Virginia next in line to abolish death penalty. What’s behind the shift?

Loading...

| Richmond, Va.

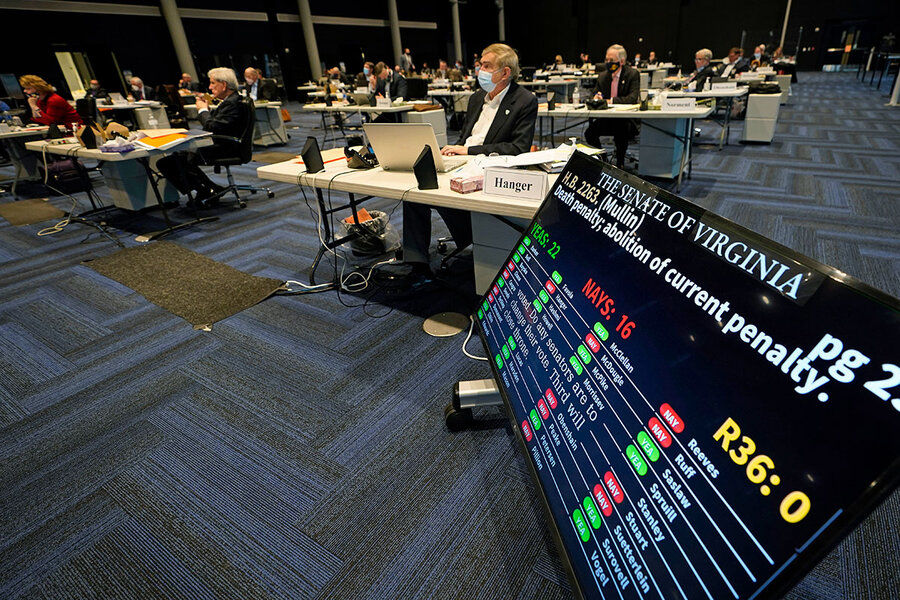

In early February, Virginia’s state legislature voted to abolish the death penalty – a significant change for a state that has executed more people than any other since its founding and is second only to Texas in executions since the late 1970s. Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam is expected to sign the abolition into law any day now, making Virginia the 23rd state to end the death penalty, and the first state to do so in the South, an area that far surpasses all other regions in executions.

Change on this issue has come swiftly: Virginia will be the 11th state to abolish capital punishment so far in the 21st century. And while Virginia’s move reflects a political transformation in the former Confederate capital, which has become more Democratic in recent years, the death penalty is also one of a host of issues, like LGBTQ rights and marijuana legalization, where there’s been a rapid shift in thought nationwide – driven largely by millennials.

“There has been a generational shift around views of marijuana, abolition of the death penalty, and acceptance of gay marriage,” says Delegate Mike Mullin, a Democrat who sponsored the Virginia House bill. “My generation, Republican or Democrat, have wanted a new way.”

Why We Wrote This

Public views on capital punishment are shifting rapidly, with more states moving to ban it. As with many issues, the change is being driven largely by millennials.

Rachel Sutphin wasn’t thinking about the death penalty when her father, Montgomery County Sheriff’s Deputy Cpl. Eric Sutphin, was killed on duty in Blacksburg, Virginia, in 2006. She was only 9, after all. Nor did she really understand it two years later, when a jury sentenced her father’s killer, William Morva, to death.

But as Mr. Morva’s lawyers periodically appealed the verdict over the next decade, his impending death became a recurring source of anxiety in Ms. Sutphin’s life. By the time she was in high school, Ms. Sutphin had begun writing letters to state legislators arguing against the death penalty. In 2017, when Mr. Morva’s appeals were exhausted and a date for execution was set, Ms. Sutphin started speaking out publicly and asked then-Gov. Terry McAuliffe for clemency, which he denied. Mr. Morva was killed by lethal injection later that year.

“To me, his death feels like an injustice in our [family’s search for] justice,” says Ms. Sutphin, who plans to become a pastor after graduating from Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia, in May. “We are going to kill this man for killing someone else, to prevent more killings?”

Why We Wrote This

Public views on capital punishment are shifting rapidly, with more states moving to ban it. As with many issues, the change is being driven largely by millennials.

In February, Virginia’s state legislature voted to abolish the death penalty – a significant change for a state that has executed more people than any other since its founding and is second only to Texas in executions since the late 1970s. Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam is expected to sign the abolition into law any day now, making Virginia the 23rd state to end the death penalty, and the first state to do so in the South, an area that far surpasses all other regions in executions.

