The one case that could define the Supreme Court’s term – and legacy

Loading...

The Supreme Court opens its term Monday at a fraught moment: Public approval of the institution has dropped below 50% for the first time in decades, according to recent polls. And after a few years marked by relatively slow change in some contentious areas of the law – but significant changes in the court’s personnel – this term could upend the way several cultural wars are fought after decades of established rules.

The court is likely to tackle weighty policy issues, such as vaccination mandates and changes to state election laws. But unlike any recent year, there is one case above all, in the eyes of the public at least, that will define the court’s term, and perhaps its legacy: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health.

Why We Wrote This

Is the law really the law, if changes in personnel result in dramatic change? That’s the question Americans are grappling with as a momentous Supreme Court term opens this week.

“This all rises and falls on Dobbs,” said Jeffrey Wall, a former acting solicitor general under President Donald Trump, during a preview of the upcoming term held by the Georgetown Supreme Court Institute last month.

In the case of Dobbs, the question is whether the court as an institution can weather the damage of transforming abortion law in the U.S., given that a majority of Americans favor some abortion rights and generations of women have grown up expecting a constitutional right to bodily autonomy.

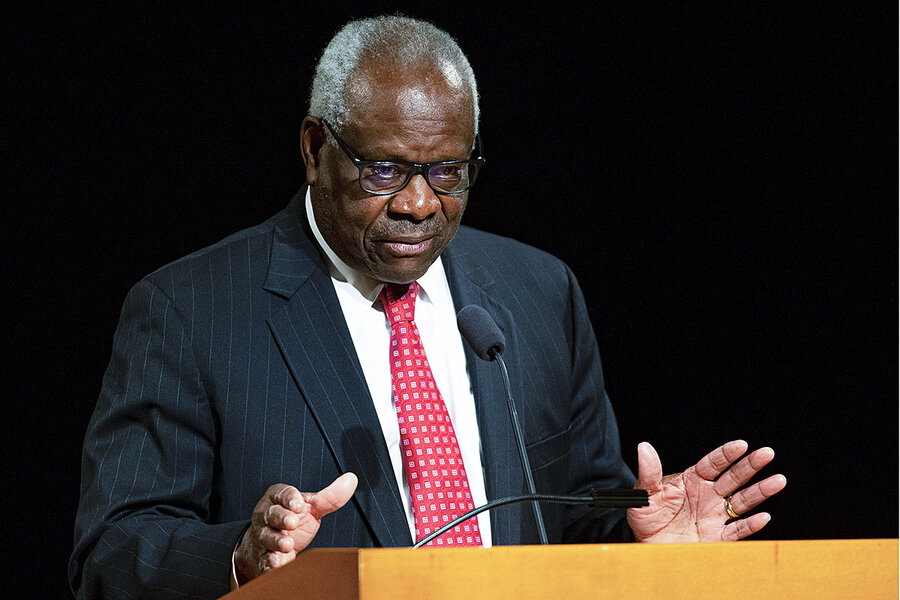

Justice Clarence Thomas, now the most senior member of the United States Supreme Court, admits he’s never been one to regularly hype the court.

“I’m quite content not to get out on the road,” he said last month, recalling a conversation years ago when his late colleague Justice Antonin Scalia encouraged him to get out “and fly the flag.”

It was a lighthearted anecdote to open a rare public appearance by Justice Thomas, at the University of Notre Dame. But he is one of four justices who has been out flying the high court’s flag recently. And they have all delivered a consistent message: The court is an independent body that serves the entire country, making its decisions without regard for political preferences.

Why We Wrote This

Is the law really the law, if changes in personnel result in dramatic change? That’s the question Americans are grappling with as a momentous Supreme Court term opens this week.

“Knowing all the disagreements” on the court, said Justice Thomas, “it works.”

“It’s flawed, but I will defend it,” he added. “We should be careful destroying our institutions because they don’t give us what we want when we want it.”

