‘We’re a resilient community’: After tragedy, Monterey Park seeks healing

Loading...

| Monterey Park, Calif.

In Monterey Park, people spoke of togetherness and resilience as the way to heal from the largest mass shooting this year.

That teamwork was evident at the city’s Langley Senior Center, where Sgt. Bing Han, who has been on the force for two decades, was called in on his day off. Normally, he would be visiting his parents and in-laws on this first day of the Lunar New Year. Instead, he’s helping at the facility, which has been turned into a trauma center to help victims’ families and anyone else needing counseling.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onMonterey Park, California, has overcome division and tragedy before, residents say. After Saturday’s mass shooting, they are resolved to rely on one another to do so again.

People are “stunned and shocked,” says Rep. Judy Chu, who has lived here for 37 years. At the same time, she says, “We’re a resilient community.”

Perhaps that comes from its history. In the mid-’70s, a local real estate developer advertised Monterey Park – just a 20-minute drive from Los Angeles’ Chinatown – as “the Chinese Beverly Hills.” In the decades that followed, the city became America’s “first suburban Chinatown.” It also became a cauldron of tension over English-first issues and discrimination.

Today, Sergeant Han describes Monterey Park as a “quiet” place, where “people feel safe walking their dog at nighttime.”

On the eve of Lunar New Year, FX was enjoying celebratory dumplings at the fellowship hall at Christ Lutheran Church in Monterey Park, where he sings in the choir.

The young man, who emigrated from China about 10 years ago, lives alone. The meal, attended by singles at the church, was a stand-in for the traditional meal that many Chinese, Vietnamese, and other families prepare to start their most important holiday of the year.

But that night, after more than 100,000 people thronged downtown Monterey Park at a happy street festival, celebration turned to tragedy – a mass shooting at a nearby ballroom dance studio that left 11 people dead and another nine wounded. FX, a computer worker who asked to be identified by his initials, was up all night. He lives just blocks from the incident, and a hovering helicopter kept him awake. So did his fears. The shooting was just so close. The suspect was still at large.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onMonterey Park, California, has overcome division and tragedy before, residents say. After Saturday’s mass shooting, they are resolved to rely on one another to do so again.

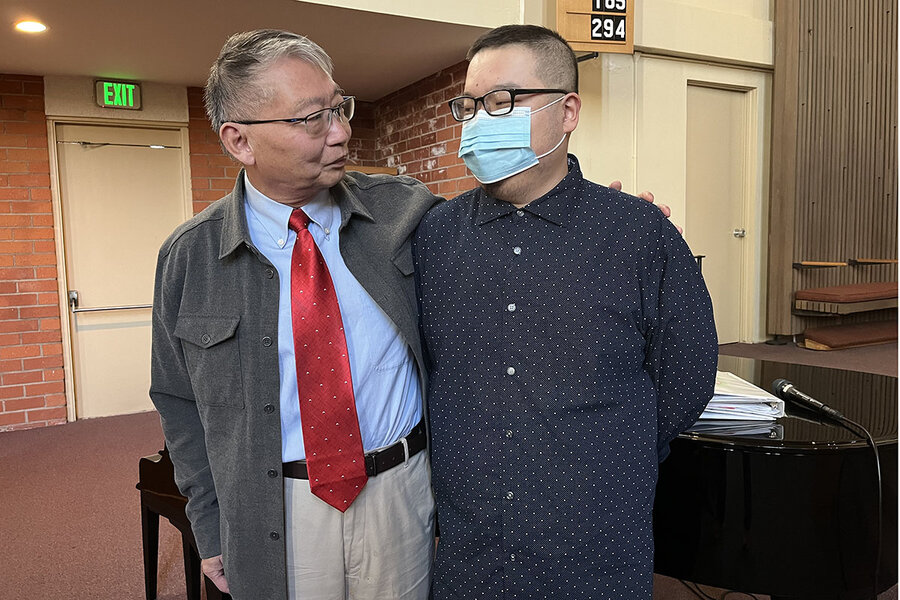

When he arrived at church for the English-language service the next morning, he was too anxious to sing. But a few members gathered around, hugging him and praying for him. “We told him: We can overcome this together. We know God’s love,” says John Fan, a longtime member of the church, where most congregants speak Chinese.

By mid-morning, the two men were practicing as a duo, accompanied by acoustic guitar and piano. At one point, Mr. Fan placed his arm around the shoulders of the young man. At the second service, FX was doing better and actually led the congregation in singing. “I’m still afraid,” he admits after the service. But he also feels the love of others: “Church is family.”

Over and over on that day after in Monterey Park, people spoke of togetherness and resilience as the way to heal from this tragedy – the largest mass shooting this year.

From early on, federal, county, and local law enforcement were coordinating. And one individual’s heroism prevented the tragedy from being even worse: At a second ballroom 2 miles from the mass shooting, the grandson of the ballroom’s founders sprang into action and wrestled a semiautomatic assault pistol away from the suspect, saving lives. By Sunday afternoon, police about 30 miles away surrounded the van of the suspect, Huu Can Tran, a 72-year-old man and former dance instructor, who then took his own life.

