‘Texodus’: Why the Lone Star State might turn blue for real this time

Loading...

| Fort Worth, Texas

As Texas moves slowly but inevitably into majority-minority status, it’s become something of a biennial tradition to ask if the next election will finally mark the end of decades of Republican dominance in the state.

But next year could, as the saying goes, be the year.

Why We Wrote This

At the Monitor Breakfast, GOP Sen. Ted Cruz predicted Texas will be “hotly contested” in 2020, thanks to the growing clout of suburban voters – particularly women – who have been moving to the left, politically.

Lately, a rash of congressional Republicans opting not to run for reelection – a phenomenon some are calling the “Texodus” – has fueled Democrats’ excitement. And to understand why Texas politics is shifting, many say, you shouldn’t just look at the state’s growing Hispanic population. You should look at where those GOP retirements are happening: around the booming, increasingly liberal cities.

“The two broad demographic trends that are occurring nationally are: number one, blue-collar working-class voters are becoming more conservative. That is turning Midwestern states more Republican,” GOP Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas told reporters at the Monitor Breakfast on Thursday. At the same time, “suburban voters – in particular suburban women – have been moving left. That’s turning states with big suburban populations – states like Texas, states like Georgia, states like Arizona – much more purple.”

“If we lose Texas,” he adds, “it’s game over.”

In the run-up to the 2008 election, when Brandy Derrick was first becoming politically aware, she joined millions of Texans in voting to reject Democratic nominee Barack Obama. Former GOP Sen. John McCain carried Tarrant County, where she lives, by double digits.

He won Texas by a similar margin, but Tarrant, which includes the city of Fort Worth and its suburbs, was the only urban county he won. Three other major metropolitan counties – Bexar (San Antonio), Dallas, and Harris (Houston) – flipped that year to join Travis County (Austin) in voting Democratic, and they haven’t flipped back since.

Last year, Tarrant County joined them, voting for a statewide Democrat – U.S. Senate candidate Beto O’Rourke – for the first time since 1990. Ms. Derrick, owner of Legal Ease Bookkeeping in Fort Worth, was not surprised.

Why We Wrote This

At the Monitor Breakfast, GOP Sen. Ted Cruz predicted Texas will be “hotly contested” in 2020, thanks to the growing clout of suburban voters – particularly women – who have been moving to the left, politically.

“I think Texas as a whole is moving that way,” she says.

Democrats certainly hope so – but then, they’ve been hoping so for a while. With Texas slowly but inevitably moving into majority-minority status, it’s become something of a biennial tradition in the Lone Star State to ask if the next election will finally mark the end of decades of Republican dominance.

Every dawn has been false. Last year, Sen. Ted Cruz beat Mr. O’Rourke despite becoming the first top-of-the-ticket Republican to lose in all of the major Texas metro areas since Barry Goldwater in 1964. But next year could, as the saying goes, be the year. While no Democrat won statewide in 2018, in terms of turnout and down-ballot races the party had its best election in decades.

Lately, a rash of congressional Republicans opting not to run for reelection – a phenomenon some are calling the “Texodus” – has only fueled Democrats’ excitement. And to understand why Texas politics is shifting, many say, you shouldn’t just look at the state’s growing Hispanic population. You should look at where those GOP retirements are happening: around the booming, increasingly liberal cities.

“The two broad demographic trends that are occurring nationally are: number one, blue-collar working-class voters are becoming more conservative. That is turning Midwestern states more Republican,” Senator Cruz told reporters at the Monitor Breakfast on Thursday. At the same time, “suburban voters – in particular suburban women – have been moving left. That’s turning states with big suburban populations – states like Texas, states like Georgia, states like Arizona – much more purple.”

“If we lose Texas,” he adds, “it’s game over.”

An urban-suburban boom

As measured by job creation and population growth, the “Texas Triangle” bounded by Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio-Austin is the strongest economic region in the United States. While Houston is the hub of the U.S. energy industry, big tech companies are settling in Austin (Google and Apple) and Dallas (Uber).

And with a large, young, and college-educated workforce flocking to live and work in the region, these Texas cities and suburbs have been both gaining political power and becoming more solidly liberal. Research by Renée Cross and Richard Murray at the University of Houston has found that voters in the 27 counties around big metro areas grew from 52% of the total electorate in 1968 to 69% in 2018. Meanwhile, voters in the more rural counties – outside the Democratic strongholds in south Texas – decreased from 38% to 8% in that time.

