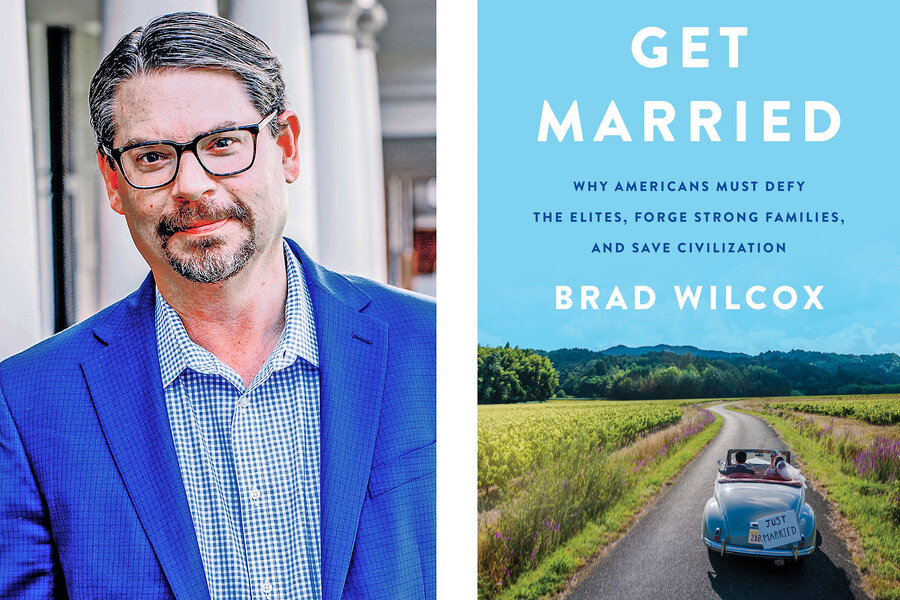

The case for getting and staying married, by author Brad Wilcox

Loading...

Brad Wilcox is the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia. A sociologist, he has studied how and why marriage has declined among adults in the United States and what the consequences are for family formation and for society.

In his book “Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Force Strong Families, and Save Civilization,” Mr. Wilcox laments what he describes as the “closing of the American heart” that is undermining marriage and family life. In 1960 some 72% of adults were married. Today that proportion is around 50%.

Why We Wrote This

Data suggests marriage can be a strong foundation for happiness and prosperity. Recent declines in marriage rates mirror similar declines in birthrates, a topic that the Monitor explored in a three-part series.

The first in the series looks at why U.S. parents are having fewer children. The second shows how immigrants are powering a population boom in rural Iowa. The third looks at the tumbling global birthrate and hard societal choices ahead.

“Get Married” details the social, economic, and cultural forces that shape how adolescents and adults view marriage. Mr. Wilcox also examines public policy options, from tax credits to vocational training and school choice, to promote and support marriage.

“Too many on the right have had a blind faith in the market’s power to bring prosperity and so much more to families,” he writes. From the left, the problem is a “blind faith in the state’s ability” to provide for families, a faith that undermines “the strength, stability, and solidarity of American family life.”

Mr. Wilcox spoke with the Monitor in a Q&A about his new book.

Brad Wilcox is the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia. A sociologist, he has studied how and why marriage has declined among adults in the United States and what the consequences are for family formation and for society. In his book “Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Force Strong Families, and Save Civilization,” Mr. Wilcox laments what he describes as the “closing of the American heart” that is undermining marriage and family life, including childbearing. In 1960, some 72% of adults were married. Today that proportion is around 50%.

“Get Married” details the social, economic, and cultural forces that shape how adolescents and adults view marriage. Mr. Wilcox also examines public policy options, from tax credits to vocational training and school choice, to promote and support marriage.

“Too many on the right have had a blind faith in the market’s power to bring prosperity and so much more to families,” he writes. From the left, the problem is a “blind faith in the state’s ability” to provide for families, a faith that undermines “the strength, stability, and solidarity of American family life.”

Why We Wrote This

Data suggests marriage can be a strong foundation for happiness and prosperity. Recent declines in marriage rates mirror similar declines in birthrates, a topic that the Monitor explored in a three-part series.

The first in the series looks at why U.S. parents are having fewer children. The second shows how immigrants are powering a population boom in rural Iowa. The third looks at the tumbling global birthrate and hard societal choices ahead.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What has happened to marriage and divorce rates in recent decades?

