A history of American thought on abortion: It’s not what you think

Loading...

| New York

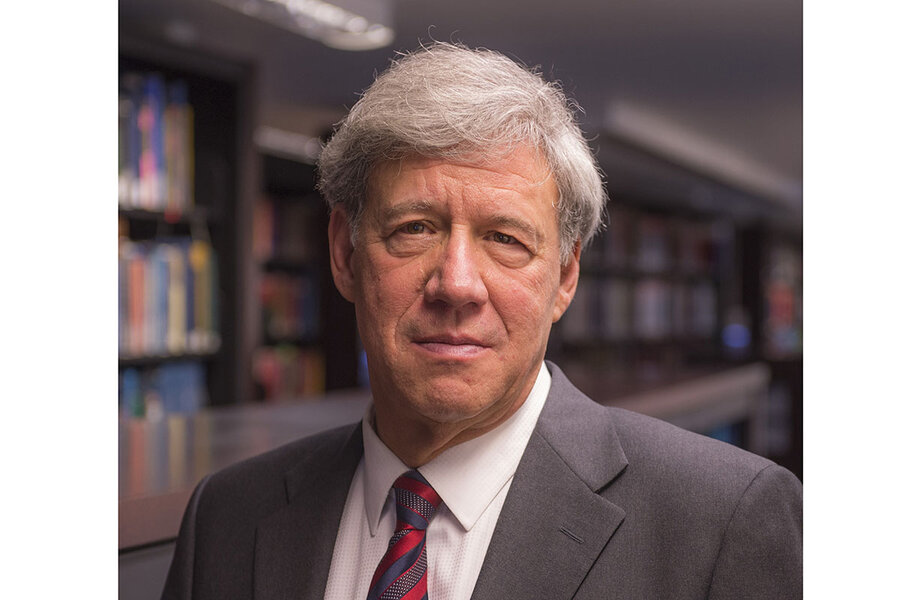

In a 6-3 majority ruling on Friday, the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision giving women the right to abortion. In anticipation of the ruling last week, the Monitor interviewed Geoffrey R. Stone, author of the legal history “Sex and the Constitution,” who says the history of abortion in the United States is more complicated than many people realize. [Note: this interview was conducted before the Supreme Court struck down Roe.]

At the time of the Roe v. Wade ruling, almost all Americans believed that abortion had always been illegal, says Professor Stone, who teaches law at the University of Chicago. Further, he adds: “No one would have imagined that abortion was legal in every state at the time the Constitution was adopted, and it was fairly common.”

Why We Wrote This

The road to Roe – and beyond – includes an evolution of American values often overlooked in the heat of the moment. Few know abortion was legal and common when the Constitution was written, a legal historian explains.

A new ban on abortion would not be out of line with past ebbs and flows on the issue of abortion, including evolving religious trends, the move from agrarian to urban lifestyles, immigration, and even the gender politics of the medical profession. By the end of the 19th century, U.S. states banned abortion, except to save the life of a mother, as well as contraception. By the 1960s, however, the court began to recognize a right to privacy when it came to such reproductive decisions.

Professor Stone sees a crisis of credibility for the court now that it has struck down Roe: “The majority of people still believe there should be a right to abortion and a right to privacy, and most don’t read or hear all that much from Evangelicals, Catholics, or from strongly anti-abortion people. I think the vast majority ... will be really angry.”

In a 6-3 majority ruling on Friday, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision giving women the right to abortion. In anticipation of the ruling last week, the Monitor interviewed Geoffrey R. Stone, author of the legal history “Sex and the Constitution.”

The history of abortion in the United States is more complicated than many people realize, says Professor Stone, who teaches law at the University of Chicago. Government regulation of abortion has long been connected to the nation’s religious history, caught in the ebbs and flows of evolving cultural mores that also resulted in national prohibitions against contraception, private sexual behavior, and obscenity.

[Note: this interview was conducted before the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade.]

Why We Wrote This

The road to Roe – and beyond – includes an evolution of American values often overlooked in the heat of the moment. Few know abortion was legal and common when the Constitution was written, a legal historian explains.

What made you decide to delve into questions about sex and the Constitution and the regulatory history of abortion?

I was a law clerk for Justice [William R.] Brennan on the Supreme Court when Roe was decided [in 1973], and I was intrigued by the fact that the court during that era had not only adopted a Constitutional right to contraception and a right to abortion, but later a right of gay people to engage in sexual behavior and then a right of gay people to marry. So, I was curious how did this all come about?

Americans, almost all, believed at that time that abortion had always been illegal, that it had always been criminal. And no one would have imagined that abortion was legal in every state at the time the Constitution was adopted, and it was fairly common. But people didn’t know that.

The justices came to understand the history of abortion partly because [Justice Harry] Blackmun previously had been general counsel [at the Mayo Clinic] and researched all this stuff. But this history also began to be put forth by the women’s movement. And this was eye-opening to the justices, because they had, I’m sure every one of them, assumed abortion had been illegal back to the beginning of Christianity. And they were just shocked to realize that was not the case, and that prohibiting abortion was impairing what the framers thought to be ... a woman’s “fundamental interest.”

