Virginia’s wake-up call: Democrats ignore rural voters at their peril

Loading...

| Dublin, Va.

Like most of rural America, southwest Virginia has become increasingly Republican in recent years. Former President Donald Trump has been widely credited with accelerating that trend, cranking up GOP turnout in rural counties across the country to win the White House in 2016.

Democrats have seen a growing edge in suburban and urban areas. Just last year, Joe Biden defeated Mr. Trump, and won Virginia by 10 percentage points, thanks in large part to strong support from suburbanites.

Why We Wrote This

Accepted wisdom among Democrats has been that demographics – more voters of color and more young voters – would lead to victory. Last week’s defeat in Virginia shows the danger of complacency.

But Republican Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin’s victory last week highlights a danger for the Democratic Party in this political realignment: The pool of potential GOP votes in rural America may be much bigger than either party realized. And although Mr. Trump helped supercharge that rural groundswell, it appears to be growing even in his absence from the national stage.

“For Democrats to be competitive in the midterms, they have to be able to compete for some of the rural vote," says Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson. “There are voters in these communities that Democrats can win – but people need to have a sense that Democrats value work and working people.”

Shortly after Glenn Youngkin secured the Virginia GOP’s gubernatorial nomination, Andy McCready, chair of the Pulaski County Republicans, says he got a call from some data specialists on the Youngkin campaign.

“They sent me a printout of my county and said, ‘A typical Republican turnout in your county is 7,100 voters. Do you think we could get 7,300 voters to come to the polls?’” recalls Mr. McCready over a lunch special at Fatz Cafe, a restaurant off Interstate 81. “And I said, ‘Absolutely.’”

The Youngkin campaign didn’t just meet that goal – they obliterated it. Last Tuesday, Pulaski, a rural, majority-white county in the southwest part of the state, supplied Mr. Youngkin with 9,631 votes.

Why We Wrote This

Accepted wisdom among Democrats has been that demographics – more voters of color and more young voters – would lead to victory. Last week’s defeat in Virginia shows the danger of complacency.

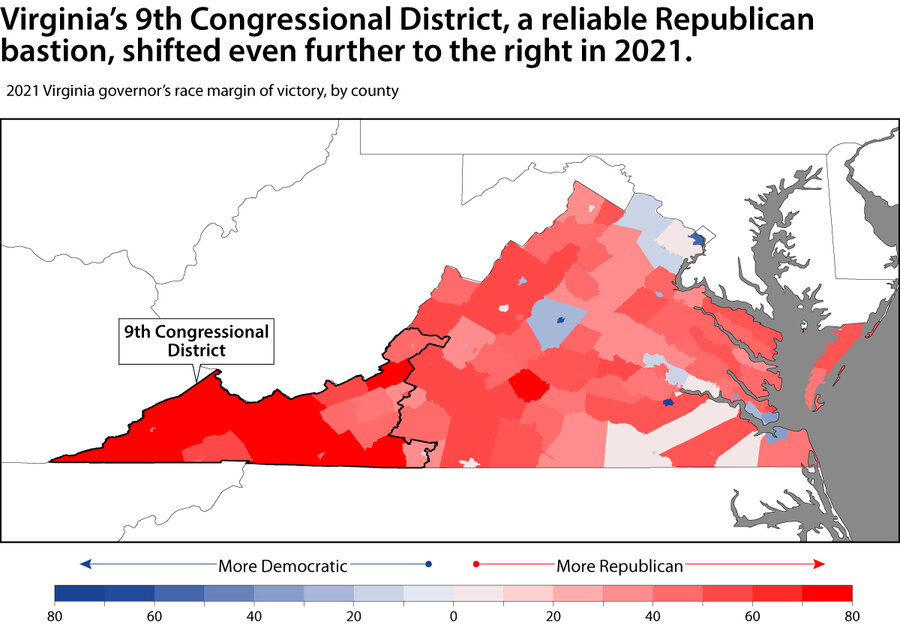

Like most of rural America, Virginia’s 9th Congressional District – a swath of mountains and farmland slightly larger than the state of New Jersey, and the poorest district in the state – has become increasingly Republican in recent years. Former President Donald Trump has been widely credited with accelerating that trend, cranking up GOP turnout in hundreds of Pulaskis across the country to win the White House in 2016.

On the flip side, Democrats have seen a growing edge in suburban and urban areas. In the “blue wave” of 2018, Democrats rode a tide of anti-Trump sentiment among educated voters to take control of the U.S. House of Representatives, including flipping three GOP-held seats in the Virginia suburbs. Just last year, President Joe Biden defeated Mr. Trump, and won Virginia by 10 percentage points, thanks in large part to strong support from suburbanites.

But Mr. Youngkin’s victory last week over former Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe highlights a danger for the Democratic Party in this political realignment: Namely, the pool of potential GOP votes in rural America may be much bigger than either party realized. And although Mr. Trump helped supercharge that rural groundswell, it appears to be growing even in his absence from the national stage. Mr. Youngkin actually surpassed the former president’s 2020 margins in every county in Virginia’s 9th district, running up the score a few thousand votes at a time.

