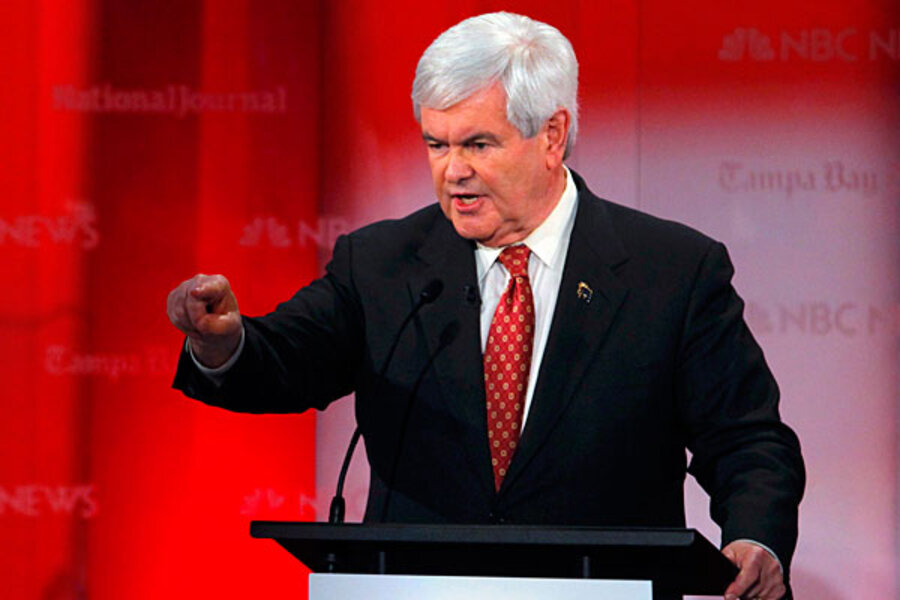

“It’s been pointed out that in every single count, I was exonerated… After the case, a federal judge, the Federal Election Commission, and the Internal Revenue Service, all three, exonerated me.” – Newt Gingrich on CNN, Jan. 22, 2012

When asked about his 1997 reprimand, Gingrich has responded with a variation of this comment to CNN. But the cited examples – IRS, FEC, and a federal judge – all involved either tax law or election law, not the rules of ethical conduct enforced by the House Ethics Committee.

Gingrich is comparing apples and oranges.

The former speaker’s claim of vindication is accurate in the sense that many of Gingrich’s political opponents had accused him of tax fraud and that an Internal Revenue Service investigation in 1999 concluded there was no tax fraud.

But the Ethics Committee did not render a legal verdict on whether Gingrich violated tax laws. Instead, the committee condemned Gingrich for using poor judgment in his conduct, and particularly in not seeking the advice of a tax lawyer.

That is not a question of legality or criminality; it relates to a different standard, a standard of rules and ethical requirements set and enforced by the House of Representatives.

As speaker of the House, Gingrich was subject to the same standard of conduct as every other member of Congress. His statements on the campaign trail appear to conflate criminal conduct and unethical behavior. But the fact that he was not charged and convicted criminally by the IRS does not mean he was somehow exonerated from the House ethics charges.

The incident behind the charges

The issue that prompted the ethics investigation was whether Gingrich, the politician and history professor, engaged in tax fraud when he used tax-exempt organizations in the 1990s to finance the spread of his conservative political philosophy via distributed films of a college course he was teaching entitled “Renewing American Civilization.”

There is a long and well-established ban on using tax-exempt contributions to favor one side or the other in a political campaign. Gingrich insisted his college course was merely educational, and not campaign-oriented.

The Ethics Committee asked Gingrich about why he did not consult a tax lawyer before establishing the tax-exempt fundraising network around his project. He said he was simply teaching a college course. “It never occurred to me that this is an issue,” he told the committee.

The Ethics Committee considered whether to rule on the legal issue but ultimately declined to decide whether Gingrich violated tax laws, according to the committee report. Instead, it focused on his conduct with an eye toward enforcing House ethics rules.

“The subcommittee decided that regardless of the resolution of the … tax question, Mr. Gingrich’s conduct in this regard was improper, did not reflect creditably on the House, and was deserving of sanction,” the committee report says.

On Dec. 21, 1996, Gingrich admitted that he violated the House ethics rules and he apologized. He apologized not for breaking the law but for displaying poor judgment.

“With deep sadness, I agree. I did not seek legal counsel when I should have in order to ensure clear compliance with all applicable laws, and that was wrong,” Gingrich said. “Because I did not, I brought down on the people’s house a controversy which could weaken the faith people have in their government."

This admission and apology stands in stark contrast to more recent comments by the former speaker on the campaign trail.

The IRS findings

The Ethics Committee left it to the IRS to determine whether his alleged use of tax-exempt groups for political purposes was illegal.

The IRS subsequently upheld the tax-exempt status of two foundations linked to Gingrich and ruled that their support of the Gingrich course did not violate tax law. This is the basis for Gingrich’s claim of vindication and exoneration.

But in one of the cases, the IRS complained that the House Ethics Committee had refused to provide the agency with transcripts of confidential testimony given by foundation officials to the committee.

“It is possible that if the Ethics Committee had rendered full cooperation with our examination, the transcripts might have affected our conclusion,” the IRS said, acknowledging that it was a close case.