Tastes like chicken? ‘Cultured meat’ arrives on menus.

Loading...

Consumers may soon find meat on restaurant menus that has never walked the earth – grown from cell to fillet.

The product, called “cultured” or “cultivated” meat, is reaching more plates. Cultivated chicken has been sold in a Singapore restaurant since 2020, and in June the Department of Agriculture approved the sale of cultured chicken in the United States by two companies. More than 150 businesses worldwide are working to put beef, fish, and pork on the market, too.

Why We Wrote This

“Cultured chicken” is now available for sale in some U.S. restaurants. Supporters tout its environmental benefits, yet critics raise concerns over cost and practicality.

Supporters hope the food will prove more environmentally friendly and protect animal rights, yet concerns linger over costs and feasibility. Some call the product, which tastes, smells, and looks like chicken, real meat, but that raises philosophical questions about what meat is.

“This is the kind of thing that gets moral philosophers like myself excited,” says Josh May, a professor of philosophy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Some people are concerned that maybe [cultured meat] is unnatural,” he says, “but it doesn’t seem any less natural than factory-farmed meat.”

Consumers may soon find meat on restaurant menus that has never walked the earth – grown from cell to fillet.

The product, called “cultured” or “cultivated” meat, is reaching more plates. Cultivated chicken has been sold in a Singapore restaurant since 2020, and in June the Department of Agriculture approved the sale of cultured chicken in the United States by two companies. More than 150 businesses worldwide are working to put beef, fish, and pork on the market, too.

Supporters hope the food will prove more environmentally friendly and protect animal rights, yet concerns linger over costs and feasibility.

Why We Wrote This

“Cultured chicken” is now available for sale in some U.S. restaurants. Supporters tout its environmental benefits, yet critics raise concerns over cost and practicality.

What is cultured meat?

It’s not genetically modified or a plant-based alternative. Some would call this product that tastes, smells, and looks like chicken, real meat, but that raises philosophical questions about what “meat” is.

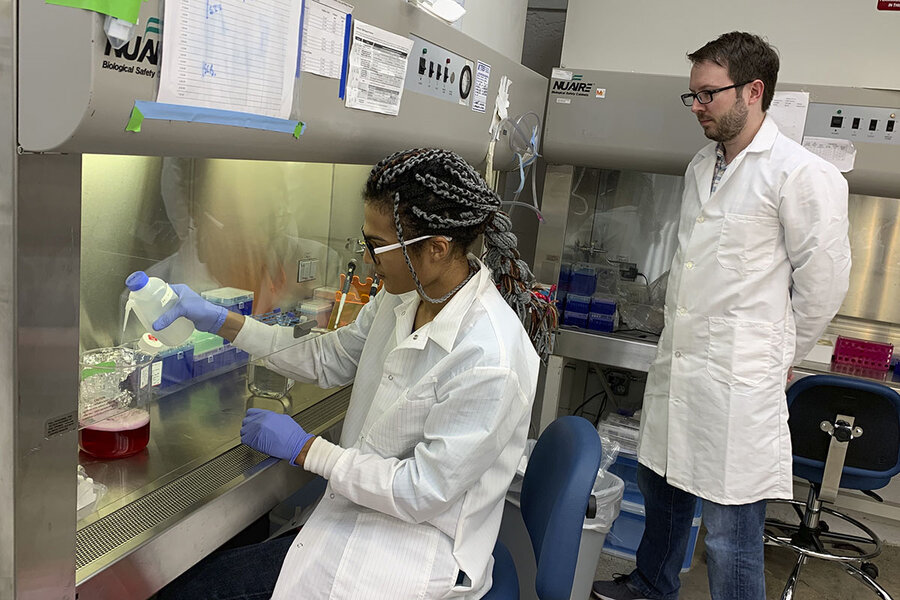

Cultured meat begins as a cell from an egg or a piece of traditionally butchered meat. The cells are fed amino acids, vitamins, and other nutrients in a bioreactor. Two to three weeks later, the meat is processed into forms that consumers are familiar with, such as a nugget.

“I think sometimes people have this idea in their head that the meat they’re eating is grown in a petri dish. That’s not the case,” says Josh Tetrick, CEO of Good Meat, one of the two USDA-approved cultured chicken manufacturers in the U.S. Initial research is in a lab, but the meat is made in a production facility, he says.

