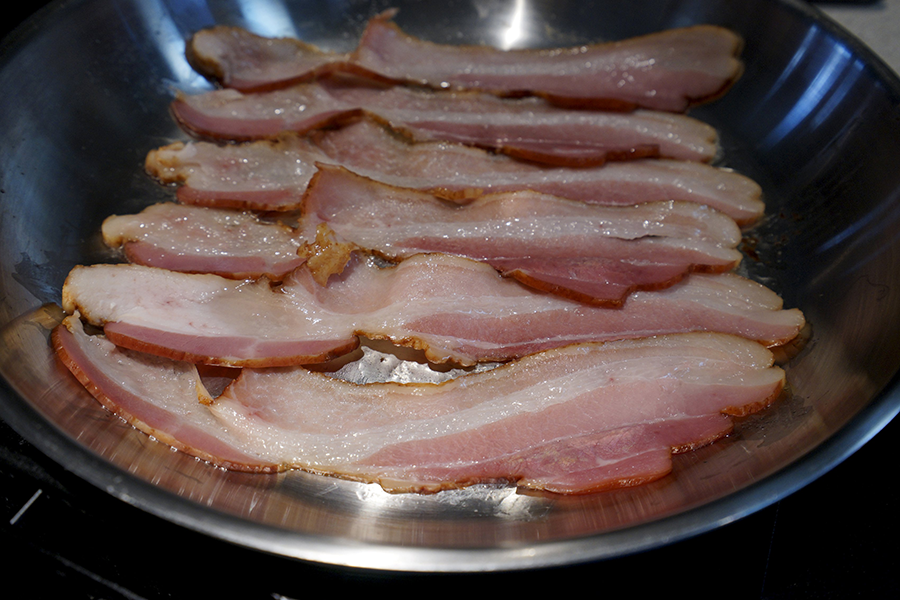

US bacon reserves plummet. What's behind the rise of the rasher?

Loading...

America’s future bacon supplies are running low.

Last week, the USDA reported that stocks of frozen pork bellies dropped from 53 million pounds at the end of 2015 to 18.5 million pounds at the end of 2016. NBC declared it “the first sign of the aporkalypse” as fears of an impending bacon shortage spread on social media.

But would-be Baconator eaters and bacon-scented deodorant users shouldn’t panic just yet. The drop in frozen pork belly stocks doesn’t necessarily signal trouble in the pork industry. But it is an interesting twist in the history of the humble rasher.

In past decades, the pork market "had a well-deserved reason for volatility," Steve Meyer, president of Paragon Economics, told Bloomberg in 2014. Demand for bacon would track the tomato harvest, spiking in late summer and early fall as Americans used it to top salads and bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwiches. It would then subside for the rest of the year as bacon returned to the breakfast table.

In 1961, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange introduced the frozen pork belly futures contract as a hedge against this seasonal volatility. Its prices tanked in the 1980s, explained Bloomberg’s David Sax, as low-fat diet fads turned Americans away from pork. The bellies were sold to the Soviet Union as cheap exports, or shipped to Africa as humanitarian aid.

Pig farmers’ fortunes changed in the early 1990s, when fast-food chains re-imagined bacon as a topping for burgers and sandwiches, sparking a surge in demand for the fatty strips. In 2013, Time reported that “bacon volume in food services grew by almost 25%. There was an annual growth rate of 2.4% from 2011 to 2013.”

The bacon craze meant that pork producers could count on strong demand year-round, and no longer had to keep warehouses full of pork bellies on hand. Demand fell, prompting the Chicago Mercantile Exchange to discontinue trade in the contracts in 2011. “With bacon accompanying salads, hamburgers, even chocolate, it is on call all year now, removing some of the demand for frozen bellies,” The New York Times reported at the time.

But with US pork consumption expected to grow in the coming decade, and exports to foreign markets like China also rising, hog farms have an incentive to boost production.

Last July, Reuters reported that construction of new US pork processing plants “could result in an extra 6 percent added to capacity by the end of 2017 compared with 2015 levels.” Dr. Meyer, whose research focuses on the pork industry, adds that “We've never had an expansion like this in my lifetime."

This means that plenty of pork bellies will be available for bacon in coming years; they’ll just spend less time in the meat locker. Rich Deaton, president of the Ohio Pork Council, doesn’t see reason for alarm. "Rest assured. The pork industry will not run out of supply. Ohio farmers will continue to work hard to ensure consumers receive the products they crave," he told NBC.