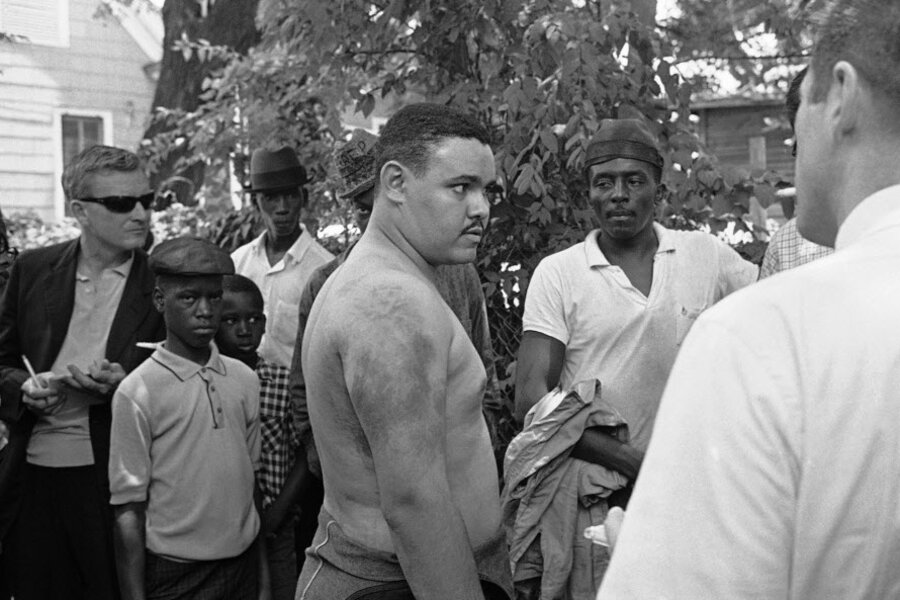

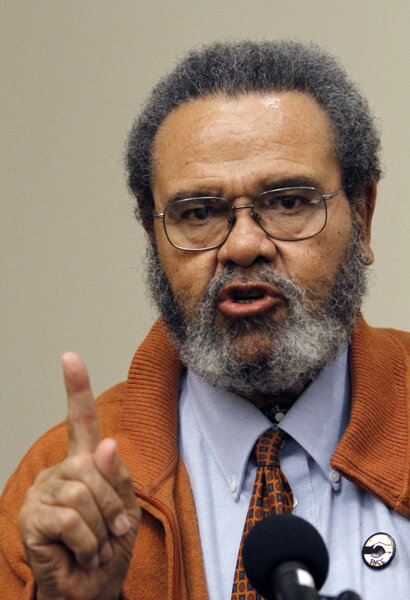

Lawrence Guyot, civil rights leader, dies after decades of activism

Loading...

| Washington

Lawrence Guyot, a civil rights leader who survived jailhouse beatings in the Deep South in the 1960s and went on to encourage generations to get involved, has died. He was 73.

Guyot had a history of heart problems and suffered from diabetes, and died at home in Mount Rainier, Md., his daughter Julie Guyot-Diangone said late Saturday. She said he died sometime Thursday night; other media reported he passed away Friday.

A Mississippi native, Guyot (pronounced GHEE-ott) worked for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and served as director of the 1964 Freedom Summer Project, which brought thousands of young people to the state to register blacks to vote despite a history of violence and intimidation by authorities. He also chaired the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought to have blacks included among the state's delegates to the 1964 Democratic National Convention. The bid was rejected, but another civil rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer, addressed the convention during a nationally televised appearance.

Guyot was severely beaten several times, including at the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary known as Parchman Farm. He continued to speak on voting rights until his death, including encouraging people to cast ballots for President Barack Obama.

"He was a civil rights field worker right up to the end," Guyot-Diangone said.

Guyot participated in the 40th anniversary of the Freedom Summer Project to make sure a new generation could learn about the civil rights movement.

"There is nothing like having risked your life with people over something immensely important to you," he told The Clarion-Ledger in 2004. "As Churchill said, there's nothing more exhilarating than to have been shot at — and missed."

His daughter said she recently saw him on a bus encouraging people to register to vote and asking about their political views. She said he was an early backer of gay marriage, noting that when he married a white woman, interracial marriage was illegal in some states. He met his wife Monica while they both worked for racial equality.

"He followed justice," his daughter said. "He followed what was consistent with his values, not what was fashionable. He just pushed people along with him."

Susan Glisson, executive director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi, called Guyot "a towering figure, a real warrior for freedom and justice."

"He loved to mentor young people. That's how I met him," she said.

When she attended Ole Miss, students reached out to civil rights activists and Guyot responded.

"He was very opinionated," she said. "But always — he always backed up his opinions with detailed facts. He always pushed you to think more deeply and to be more strategic. It could be long days of debate about the way forward. But once the path was set, there was nobody more committed to the path."

Glisson said Guyot's efforts helped lay the groundwork for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

"Mississippi has more black elected officials than any other state in the country, and that's a direct tribute to his work," she said.

Guyot was born in Pass Christian, Miss., on July 17, 1939. He became active in civil rights while attending Tougaloo College in Mississippi, and graduated in 1963. Guyotreceived a law degree in 1971 from Rutgers University, and then moved to Washington, where he worked to elect fellow Mississippian and civil rights activist Marion Barry as mayor in 1978.

"When he came to Washington, he continued his revolutionary zeal," Barry told The Washington Post on Friday. "He was always busy working for the people."

Guyot worked for the District of Columbia government in various capacities and as a neighborhood advisory commissioner.

D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton told The Post in 2007 that she first met Guyot within days of his beating at a jail in Winona, Miss. "Because of Larry Guyot, I understood what it meant to live with terror and to walk straight into it," she told the newspaper. On Friday, she called Guyot "an unsung hero" of the civil rights movement.

"Very few Mississippians were willing to risk their lives at that time," she said. "But Guyot did."

In recent months, his daughter said he was concerned about what he said were Republican efforts to limit access to the polls. As his health was failing, he voted early because he wanted to make sure his vote was counted, he told the AFRO newspaper.

Funeral services are pending.