Japanese comic creators grapple with racism

Loading...

| Yokohama, Japan

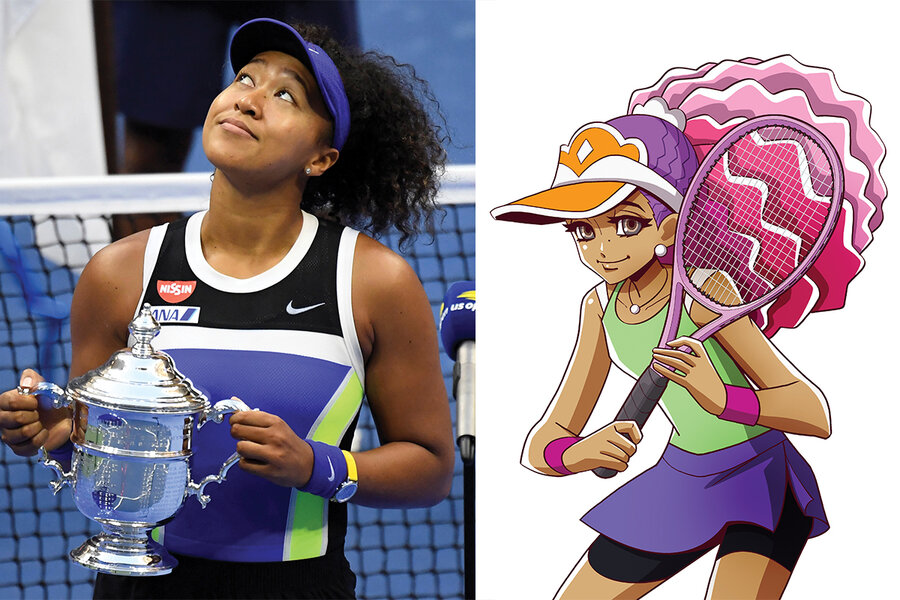

Japan’s tennis champion Naomi Osaka, who is biracial, was depicted in early cartoon representations with white skin and light-colored hair, causing an uproar from Japan to Australia. But now, with a new comic that celebrates her exploits – and better portrays her features – Ms. Osaka joins the crowded pantheon of strong female characters and a small but growing gallery of Black characters in Japanese manga.

Creators of manga, and its movie counterpart anime, have all too often relied on stereotypes in portraying the features of Black people.

Author and Japan Times columnist Baye McNeil points to the earlier debacle over Ms. Osaka’s cartoon image as a catalyst for change. “As awareness is raised in various Japanese media,” he says, “some artists are definitely taking better care when they choose to include non-Japanese characters in their works. Nobody wants to be the focus of negative global attention. It’s sad, but sometimes it takes an incident like this to make people take notice.”

Why We Wrote This

Japanese manga, or comics, influence global pop culture. By portraying Black characters with more respect and dignity, some manga artists are beginning to move beyond damaging stereotypes.

As a three-time Grand Slam champion and the world’s highest-paid female athlete, tennis player Naomi Osaka is a popular figure worldwide. In Japan, her image graces not only T-shirts and key holders, but now also the pages of manga – or comics.

Two previous attempts at illustrating Ms. Osaka, who is biracial – in an Australian newspaper cartoon and a Japanese advertisement – misfired when both portrayed her with white skin and light-colored hair.

But in December 2020, the magazine Nakayoshi debuted “Unrivaled NAOMI Tenkaichi” inspired by Ms. Osaka’s exploits (tenkaichi means “best of earth”). It avoids the earlier mistakes, in part because her sister, Mari, supervised the project. The tennis whiz – who was voted The Associated Press 2020 female athlete of the year in December – now joins manga’s crowded pantheon of strong female characters and a small but growing gallery of Black characters.

Why We Wrote This

Japanese manga, or comics, influence global pop culture. By portraying Black characters with more respect and dignity, some manga artists are beginning to move beyond damaging stereotypes.

It’s a sign of progress in a genre in which accurate depictions of racial diversity have been hard to come by. Japanese society is known for erasing or obscuring racial and ethnic differences. But experts suggest that a slow change is bringing a new look to some manga.

“More mangaka [creators of manga] are putting in the effort to portray Black characters more respectfully and appropriately,” says LaNeysha Campbell, a manga essayist who regularly contributes to the pop culture website “But Why Tho?” “A great example of this is Aran Ojiro, a supporting character in ‘Haikyū!!’ His features and skin tone are done in a way that respectfully captures and portrays Black features.”

