Drones in space: Can a helicopter take flight on Mars?

Loading...

NASA has done it again. This afternoon, the agency stuck a landing on Mars for the 6th time.

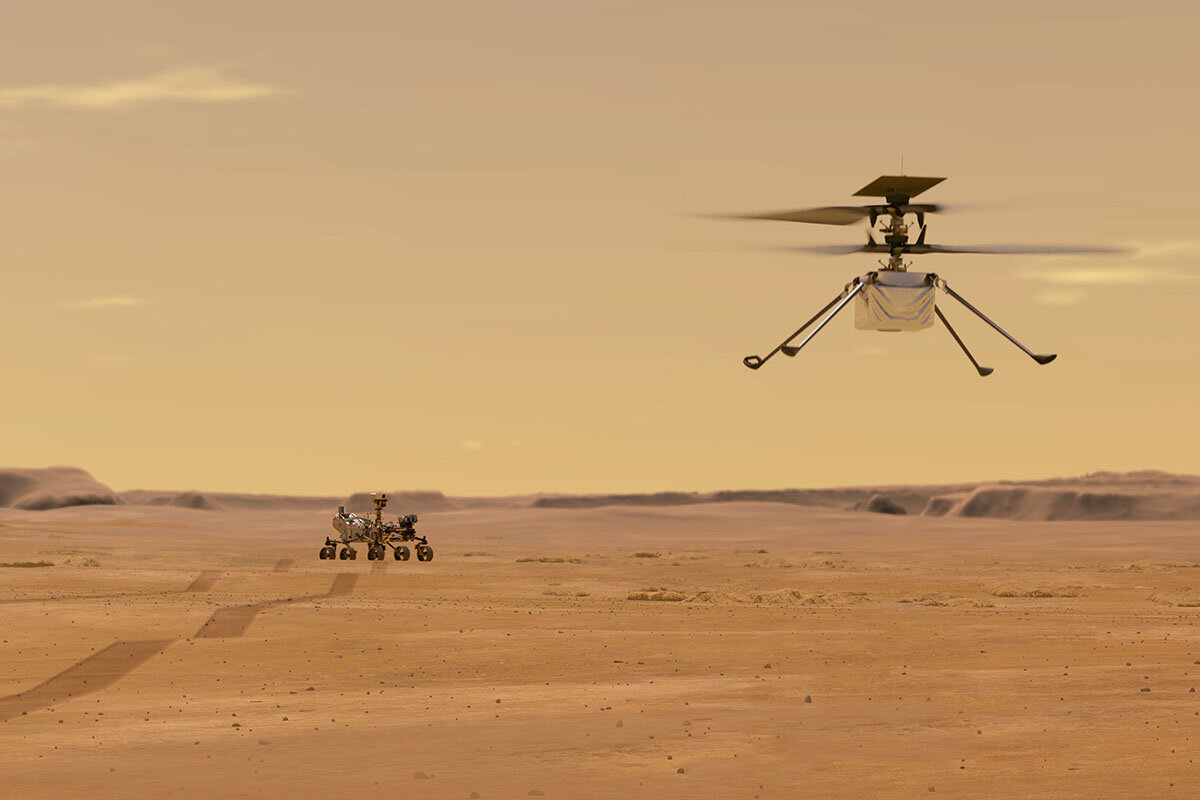

The latest Martian rover, Perseverance, did not arrive alone. A hitchhiker came along for the journey, strapped to the belly of the rover. Named Ingenuity, the tiny helicopter is experimental technology, and weighs just 4 pounds. Beginning this spring, it will attempt to take to the Martian skies, marking the first powered flight of any craft on another planet.

Why We Wrote This

The quest to explore beyond our home planet tests humanity’s know-how, but also kindles hope and teaches lessons back on Earth. With today’s Mars landing, a rover called Perseverance and a helicopter called Ingenuity exemplify this spirit.

Successful test flights could mean that helicopters will become an important part of the suite of tools sent to explore the red planet going forward. They would add a bird's-eye view to our understanding of Mars, and could serve as a scout for rovers – or even humans, one day.

“Science isn’t always at an easy landing site. It isn’t always an easy terrain,” says Doug Adams, an aerospace systems engineer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory who is not working on Ingenuity. “And helicopters, or rotorcraft, give you that flexibility to take your platform to the science and to observe where you might want to go to collect the science.”

It’s getting busy on Mars.

Today, NASA successfully landed its 6th probe on the surface of our neighboring planet, and earlier this month both the United Arab Emirates and China also had spacecraft arrive in orbit to study Mars. Altogether, nearly 50 spacecraft have been sent to explore Mars over the past half century.