Less than 24 hours after the shooting, “we are able to say that justice has been done thanks to everyone working together,” said Mayor Henry Lo at a City Hall press conference.

That teamwork was evident at the city’s Langley Senior Center, where Sgt. Bing Han, who has been on the Monterey Park police force for two decades, was called in on his day off. Normally, he would be visiting his parents and in-laws on this first day of the Lunar New Year, honoring the elders. Instead, his wife and son went without him, he says from behind a strip of caution tape.

The facility has been turned into a trauma center to help victims’ families and anyone else needing counseling. On scene were members of the Los Angeles city crisis response team, the LA County Department of Mental Health, the FBI crisis team, the Red Cross, and volunteers. Sergeant Han describes Monterey Park as a “quiet” place, where “people feel safe walking their dog at nighttime.”

The tremendous response in this case reminds him of an earlier tragedy in August, when a rookie officer was murdered while off duty. Flowers and food flooded the Monterey Park police station. “The response from the community is pretty overwhelming.”

“We’re a resilient community”

Congresswoman Judy Chu has lived in Monterey Park for 37 years, including as a council member and mayor. Standing on the city’s main street of Garvey Avenue, just steps from the taped-off crime scene, she moves from media interview to media interview, emphasizing the city’s resilience and the need to work together to bring healing.

In an interview with the Monitor, she describes this city of 61,000 people as a diverse community (65% Asian), peaceful, and quiet, and a great place to raise kids and open a small business. Mini markets, restaurants, and other mom and pop shops line the street in a neighborhood of small single-family homes and garden apartments.

Living up to its name, a park lies within a half-mile of nearly every home. Indeed, on a huge expanse of brilliant green grass behind City Hall, a family is playing with their dog, and two women who emigrated from China four years ago are filming a video of their children. The kids are dressed in party clothes, reciting a poem about their homeland’s dynasties. These families weren’t going to let the tragedy stop them. “We are still celebrating because this is very important to Chinese people,” says Scarlett Shi, one of the mothers.

People are “stunned and shocked,” says Representative Chu, gesturing down the street to an area of empty vendor tents and a red banner welcoming the year of the rabbit. This was the first Lunar New Year festival since the pandemic and there was extra enthusiasm for it, she says. At the same time, “we’re a resilient community.”

Perhaps that comes from its history. In the mid-’70s, a local real estate developer advertised Monterey Park – just a 20-minute drive from LA’s Chinatown – as “the Chinese Beverly Hills.” In the three decades that followed, the city became a magnet for Taiwanese and then mainland Chinese, becoming America’s “first suburban Chinatown.” It also became a cauldron of tension over English-first issues, signs in Chinese, discrimination, and traffic.

Today, Chinese-language signs are everywhere, and the city is a destination point in a broad valley heavily populated by Asians and known for its fabulous restaurants. On Garfield Street in Alhambra, steps from the ballroom where the gunman was thwarted, Sam is waiting for a takeout order of eight for him and his friends. He drove all the way from LA’s Koreatown to come to Borneo Kalimantan Cuisine, which serves authentic food from Indonesia – his home country. The tragedy “is definitely unfortunate,” he says, but he doesn’t feel personally threatened. “It doesn’t only happen to Asians. It happens to everyone.”

Paying their respects

Christine Terrisse is waiting at the cross signal at Garvey Avenue, her preschool son holding her hand. In the other hand, she carries a bouquet of blue-dyed roses, cradled in baby’s breath.

After she crosses, the writer says that she is from Whittier, about 10 miles southeast from here. She’s looking to place the roses at a memorial, but doesn’t see anything – perhaps a nearby church will do. She is one of several nonresidents to come to the crime scene, pay their respects, and join in the mourning.

“I have friends in the Chinese-American community,” she explains, while minding her son. “I was getting kind of numb with all the shooting news and so I came here. I just felt I wanted to do something.”

A couple from Pacoima expresses similar sentiments. The violence also hits close to home. Imelda Nancilla recently heard that three young girls whom she knows were shot dead in her hometown in Mexico. They were to be buried Sunday. “My heart is broken,” she says. After the dance studio shooting, she told her husband, Fernando, that they had to come to Monterey Park to show respect for the people, the families.

Police are still searching for motive, though news reports say Mr. Tran gave informal lessons at the dance studio, met his ex-wife there, and had a hot temper. Before these details emerged, many in this community thought this might be a hate crime. That’s been a great concern in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, with Asian hate crimes up 339% in 2021 over 2020. It has motivated many to step up and watch out for each other.

Watching out for one another

Drew, a young man from nearby San Gabriel, another heavily Asian community near Monterey Park, came with his friend San to “check out the situation” and see if they could help.

The two are part of a grassroots group of volunteers that for two years has been patrolling LA’s Chinatown as a deterrent to violence. They walk the streets once a week, helping shop owners and trailing behind seniors to enhance their safety.

“I think the Asian community, it’s like very hesitant,” says Drew, as they walk past City Hall, the late afternoon sun casting long shadows. “But I feel like these are the times to actually do something.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Imelda Nancilla's last name.