Author and Japan Times columnist Baye McNeil points to the earlier debacle over Ms. Osaka’s cartoon image as a catalyst for change. “As awareness is raised in various Japanese media,” he says, “some artists are definitely taking better care when they choose to include non-Japanese characters in their works. Nobody wants to be the focus of negative global attention. It’s sad, but sometimes it takes an incident like this to make people take notice.”

Creators of manga, and its movie counterpart anime, have all too often relied on stereotypes in portraying the features of Black people.

“In many classic manga from the 1980s and ’90s, Black people are drawn with big lips and portrayed as intimidating, often stupid characters,” points out longtime manga fan Diamond Cheffin. “Even in the early 2000s, you still find those Black caricatures.”

Mr. McNeil ascribes manga artists’ attitude toward Black people to habit. “A lot of them are accustomed to drawing Black people in a certain way,” he says. “Though these characters are inaccurate, I don’t think they are necessarily intended to be offensive. It’s also true that those comics are not supposed to be consumed by non-Japanese.”

According to Ms. Campbell, until recently many Japanese manga artists have portrayed Black people in a less than flattering manner as a result of looking at Black culture through the lens of white American media.

“It is possible that the first impressions that Japanese audiences had of Black people were formed through these racist and stereotypical portrayals,” she says. “And while it has been well over 70 years since those depictions, they still contribute to the negative attitudes towards Black people and their offensive and problematic portrayals in manga.”

Some manga characters testify to the artists’ love for Black culture. Many Japanese authors grew up consuming American comics, music, and movies, and strive to include those icons in their work as a sort of homage. But that can still lead to mischaracterization. One example is the character named Coffee in the popular TV show and subsequent manga series “Cowboy Bebop.”

“Coffee is a typical blaxploitation character,” says film and TV critic Kambole Campbell. “She is basically Foxy Brown, but on Mars.” The 1974 movie “Foxy Brown,” which starred Pam Grier as the hypersexualized protagonist, was criticized in the United States for its portrayal of Black people, particularly Black women.

“Cowboy Bebop” director Shinichirō Watanabe took a different approach with the 2019 anime series “Carole & Tuesday,” whose co-protagonist is an overalls-wearing Black girl with dreadlocks and a bright smile.

Ms. Osaka, who has a Haitian father and a Japanese mother, has said she has experienced racism in Japan in the past. “Japan is a very homogenous country, so tackling racism has been challenging for me,” she wrote in a piece in July 2020 for Esquire. “I have received racist comments online and even on TV. But that’s the minority. In reality, biracial people – especially biracial athletes – ... have been embraced by the majority of the public, fans, sponsors, and media. We can’t let the ignorance of a few hold back the progressiveness of the masses.”

“Unrivaled NAOMI Tenkaichi,” the new manga about Ms. Osaka, is written with a different perspective in mind, and with an appeal to one of the groups that embraces the genre: teen girls.

“We want to convey her charm,” write the story’s authors, Jitsuna and Kizuna Kamikita, a twin-sister team that signs their work as Futago Kamikita, in an email. “Not to mention her greatness as a tennis player. Naomi is a person full of humanity. We also like her ideas and her willingness to act on them. At the same time, she has a sense of humor that softens her seriousness.” They add, “We also think it’s essential to draw a warm story about the family who raised her.”

The choice of Ms. Osaka was a natural one for Nakayoshi, says the publication’s editor. “Self-reliant heroines and cool girls are very popular with our readers,” says Izumi Zushi.

In the comic, Ms. Osaka’s character plays “space tennis,” “traveling across the universe with her parents and sister to meet new challenges and protect everyone’s dreams and hopes from the ‘Darkness,’” Ms. Zushi says.

Nakayoshi is one of the many publications targeting female readers, and the Kamikita twins are part of a massive female contingent. In the West, many people think that otaku, or nerd culture, is mainly a guy thing, but women – both as creators and consumers – represent a sizable part of the community.

According to the Japan Magazine Publishers Association, in 2019 there were at least 23 magazines in the shojo (aimed at teenage girls) and josei (aimed at older readers) manga categories with a total monthly circulation of more than 1.5 million copies.

Aside from the manga about Ms. Osaka, recent developments in the industry point to a new sensibility toward ethnic distinctions. “I do find that portrayal of Black people has come a long way,” the fan, Ms. Cheffin, says. “We are getting cool characters like Ogun from ‘Fire Force.’ Overall, this new generation is doing an awesome job. However, I’d like to see more Black characters on a greater scale, not just sprinkled here and there.”

As artists become more aware of the global reach of manga, says Mr. McNeil, “the more they will learn to create stories and characters that take into consideration the diverse sensibilities of their growing readership.”