The commonwealth’s move on this issue tracks with shifts in public opinion. A Gallup Poll from last fall found that 55% of Americans support the death penalty, down from a peak of 80% in the mid-1990s. And for the first time, a majority (60%) say life imprisonment without parole is a better punishment for murder than capital punishment.

Change on this issue has come swiftly: Virginia will be the 11th state to abolish capital punishment so far in the 21st century. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of death sentences imposed nationwide was less than half of what it was the decade before. And it is broad-based: Although Democrats are more likely to support life imprisonment without parole over the death penalty, the percentage of Republicans who feel the same way has increased 10 points in the past four years.

To be sure, Virginia’s move reflects a larger political transformation in the former Confederate capital, which has shifted from red to purple to blue in the past few decades. But the death penalty is also one of a host of issues, like LGBTQ rights and marijuana legalization, where there’s been a dramatic, and rapid, shift in thought nationwide – a shift driven largely by millennials.

“There has been a generational shift around views of marijuana, abolition of the death penalty, and acceptance of gay marriage,” says Delegate Mike Mullin, a Democrat who sponsored the Virginia House bill. “My generation, Republican or Democrat, have wanted a new way.”

A racial justice lens

According to Gallup, Americans between the ages of 18 and 34 are far less likely than their older peers to support the death penalty. Roughly one-quarter of millennials say they would support the death penalty over life imprisonment without parole, compared with 40% of older Americans.

But while public opinion has been shifting quickly, it didn’t happen automatically, say activists.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, which launched a five-year abolition plan in 2015. The group canvassed the state to find “unexpected or surprising allies,” says executive director Michael Stone, such as libertarians, Republican women, and faith leaders.

One of those faith leaders is the Rev. Dr. LaKeisha Cook, a justice reform organizer at the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy. She recently started advocating against the death penalty, holding prayer vigils at past lynching sites.

“Coming off of the summer, hearing the voices of Black Lives Matter, I think that we need to look at this fight against capital punishment specifically from a racial justice lens,” says Dr. Cook. “I’m so grateful to our legislators for not only recognizing our past, but putting us on the path toward reconciliation.”

A 1990 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that defendants who murdered white people were more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered Black people, and recent studies have come to similar conclusions. As Delegate Mullins points out, of the almost 1,400 people who have been put to death in Virginia since 1608, it wasn’t until 1997 that a white man was executed for killing a Black man. This racial aspect of capital punishment isn’t lost on millennials, he adds.

Death penalty opponents also point to fallibility (since 2000, there has been an average of four exonerations in the country per year), as well as cost. Because of the high costs associated with a capital trial and various appeals, lifetime incarceration costs a state less money than execution. Virginia is expected to save almost $4 million per year by abolishing the death penalty.

Capital cases can also be more taxing on the victims’ families, as Ms. Sutphin pointed out, since the trials typically last four times longer than non-capital trials. With his appeals, Mr. Morva’s trial lasted 11 years – which was relatively quick compared to most death penalty cases. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, convicts’ average time on death row is more than double that.

“Pro-life” and against capital punishment

Views of the death penalty have never been exactly split down party lines, with many conservatives opposing capital punishment on religious or moral grounds. Republicans in red states such as Wyoming, Kansas, Kentucky, Montana, and Missouri, for example, have recently sponsored legislation to abolish it.

Delegate Carrie Coyner, a Republican representing Chesterfield, Virginia, says she voted to end the state’s death penalty because she is “pro-life,” and believes that applies to both unborn babies as well as criminals who may have done “something heinous.” As a lawyer, Delegate Coyner knows what it feels like to lie awake at night wondering how she could have argued cases differently. She can’t imagine what that would be like with capital punishment on the table.

“We can all be better than we are today,” says Ms. Coyner. “I have a hard time reconciling that idea [with] the state stepping in and choosing to determine that we are going to kill someone.”

Still, Ms. Coyner was one of only three House Republicans who ultimately voted in favor of the bill. And despite some initial Republican support in the upper chamber, no Senate Republicans signed on.

Supporters argue the death penalty is a just punishment for murder. Many add that even if a convicted person is sentenced to life imprisonment without parole, execution is the only way to absolutely ensure the perpetrator will never be on the street again – and to give victims’ families closure. Some also believe capital punishment is a deterrent, though opponents point out that states with death penalty laws don’t have lower crime rates than those without.

Yet execution isn’t necessarily the justice that all victims’ families want, says Ms. Sutphin.

“There’s a common misconception that all murder victims’ families want the death penalty, and once they’re given the death penalty, everything is OK,” says Ms. Sutphin. “But now I just have more dates of death to remember: my father’s and Morva’s.”