Since 1970, the marriage rate has fallen by more than 60%. For young adults, we’re projecting that 1 in 3 adults will never marry, heading into record demographic territory. About 1 in 2 adults currently are not married, and that’s also a record. When it comes to divorce, however, the news is better, in part because marriage has become more selective along educational, financial, and religious lines. We’re seeing that divorce has come down in America by about 40% since 1980. Many Americans think that 1 in 2 marriages ends in divorce today. But the data suggest for couples who are getting married recently, a majority of them are going to go the distance, and probably only about 40% will end up getting divorced.

How does the decline in U.S. marriages interact with declining fertility rates?

We see in the demographic research that one of the best predictors of having kids is being married and having a good relationship that makes you feel like you’re going to have a partner who is with you, and for you, in raising children. So the fact that fewer and fewer young adults are getting married, and the fact that more of them are postponing marriage, means that fewer young adults today are having children together, which is one big reason why our fertility rate is close to 1.7 [births per woman of childbearing age] right now.

What makes for an enduring marriage?

I argue in the book that there are markers of both happy and stable marriages. I specifically talk about the importance of fostering a sense of communion [the first C] in marriage. [Then there’s] cultivating an appreciation for how much your children depend upon you to have a good marriage, if you have kids. That’s the second C. The third C is commitment understood in terms of sexual fidelity and sort of seeing marriage as a lifelong enterprise. The fourth C is cash, recognizing the value of a steady stream of cash coming into the household and shared assets stabilizing marriage as well. And then the final C is community. We see the people who are surrounded by other couples and adults who have good marriages or a good approach to life are more likely to flourish in their marriages, versus couples who surround themselves with people who are not as favorably inclined to marriage and family are more likely to flounder in their marriages.

Your book shows that education has become a strong predictor of whether adults marry. Was it always this way?

When you look back in the ’60s and ’70s, there were not large educational, class, or racial differences in American marriage and family life. And, really, since the 1960s, we’ve seen growing gaps between Americans who are more and less educated, more and less affluent, and also growing gaps along racial lines as well. So marriage has become – and I think is a tragic development – more of the province of the well-educated and the affluent.

Your book subtitle refers to “defying the elites.” But the elites are the ones who are getting married and raising children together.

Right. I talk in the book about the way in which our elites talk left, and walk right, when it comes to marriage and family. What I mean by that is that, yes, our elites tend today to get married and stay married, and to honor and practice the virtues and values that are associated with marriage and strong families more generally. But when it comes to their positions of public authority and power, unfortunately, we often see our elites either denying the importance of marriage, or minimizing the importance of marriage in their roles as journalists, professors, school superintendents, Hollywood moguls, and C-suite executives.

Your argument that culture and media are promoting an anti-marriage agenda seems at odds with the fact that marriage, and the pursuit of marriage, is the oldest storyline of all.

You can certainly find examples in pop culture of stories and movies and TV shows and songs that paint a more rosy or honest portrait of marriage and family life, and I wouldn’t minimize that reality. But it’s important to acknowledge today that there are a lot of [news] stories that are painting a clearly false message about marriage. There was a story about women who are staying single getting richer in America on Bloomberg, and that is empirically false. There was an article in The New York Times [that claimed] married motherhood in America is a game no one wins. That’s just not understanding that there’s no group of women [that report being] more happy, on average, than married women aged 18 to 55.

You advocate a “success sequence” for young adults. Can you explain this?

The success sequence is this idea that there are three pillars to the American dream, financially, and those three pillars are education, work, and marriage. So the idea here is to teach young adults that if they get at least a high school degree, work full time in their 20s, and get married before having children, their odds of being poor are just 3%, [whereas] their odds of reaching the middle class or higher in their late 20s and 30s are 86%. It’s also a way to underline the value of these three institutions: education, work, and marriage. I think today that marriage piece is the most controversial step for critics of the sequence. But we’re also seeing a lot of young men not working full time. What my research indicates is that 1 in 4 adults in their prime who are not college educated are not working full time. That affects their marriage ability and also affects their marital stability.

What’s the evidence that such campaigns can change norms and behaviors in an individualistic society?

We’ve obviously had campaigns in the past on topics ranging from teen pregnancy to smoking to [tackling] COVID that had success in terms of moving the dial in terms of cultural sentiment and people’s behavior. I think we would be looking for someone or some institutions or an array of states and school districts and nonprofits to put out a success sequence-friendly message, particularly to adolescents and young adults.

Recent declines in marriage rates mirror similar declines in birthrates, a topic that the Monitor recently explored in a three-part series. The first looks at why U.S. parents are having fewer children. The second shows how immigrants are powering a population boom in rural Iowa. The third looks at the tumbling global birthrate and hard societal choices ahead.