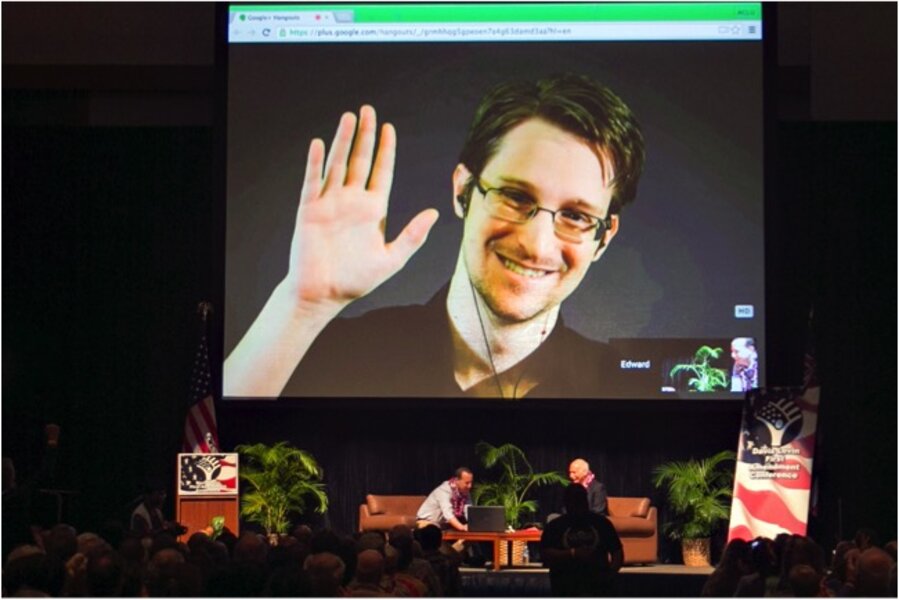

California's new digital privacy act: The Snowden effect?

Loading...

Digital privacy is ramping up, as California passes a law to prevent the government from collecting the kind of en masse private data revealed in Edward Snowden's data leak.

California became the fourth US state with law of this type when Gov. Jerry Brown signed it into effect Thursday.

The law includes anything stored in an email, digital document, or text message, as well as location information, the LA Times reported. The bill's sponsors chose these types of communications based on the high-volume data requests that Verizon, Twitter, and AT&T received in 2014.

Privacy watchdogs hail the bill, known as CalECPA, as a victory for the Fourth Amendment in the digital world.

"It will require that law enforcement get a warrant before poking around in our digital records," wrote the California-based advocacy group Consumer Watchdog. "If the cops want to search your desk for letters and files, they need a warrant. But who relies on paper files and letters these days?"

The group described the federal Electronic Communications Act as "outdated" because it allows the government to collect location and call information from phones, as well as view emails that have been stored on a server for more than 180 days.

Many have pointed to the impact of Edward Snowden's revelations on international law, including the recent Safe Harbor judicial decision that complicated data-sharing across the Atlantic, as the Economist writes:

As the trickle of data crossing the Atlantic built into a tsunami, worries in Europe grew. But it took leaks by Edward Snowden, a contractor for America’s National Security Agency (NSA), showing widespread snooping to nudge the commission into a serious attempt at renegotiation.

Edward Snowden pointed several to legislative and judicial actions sparked by his risky reveal of US government surveillance, in June op-ed in the New York Times.

"Ending the mass surveillance of private phone calls under the Patriot Act is a historic victory for the rights of every citizen," he wrote. "This is the power of an informed public."

California is only the latest example of a state taking action to protect its citizens' privacy. Utah, Texas and Maine each have a privacy law like the one California just passed. Utah's law passed almost unanimously in March 2014 and prevents data collected without a warrant from being used in a criminal case, even if the federal government collected it.

The laws in Maine and Texas, passed in 2013, require the government to get a warrant to search digital data like the new California law, the Electronic Freedom Foundation said in a release.

With states as politically diverse as California, Utah, Texas, and Maine "taking affirmative steps to bring search warrant requirements to sensitive electronic data, Congress should see that privacy legislation is bipartisan and feasible," wrote EFF's Hanni Fakhoury. "Will Congress follow?"