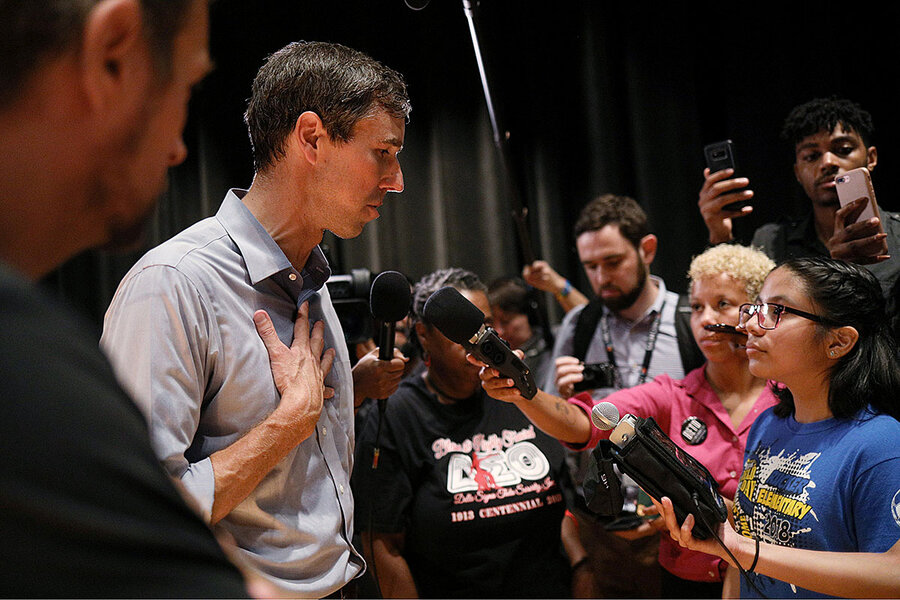

Mr. O’Rourke in particular was effective in ginning up support and – crucially, for a low-turnout demographic – votes from young Texans. He carried the state’s five major urban counties by a combined 790,000 votes last year, six times more than Mr. Obama in 2012. Registering and turning out more voters in those cities and suburbs is at the core of Texas Democrats’ plan, released this week, to flip “the biggest battleground state in the country.”

The “Texodus” suggests that Republicans in the state may have the same concerns. Four of the five congressmen who will be stepping down next year represent suburban districts that have become increasingly competitive; the fifth, Rep. Will Hurd, represents a vast border district that is the most competitive in the state.

“The people [Texas] is attracting, the job opportunities, are magnets for younger voters, voters who are perhaps more liberal,” says Ann Bowman, a political scientist at Texas A&M University. “The Beto effect was mobilizing younger voters,” she adds. “Are we going to see that in 2020? The general trend is for younger voters to turn out less.”

An unpopular president

What could boost Democratic turnout is the Republican ticket being led by one of the most unpopular presidents in recent memory. Just 45% of registered voters in Texas approve of President Trump, while 50% don’t, according to a poll this week from Quinnipiac University. He trailed most of his Democratic challengers head-to-head in the state in a recent University of Texas at Tyler survey.

Mr. Trump’s often harsh and divisive rhetoric “trumps anything he’s doing with the economy for many suburban women,” says Nancy Bocskor, director of the Center for Women in Politics and Public Policy at Texas Woman’s University in Denton.

“Suburban women are going to turn out and vote,” she adds. “That’s a bigger wild card here than the growing number of Hispanic voters.”

Decades of political dominance in Texas could also now be making life more difficult for Republicans.

As in states around the country, a lack of competitive general elections has led to competitive primaries, with Republicans drifting further and further to the right since former President George W. Bush built his presidential campaign on “compassionate conservatism” and his ability to work with Democrats while governor of Texas. This in turn has alienated moderate voters, including in suburbs that used to be conservative strongholds.

“If all you’re doing as a political party is communicating with your primary voters, that’s a great way to perhaps win the next election, but what it is not is a way to grow your party,” says Harold Cook, a longtime Democratic strategist in Texas.

Republicans in the state legislature responded to that head-on in the legislative session earlier this year, avoiding the polarizing cultural issues like the failed “bathroom bill” that had marked the 2017 session in favor of pocketbook issues like property tax and public education reform. Whether those efforts generated enough goodwill to help Republicans 13 months from now remains to be seen.

“I think a lot of these legislators made very smart moves to help shore up that Republican brand,” says Professor Bocskor. “They were spot on in targeting what suburban women are concerned about.”

Yet right now, “the biggest issues are health care and immigration and gun control,” says Brandon Rottinghaus, a political scientist at the University of Houston. “Those are all issues that break badly for Republicans in terms of support from suburban women.”

“We’re not there yet”

Thirteen years after they traded Northern California for North Texas, Melissa and Mike Patruso are beginning to feel more at home – politically, at least – in Watauga, a suburb north of Fort Worth.

“How well Beto did in the election last year – that was surprising,” says Mrs. Patruso, “and good.”

So could 2020 be the year? Will Texas turn blue?

“I don’t think so just yet,” she says. “We’re not there yet.”

Most experts agree that Democrats’ 18-year streak of not winning a statewide race in Texas will probably continue into 2022. Mr. Trump will likely turn out voters who support him as much as he will voters who reject him, and fear of Republicans losing Texas – and its huge cache of 38 electoral votes – could also motivate conservative voters.

Democrats further down the ballot will face a new hurdle next year, with straight-ticket balloting eliminated by the state legislature after the 2018 election. And unlike that election, Republicans in Texas now know they’re in for a fight.

“Democrats won’t be able to take them by surprise this time,” says Mr. Cook, the Democratic strategist. “There’s only one way to run in an atmosphere like this, and that’s to run scared.”

“Texas is going to be hotly contested,” agrees Senator Cruz. “We will see, I believe, record-setting – in fact, record-shattering – Democratic turnout in 2020, because the far-left is pissed off. They hate the president, and that is a powerful motivator.” For Republicans, he adds, the key will be “to turn everybody else out. If the left shows up in massive numbers, and everybody else doesn’t, that’s how we end up with an incredibly damaging election.”