The statements have been appearing at a fraught moment for the court. As the justices prepare for a new term, which begins this week, public approval of the institution has dropped below 50% for the first time in decades, according to recent polls. And after a few years marked by relatively slow, incremental change in some contentious areas of the law – but significant changes in the court’s personnel, cementing a six-justice conservative supermajority – this term could upend the way several cultural wars are fought after decades of established rules.

The court is likely to tackle weighty policy issues as well, such as vaccination mandates and changes to state election laws. But unlike any recent year, there is one case above all, in the eyes of the public at least, that will define the court’s term, and perhaps its legacy: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health.

“This all rises and falls on Dobbs,” said Jeffrey Wall, a former acting solicitor general under President Donald Trump, during a preview of the upcoming term held by the Georgetown Supreme Court Institute last month.

With respect to the court’s legitimacy, he added, “I don’t think there will be a groundswell among the public unless there’s a major ruling on abortion.”

For the public, however, “the relationship between partisan politics and the court has been cast into particularly stark focus in the past few years,” says Aziz Huq, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School.

Since Republicans mobilized five years ago to block Merrick Garland’s nomination to the high court by President Barack Obama – a campaign that attracted millions of dollars in support from political, mostly conservative, interest groups – three new justices have joined the court, all nominated by President Trump and confirmed in party-line votes.

“The court has been the focus of partisan mobilization in quite explicit ways,” says Professor Huq. And “the change in the composition of the court has led to dramatic changes in jurisprudence.”

Dobbs could soon be the latest example.

A term defined by a single case?

For decades, the high court has been cautious in reviewing its abortion precedents. The Mississippi law at issue in Dobbs bans most abortions after 15 weeks, and the justices spent over seven months deciding whether to review it.

The law has been struck down by lower courts, citing Supreme Court precedent guaranteeing a woman’s right to abortion pre-viability – considered to be around 24 weeks – as established in Roe v. Wade in 1973.

The justices are focused on the weightiest question posed to them: whether all bans on pre-viability abortions are unconstitutional.

That question doesn’t specifically name the court’s landmark abortion precedents – Roe and 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey – but in its brief Mississippi argues that both should be overturned, calling them “egregiously wrong.” (In its petition to the court a year earlier, it argued the case was an “opportunity to reconcile” those precedents with new understandings of viability.) In that sense, Dobbs is the most direct threat to the right to abortion the court has heard in a generation.

The “basic rule” from those decisions “was no pre-viability bans,” says Elizabeth Sepper, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, “and Mississippi has passed a pre-viability ban.”

“If they uphold Mississippi’s law,” she adds, “they will have effectively reversed Roe v. Wade, even if they don’t say the words.”

Federal courts have enabled the gradual restriction of abortion access, permitting state regulations like mandatory waiting periods, parental notification requirements, and required counseling. More restrictions have been enacted in the first six months of this year than in any year since Roe, reported the Guttmacher Institute, a research organization that supports abortion access.

But the Supreme Court has still upheld the core right to abortion, always with a conservative justice joining his liberal colleagues. In a 5-3 ruling in 2016, Justice Anthony Kennedy joined the majority in striking down a Texas abortion regulation, with Chief Justice John Roberts dissenting. Then, last year, Chief Justice Roberts voted to strike down a Louisiana law almost identical to the Texas one – though he emphasized that, while he was now bound by the 2016 ruling, he still disagreed with it.

Thus, when the court holds oral argument in Dobbs in December, Chief Justice Roberts will be watched closest, most experts agree.

If he’s in the majority, he decides who writes the opinion, “and with that power he can assign narrower-crafted opinions,” says Professor Huq.

Enough of his colleagues have been attracted to these narrower opinions in the past to form a majority, note court watchers, including in high-profile cases last term on religious liberty and the Affordable Care Act.

“There is now a six-justice majority to overrule Roe,” adds Professor Huq, “but there’s differences over timing and pace and the way of achieving that.”

Gun rights, death penalty also on docket

Dobbs will not be the only significant case the justices hear this term.