Did you have the same assumptions about abortion at the time?

What weighed on me most was that, in the past, women could never speak out about their illegal abortions because it was a crime – even speaking about it in public was considered obscenity. So there was no public story about these things happening, except in instances when somebody died having an abortion.

But the public had no concept of how many women were having abortions or the horror they were living in. And that began to change when women began to speak out about what their experience had been. And that came into the minds of the justices. And I think those are the two factors that most influenced more conservative justices to embrace [abortion as a fundamental right], including conservative justices appointed by [President Richard] Nixon.

Abortion was legal in every state when the Constitution was adopted?

In the 18th century, abortion was completely legal before what was called the “quickening” of a fetus – when a woman could first feel fetal movement, or roughly four and a half months through a pregnancy. No state prohibited it, and it was common. Post-quickening, about half the states prohibited abortion at the time the Constitution was adopted. But even post-quickening, very few people were ever prosecuted for getting an abortion or performing an abortion in the founding era.

So much of your book is about religion – especially religion in America. What role did religion play as states began to outlaw abortion?

During the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century through the 1840s, individuals with strongly held religious views came to believe that the nation was moving in ways they thought were immoral. For example, when the Constitution was adopted, there were no laws against obscenity. Evangelical ministers called for a number of morals-based laws like Sunday closing laws, blasphemy prosecutions, temperance laws.

The idea that life began at conception was originally a Catholic notion, but Protestants tended to disagree with that. During the Second Great Awakening, however, the idea of being “born again” started to make many believe life began at conception, in an instant, just like at the moment of conversion, and that really captured the views of a large percentage of American Protestants. It was at this time that people began to refer to this as a “Christian nation” – an era in which a substantial percentage of the American people fiercely believed this.

How did the American Medical Association influence the eventual total ban of abortion?

Partly as a result of the attitudes of the Second Great Awakening, the American Medical Association, which had just been created in the 1840s, took the view that the fetus was a person from conception. Some leaders of the fledgling organization were fiercely religiously grounded. And there’s a lot of skepticism about why they did that. One of the explanations is that they were also trying to put midwives out of business. They wanted to take over that part of the process of giving birth. So that also made a significant impact, because it was the first time that medical officials were saying that abortion from the moment of conception is killing a person.

But the message was also that women should not be trusted. One of their themes was that, when women are pregnant, they simply do not have judgment. They also made the argument that children born after a woman had an abortion suffered, because abortion would make subsequent children deranged in certain ways. All of this created the background foundation for the Comstock Laws, which banned contraception, as well as any kind of discussion about anything to do with sex. That’s why well into the 1950s, you couldn’t show a married couple in bed together on television. And it was astonishing that every state banned obscenity, every state banned abortion, and every state banned contraception. And the federal government did the same, changing and eliminating what was the case at the time of the framing of the Constitution, and basically making anything relating to sex illegal.

How did history shift away from these ideas about obscenity, sex, and reproduction?

People were moving beyond the idea of imposing deeply religious views on everybody else. Immigration helped change this in the early 20th century, because there were a lot of people who came to the country who didn’t share those views.

But it changed mainly because people understood that you don’t want to cause people to have unwanted pregnancies. It used to be the case that a large number of children were important to families when they were all living on farms, because you needed the kids to do the work. But as everybody was moving into urban areas, you didn’t want as many kids. So not allowing contraception was causing families to have many more children than they realistically wanted, and so that’s why most of the states began to legalize it.

You write that the 1965 Supreme Court case Griswold v. Connecticut, which threw out state bans of contraception, was “groundbreaking” and “daring.” What made this decision so important?

One thing to understand is that the Bill of Rights included the Ninth Amendment, which provides that the enumeration of certain rights in the Constitution shall not be taken to deny or disparage other rights. And second, they basically understood majorities would not be fair to people without power, whether it was religious minorities or racial minorities or women. The framers understood the problem with democracy was that it’s controlled by majorities. And we want a society where everybody has rights, [and everyone is] protected. It’s the natural inclination of majorities to disregard the rights of others, and we want the Bill of Rights to prevent them from doing that.

The issue in Griswold was whether the state should have the power to prohibit married couples from making fundamental decisions about themselves, to be able to engage in sex without running the risk of having unwanted children. The court here said that the Ninth Amendment guaranteed the “privacies of life,” and that the privacies of the marriage relationship were part of “right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights.”

[The Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.] Is the pendulum shifting back to a more religious understanding of the meaning of abortion?

The majority of people still believe there should be a right to abortion and a right to privacy, and most don’t read or hear all that much from evangelicals, Catholics, or from strongly anti-abortion people. I think the vast majority will think this is a horrible decision, and they will be really angry. It will also undermine the court’s credibility with society, because historically, when the court recognized rights that previously hadn’t been recognized, it was to protect individuals who were otherwise powerless. So overturning Roe will be close to unprecedented in taking away a right meant to protect individuals and doing so in a dramatic and aggressive way.