How Google helps people seek refuge from Colorado floods

Loading...

When Nick St. George needed to give his girlfriend directions from South Dakota back home to Denver last Saturday, he relied on Google Maps. But with the northern route into Denver riddled with massive flooding, road closures, and power outages, Mr. St. George turned to Google for an extra reason: safety. Using the Google Crisis Map and COtrip.org, he was able to guide her through treacherous conditions created by more than 30 inches of rain, plus ensure her home in Longmont, Colo., was out of harms way.

"It was definitely a source of great relief in a time of uncertainty," he says.

Coloradans in crisis have turned to Google Maps, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), social media, and other digital tools to find resources and map routes, often successfully reaching their destination (and knowing whether that destination is in a flood zone). But as with any natural disaster, a flood moves faster than the Internet. This has left some residents piecing together what information they can as the technology catches up.

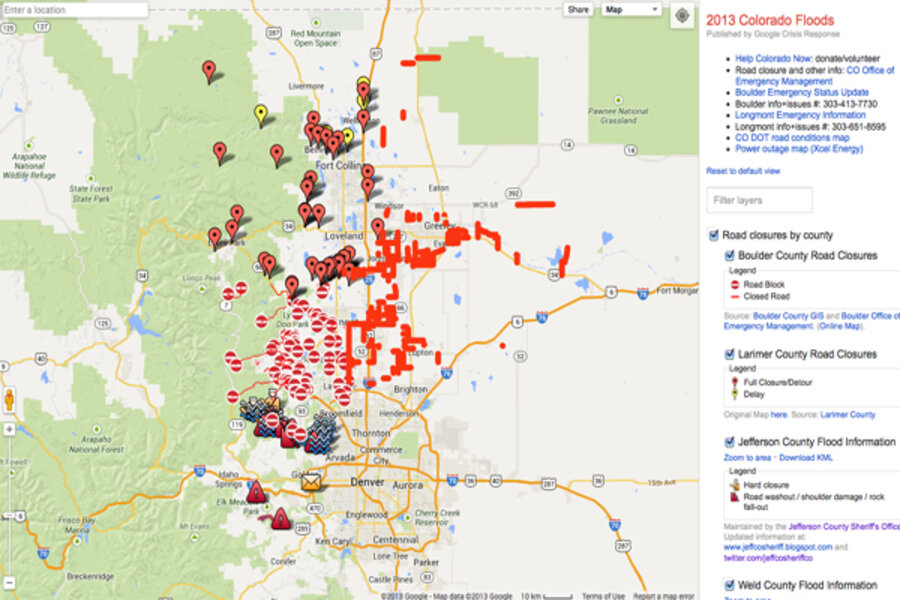

The Google Crisis Response Team set up a Google Crisis Map of the floods on Sept. 12, one day after the bulk of the rain started. The map, which automatically zooms in to the areas hardest hit by the floods (viewers can zoom in and out), includes pinpoints where streets are closed, thick red lines over inaccessible roads, hazard signs where there are road blocks, and red triangles to show rock fall outs or shoulder damage, among other symbols that vary from county to county. Map viewers can click each point to find out more information, and can check boxes so the map only shows alerts in certain areas or includes photos and webcam imagery.

“A lot of problems during disasters are typically information problems," says Nigel Snoad, product manager at Google Crisis Response. "People are increasingly turning to the Internet during this time.”

Google Crisis Maps attempts to solve the information problem by bringing together public information from a variety of local, state, and regional sources, working with local organizations to increase information flow and calling up sources to double-check information is correct. Crisis Maps were first officially started in 2011 with the earthquake and tsunami in Japan (though Google had worked on crisis map products before that).

While local websites map out similar information, Google's team benefits from having the full force and know-how of the company behind it. Its database system can handle huge influxes of traffic that would crash other sites. In addition, Google has experts in many fields and in many areas around the world. Take, for example, Ryan Falor, formerly a product manager at Google Crisis Response and now works with Google Groups in Boulder, Colo. He says that the site is updated around the clock by a rotating group of several Google employees.

Mr. Falor adds that Google Crisis Response can't map every disaster, but when the group feels that its resources can be of help, it steps in.

"A big determinant is whether we can actually make a difference," he says.

For some Coloradans, it has even become a repeat resource. Michael St. James, a music executive who lives in Denver, first used the Crisis Map to track the wildfires that burned through parts of western Colorado last year. So when a friend needed navigation help during the flooding, he knew where to go.

“In Longmont, a friend with extra rooms in his house [had] put the word out to the residents who were evacuated, but providing directions for them to find a safe place was nearly impossible,” Mr. St. James says. “With the crisis map, we were able to plot a course to get them there safely. That night he hosted four people and pets.”

St. James also points out that the Google Crisis Map includes rural areas that don't get much media attention. Plus, the map is more compatible with mobile devices. Mobile sites from newspapers and TV stations, he says, often jumble important facts with advertisements and side stories.

“What people need is actionable, updated, uncluttered information delivered immediately in a crisis,” he says.

Google isn’t the only website using tech to get the word out. FEMA has an ongoing online photo directory showing what it looks like on the ground. Weld County (north of Denver) is updating a road closure map on its website. The Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department (west of Denver) created their own Google Map that showed specific information in their county, and were tweeting updates with the hashtag #JeffCoFlood.

And people are logging on. As of Sept. 17, the Jefferson County map had more than 1 million views.

However, when a natural disaster strikes, information isn’t always updated with accuracy or speed.

Lori Jarrett, who owns her own real estate company and lives in Kersey, Colo. with her daughter, tweeted the link to the Google Crisis Map on Sept. 14 as a resource to her friends and real estate clients. Two days later, however, she said it wasn’t what she hoped.

“The map is not accurate when I look at it, though it looks like they are starting to update it a bit,” she says. She points to highways she had tried to cross that were flooded, bridges that had been washed out, and the disparity of resources marked in more populated areas, such as Boulder, as opposed to those near her small town. The map has filled in over time, but wasn't complete when Ms. Jarrett needed it. Kersey, a town of about 1,500, is located near the South Platte River, which was rising at 100 times the normal rate on Friday. Weld County, where the town is located, estimates the floods have caused more than $230 million in damage. Falor says that, in areas that are being hit hard, it can be tough to stay on top of new developments.

“It’s a tricky business," he says. "What we try to do is be sure we are referencing the most official, most accurate sources possible."

Especially at times when the situation changes hour by hour, the emergency responders that provide Google with its information may not be able to stay on top of updating their website.

“We can't be everywhere but we want to make sure we have the tools so people can map their own community," Mr. Snoad says.