma

Loading...

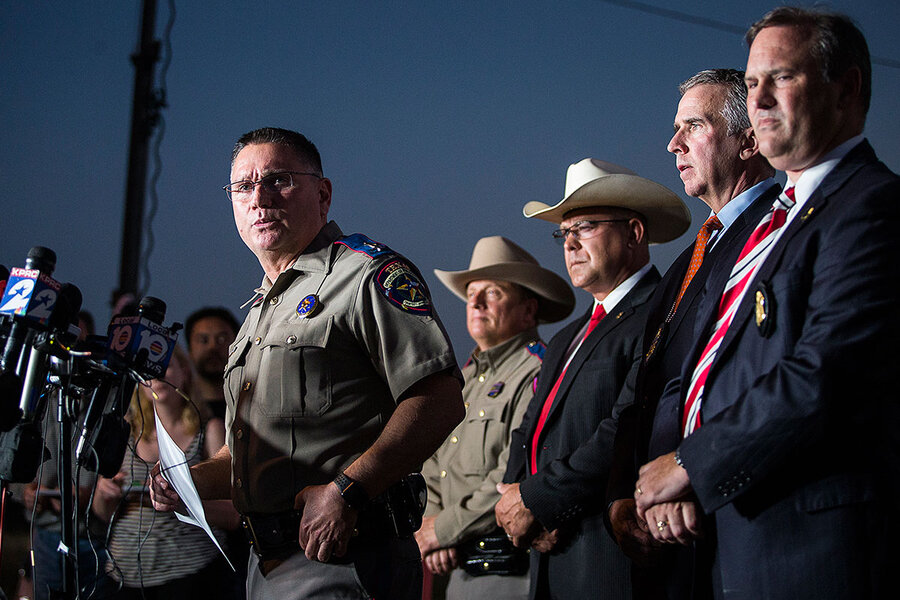

| Sutherland Springs, Texas; and Los Angeles

The day after Devin Kelley perpetrated America’s worst mass shooting in a place of worship – killing 26 and wounding another 20 at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas – President Trump called it a “mental health problem at the highest level.”

Some mass shooters have been diagnosed with mental illness. Jared Loughner, who killed six and severely wounded then US Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in 2011, was found by psychiatrists to have a mental disorder. Ditto for James Holmes, who killed 12 people at the Century movie theater in Aurora, Colo., in 2012.

Mr. Kelley himself escaped from a mental health facility in New Mexico in 2012, after being accused of assaulting his wife and severely beating his baby stepson while serving with the US Air Force.

But few mass killers have a clinically diagnosed mental illness. Thus, pointing to mental illness as the cause of gun violence is not only misleading, say mental health and gun violence experts, it could also increase the stigma around it and make people less willing to seek help.

“Imagine if [Mr. Trump] had said, ‘veteran’ – that this was a ‘veterans’ issue,” says Jeffrey Swanson, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C. “He’d besmirch the whole community. Well, that’s what he’s doing with mental illness.”

The best indicator of future violent behavior is past violent behavior, experts say. A history of animal cruelty, childhood maltreatment, access to guns, and being young and male are also more reliable indicators of future violence than a diagnosed mental health disorder, they say.

Perpetuating stereotype

Only 3 percent to 5 percent of violent acts can be attributed to a person living with a severe mental illness, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, while people linked to those illnesses are actually 10 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population. Of 88 mass shooters – those who had killed four or more people in the US – since 1966, only 14.8 percent were diagnosed as psychotic, according to 2015 paper by Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox, a gun violence expert who maintains a database of indiscriminate mass shootings.

Trump is not the only one to suggest that improving mental health services could prevent mass shootings. Last year, President Obama said as much in a speech that recalled the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. Days after last month’s mass shooting in Las Vegas – the deadliest in US history – House Speaker Paul Ryan did the same.

It “perpetuates a stereotype of the mentally ill as dangerous,” says Dr. Fox, author of several books on mass shootings, including “Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder.”

That stigmatization may make it even more difficult for professionals to find the people who do need help.

“Suggesting that this is what people who have mental illnesses do likely means that if I’m someone with mental illness, I’m less likely to reach out and seek help,” says Arthur Evans Jr., chief executive officer of the American Psychological Association.

Staffing shortage

The ability to help is further hampered by a serious lack of resources and manpower, often leading to long wait lists for treatment. Two-thirds of Texas counties have no working psychiatrist, according to the Texas chapter of the National Association of Mental Illness (NAMI), a situation similar to other parts of the US.

And with more than half of mental-health providers aged 55 and older and nearing retirement, there are few people to take their place. Only 4 percent of US medical school graduates have been applying for residency training in psychiatry, according to a 2015 study.

These factors help explain why, according to NAMI, nearly 60 percent of adults with a mental illness don’t receive any mental-health services in a given year. That increases the risk that someone diagnosed with mentally illness may commit a violent act.

“If [someone] has a psychotic episode, they don’t have time to wait and get help, and that’s when violence happens,” says Sarah Feuerbacher, director of the Center for Family Counseling at Southern Methodist University in Plano, Texas.

There are some examples of state-level reforms. In November 2013, a mental-health facility in Virginia discharged Austin “Gus” Deeds because no psychiatric bed was available and he couldn’t be held in emergency custody for more than six hours. Less than 24 hours later, he attacked his father with a knife and committed suicide.

Six months later, the father – state Sen. Creigh Deeds – got a law passed reforming several elements of Virginia’s emergency mental-health system.

Back in Sutherland Springs, scene of the latest mass shooting, Eileen Anderson, who helps run the local historical museum, has been looking at her own family’s situation in a new light. Decades ago, her daughter was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and still sees a psychiatrist, takes medication, and, most important to her mother, continues to communicate with her.

“The love has kept us together, that’s the main thing,” she says. “With the things that happened to this guy [Kelley, the shooter], I mean it’s just carried over and over and over, until it just…”

Her voice trails off. “They need to love their family,” she says, after a while.