Is cultured meat healthy?

Both Good Meat and Upside Foods, the other cultured meat company with USDA approval, say that the nutritional profiles of their products are almost identical to conventional meats.

Upside Foods has made public its own nutrient analysis, evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration, which found “somewhat higher levels” of folate and cholesterol and slightly different mineral and metal content than conventional meat. The levels were within the range of those found in other common foods, the report said. Good Meat discloses a few nutritional facts and says on its website that its product is “high in B vitamins.”

Many potential customers seem grossed out by the product, though. A study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology last year found that 35% of meat eaters and 55% of vegetarians were “too disgusted” by cultured meat to try it.

Shoppers won’t find cultured chicken on the shelves of grocery stores in the U.S. yet. Instead, the product will first appear in upscale restaurants in San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

What is the impact on animals and the planet?

By eliminating the rearing and slaughter of animals, cultured meat companies say their product helps reduce animal cruelty.

“This is the kind of thing that gets moral philosophers like myself excited,” says Josh May, a professor of philosophy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Some people are concerned that maybe [cultured meat] is unnatural,” he says, “but it doesn’t seem any less natural than factory-farmed meat.”

Large-scale meat production has become highly mechanized and profit-driven. The idyllic image of a farmer in overalls tending to humanely treated, well-grazed animals is more a myth than reality. Factory-farmed meat makes up about 99% of the U.S. meat market, according to estimates by animal rights groups.

Cultured meat companies also claim that their product will be better for the environment. Their process uses far less land because there’s no need to house animals or grow their feed. Cultured beef, especially, could reduce the number of cattle on farms – a significant source of methane emissions.

But there is little expert consensus on cultured meat’s environmental impact. Some research has found that producing cultured meat emits fewer greenhouse gases than farmed meat, but other studies contradicted this. Cultured meat may also require greater energy usage than conventional production. Much of the environmental impact will depend on whether the energy used is renewable and on the efficiency of future production technology.

Some voices are calling for slowing down. More than 60 French scientists and learned society members signed an open letter in February cautioning against cultured meat’s sale before further scientific research is available.

Can companies make enough meat?

Currently, creators of cultivated meat are limited to making tens of thousands of pounds per year, due to their production capabilities. Large-scale production of hundreds of millions of pounds of meat per year is at least two years off, says Mr. Tetrick of Good Meat.

Above sheer output, industry leaders want to reach price parity with conventional meat. Neither Good Meat nor Upside Foods has disclosed the price of its product. “Our production costs are still quite high ... and we are not making a profit on anything we sell to restaurants,” a Good Meat spokesperson said in an email. “That will change as we tackle some of the remaining technical and engineering hurdles inherent in large-scale commercial production.”

Proponents claim prices have been falling fast. In 2013, the first cultured meat burger reportedly cost $330,000. More recent estimates range from $11 per pound to just under $29 per pound. This would be before grocery stores and restaurants hike up the price, however.

Critics are skeptical that cultured meat companies will be able to fulfill their ambitious goals. Businesses face extreme obstacles in everything from cell metabolism and ingredient costs to facility construction and bioreactor design.

Could “lab meat” succeed even if it’s expensive?

Given a growing consumer consciousness around animal rights and climate change, supporters foresee a future meat market where consumers will choose between different kinds of conventional meat, cultured meat, and plant-based alternatives. People with the financial resources may choose to buy cultured meat or meat from humanely raised animals while lower-cost options remain.

Consumers may reevaluate their dining choices if general meat prices rise due to climate changes, says Dr. May of the University of Alabama. “We can’t keep doing what we’re doing, which is expecting that once you’re a wealthy nation, you eat meat with almost every meal. ... It’s not necessary.”

Several conventional meat companies have invested in cultured meat. Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. invests in Good Meat, and Tyson Foods and Cargill invest in Upside Foods. No conventional meat companies responded to requests for comment.

Approved sale of cultivated chicken in the U.S. is a landmark moment, but not yet a revolution. While cultured meat’s widespread consumption and impact on the economy seem a step closer to reality, scientists, philosophers, and the product’s own manufacturers acknowledge years of work lie ahead.