For over a decade the court had avoided hearing a gun rights case, but in November the court will hear a challenge to a New York restriction on concealed carry permits that could see gun restrictions loosened nationwide. October and November will also bring major cases on death penalty jurisprudence – including an appeal from Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev – and state funding for religious schools.

Yet for this term, the court still only has 41 cases on its merits docket – the cases that are heard in full during the year – according to SCOTUSblog. While it has issued its smallest number of merits decisions since the Civil War in the past two terms – 56 and 53, respectively – there could still be some major petitions taken up for next year. (The justices are currently deciding whether to hear a challenge to Harvard University’s affirmative action policy, for example.)

And all that doesn’t even account for actions the court could take on its increasingly busy “shadow docket” – petitions the justices decide on an emergency basis with limited briefing and no oral argument. High-profile issues like vaccine mandates and changes to state voting laws could all end up before the justices, either on the merits or shadow dockets, before the term ends next summer.

Indeed, it was a controversial month of shadow docket activity that preceded the justices’ public reassurances about the court’s institutional integrity. In quick succession this summer, the court issued brief orders that halted the federal government’s pandemic-related eviction moratorium, required the Biden administration to reinstate a Trump-era immigration policy, and allowed a Texas law effectively banning abortion in the state to remain in effect pending appeals.

Judicial philosophies versus partisan politics

Justice Stephen Breyer, in interviews last month while promoting his new book, called the court’s Texas abortion decision “very, very, very wrong.” But the Clinton appointee – and oldest member of the high court – has also defended his colleagues as responsible jurists who decide cases based on judicial philosophies, not partisan affiliations.

“There are many jurisprudential differences” on the court, Justice Breyer told CNN last month. “It isn’t really right to say that it’s political in the ordinary sense of politics.”

A week earlier, the court’s newest member, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, made a similar claim in a speech in Louisville, Kentucky. The high court isn’t “a bunch of partisan hacks,” she said at an event for Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, the Louisville Courier Journal reported. “Judicial philosophies are not the same as political parties.”

Others skeptical that the court has become politicized point to recent high-profile rulings where the court bucked expectations of conservative victories, such as when it upheld “Obamacare” last year and voted to not shield President Trump’s tax returns.

“None of those things came to pass,” said Roman Martinez, a lawyer at Latham & Watkins and a former clerk for Chief Justice Roberts and then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh, at the Georgetown Law event.

“If you talk to people on the right,” he added, “you will see a lot of frustration with the court, that they haven’t acted in a way the politics would suggest.”

Whether this term will yield similar surprises remains to be seen, but one member of the court’s liberal wing recently voiced her own frustrations at decisions the court reaches.

“There is going to be a lot of disappointment in the law, a huge amount,” said Justice Sonia Sotomayor last week, at an event hosted by the American Bar Association. “Look at me. Look at my dissents.”

A frequent dissenter to the court’s conservative opinions, she added that they help her “explain how I feel.” But other justices prefer different approaches, she explained, such as Justice Elena Kagan, another member of the court’s liberal wing.

“Justice Kagan believes that the best way to influence the majority is to try to narrow their holdings, to try to figure out how to keep the impact of a holding as narrow as possible,” said Justice Sotomayor.

That way, she continued, there will be a pathway later to “change the direction of a bad ruling.”

In the case of Dobbs, the question is whether the court as an institution can weather the damage of transforming abortion law in the U.S., given that a majority of Americans favor some abortion rights and several generations of women have grown up expecting a constitutional right to bodily autonomy. For the term as a whole, the overarching question is whether narrow rulings are possible after the court has chosen to confront major constitutional questions they have reinforced – or, in the case of gun rights, avoided – for decades.

“The court’s legitimacy rests on showing the public that a change in personnel doesn’t mean a dramatic change of law,” said Farah Peterson, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School and a former clerk for Justice Breyer, during a preview event in September.

“That’s what’s at stake in this term.”