Mr. Youngkin’s win can also be attributed to his success in the suburbs, where parental frustration over schools helped him cut into Mr. McAuliffe’s margins in the heavily populated counties outside of Washington D.C. He even flipped some suburban areas that had voted for Mr. Biden, such as Chesterfield and Virginia Beach.

But it’s the unexpectedly large rural turnout that has many Democratic strategists most worried ahead of next year’s midterm elections, when the party will be defending its razor-thin congressional majorities. It’s not that Democrats need to win in rural America to win overall, they note. But they can’t lose by those kinds of margins and remain competitive.

“There is a world of difference between losing a county 65 to 35 versus 80 to 20,” says Jesse Ferguson, who was deputy national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016 and has worked on a Virginia gubernatorial campaign. “For Democrats to be competitive in the midterms, they have to be able to compete for some of the rural vote."

“There are voters in these communities that Democrats can win – but people need to have a sense that Democrats value work and working people,” Mr. Ferguson adds.

Waiting on an “emerging Democratic majority”

In some ways, the Virginia results serve to undercut a theory on the left that demographic changes in the U.S. – particularly the growth of non-white populations and the progressive tilt of younger generations – would increasingly work to the Democratic Party’s advantage, eventually giving them an overwhelming advantage at the polls. Since the book “The Emerging Democratic Majority” was published in 2002, there has been a line of thinking among Democrats that they don’t actually need to appeal to rural voters, says Robert Saldin, a professor of political science at the University of Montana.

It’s possible demography will still favor Democrats in the long run. But in recent cycles, Republicans’ gains among white, working-class voters have arguably had a bigger impact – particularly since the Senate and Electoral College give disproportionate weight to underpopulated states.

“People have been waiting for this emerging Democratic majority for two decades,” says Mr. Saldin, author of the recent report “Gone Country: Why Democrats Need to Play in Rural America, and How They Can Do It Again.”

Southwest Virginia, like many rural areas, has actually has seen its population as a whole shrink. Of the 29 counties in the 9th district, all but five have lost residents over the past decade according to the U.S. Census, with several losing at least 10% of their population.

Likewise, there are almost 125,000 fewer registered voters in Virginia’s 9th district than in the 10th, which includes Fairfax and part of Loudoun County, just outside of the nation’s capital.

Yet Republicans are still finding plenty of room to grow.

Over the past year, Pulaski’s local GOP committee saw its numbers quintuple. The original group of 15 party stalwarts, which used to meet in a little room at the public library, had to relocate over the summer to a space that could hold more than 100 people.

Chip Craig, chair of the nearby Radford Republicans, has seen an even greater surge in growth. A small university town that was one of the last blue bubbles in southwest Virginia, Radford backed Mr. Biden in 2020, by 3,358 votes to 2,786. Last week, Mr. Youngkin won it 2,266 to 1,879.

“You have the disaster going on in Washington right now, and then you have McAuliffe going after parents and education,” says Mr. Craig, taking a break from cleaning up leaves in his yard, which is still dotted with campaign signs. “A lot of people out there felt disaffected and desperately wanted to do something.”

Much of the media coverage of the governor’s race focused on education as an issue impacting suburban voters. But the same concerns – school closures, mask mandates, and curriculum changes around race and identity – were powerful motivators for many rural voters as well.

Unhappiness with the Pulaski public school system led BJ Ratliff to pull her kindergartener out and enroll her in a private school. While she and her husband are having to work more to pay for their daughter’s education, she says it’s been worth it, adding that she knows two other local families who did the same thing.

“As bad as COVID-19 was, there were some hidden blessings. Parents began to see what the education system was teaching their children – and they didn’t like it,” says Republican state Sen. Travis Hackworth, who won a special election in Virginia’s 38th district with more than three-fourths of the vote earlier this year. “That goes for rural parents as well.”

“He looked us in the eye and listened”

In conversations with more than a dozen voters across southwest Virginia, many point to Mr. Trump as igniting their interest in politics and their enthusiasm for the GOP. Many still have questions about the integrity of the 2020 election, which the former president has continued to insist was stolen, despite all evidence to the contrary. And they express deep unhappiness with President Biden for “teaming up with progressives” in an effort to pass multi-trillion dollar legislation.

But they also give plaudits to Mr. Youngkin, saying he made them feel like their vote mattered.

“He looked us in the eye and listened,” says property manager Julie Muir, sharing an order of Cajun “firecracker stix” with her husband, Randy, at Fatz’s.

“We saw him so many times in this area,” adds Randy, who’s retired from a career in marketing. “He cared about getting 200 extra votes in Pulaski, 200 more in Lee, in Scott, and in Tazewell. I love it here in this ‘flyover type county,’ and I love the people here. But we are forgotten. We’re seen as small potato stuff.”

Mr. Craig says the Radford Republicans are taking some time off after months of door knocking, phone banking, and fundraising – and a celebratory dinner this Thursday. But then the planning will start for next year’s elections, says Mr. Craig, particularly three seats on the city council and three seats on the school board, for which he already has potential candidates.

“Now that they see we can win, I think we can get even more people registered,” says Mr. Craig. “People are motivated and ready to get after it.”