NASA’s Perseverance rover could fundamentally change how we see the red planet and our place in the universe over the course of its mission, as it seeks out signs of past life. But it is not alone. A hitchhiker came along for the journey that could also make history in its own right.

Why We Wrote This

The quest to explore beyond our home planet tests humanity’s know-how, but also kindles hope and teaches lessons back on Earth. With today’s Mars landing, a rover called Perseverance and a helicopter called Ingenuity exemplify this spirit.

Strapped to the belly of the Perseverance rover is a tiny, lightweight helicopter. Named Ingenuity, the flying envoy is experimental technology. Beginning this spring, it will attempt to take to the Martian skies, marking the first powered flight of any craft on another planet.

If the test flights are successful – or even if they’re not – Ingenuity could open up tantalizing new possibilities for how we explore the red planet and other parts of the solar system in the future.

“Science isn’t always at an easy landing site. It isn’t always an easy terrain,” says Doug Adams, an aerospace systems engineer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory who is not working on Ingenuity. “Science doesn’t come to you. You have to go to the science. And helicopters, or rotorcraft, give you that flexibility to take your platform to the science and to observe where you might want to go to collect the science.”

A feat of a flight

To the annoyance of some and delight of others, similar technology flies all over tourist destinations on Earth: drones. So it might seem like a simple feat to send a tiny helicopter to Mars, too.

But there are a few key differences between Mars and the Earth.

Mars has an atmosphere that is about 1% the volume of Earth’s. That means that anything on Mars experiences significantly less pressure than on Earth. The gravity on Mars is also roughly a third of that on Earth.

The Ingenuity team has honed the helicopter’s design here on Earth, doing their best to simulate the Martian environment in special pressurized chambers. To combat the gravity issue, they added a tether to the top of the helicopter to reduce its weight.

To mitigate these differences, Ingenuity was built from very light materials, but with longer, stiffer rotors that spin faster than they would need to on Earth. The space helicopter weighs 4 pounds, sits about 19 inches tall, and its rotor system spans about 4 feet.

“We feel pretty confident that we can fly,” says Tim Canham, senior software engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the operations lead for Ingenuity. But there could be surprises on Mars that weren’t in the simulated environments.

To figure out how to get around, Ingenuity can’t just pull up Waze or GoogleMaps on Mars, either. And not just because we don’t have road maps for the red planet ... yet. GPS relies on a network of satellites in orbit around our planet, which doesn’t exist on Mars. Furthermore, Mars has a weak and irregular magnetic field. On Earth, compasses rely on the planet’s strong magnetic field to orient themselves.

Instead, Ingenuity will use an optical navigation system. Essentially, the craft will snap pictures of its surroundings as it flies to detect and identify features on the planet. It will rely on those images to orient itself and figure out how to get where it’s programmed to go.

A further hurdle for the helicopter is something that all spacecraft on Mars struggle with: power. While a rover can rest in the sunshine to charge its batteries on solar power if it needs to, a helicopter requires more and constant power to keep its body airborne. It’s a balancing act with weight.

Ingenuity will rely on solar power, as other options are prohibitively heavy. It will operate autonomously, but use the Perseverance rover to relay data and receive commands from mission control back on Earth.

The helicopter will perform five tests, if all goes well. The first three will test its basic flight and navigation capabilities, and the final two will push it to its limits to see where they may lie for space helicopter development.

A future filled with space helicopters

NASA has been billing this as a Wright Brothers moment. Indeed, powered flight on another world would be historic.

But Erik Conway, historian at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says that the first Mars rover – Sojourner in 1997 – might be a better analogy.

Sojourner was also a technological test. It only traveled about 330 feet from the Pathfinder lander that it accompanied, but it opened the door for the many rovers that have come since and revolutionized our view of Mars.

Mr. Canham agrees that Ingenuity is a “baby step” toward following the same development path of the rovers. “Nobody’s ever flown a rotorcraft outside Earth’s atmosphere, much less on Mars,” he says.

Other NASA engineers will be watching closely as Ingenuity begins spinning its rotors through Martian air. Johns Hopkins’ Dr. Adams is one of them. He is spacecraft systems engineer for NASA’s Dragonfly mission to Titan, a moon of Saturn. Dragonfly, which is currently in development for a projected 2027 launch, will be a rotorcraft lander mission to study the conditions under which life might have first emerged.

Titan and Mars bear some similarities – namely weak magnetic fields – but there are also differences. Titan, for instance, has a much denser atmosphere than Mars. Dragonfly will also need to be much more massive than Ingenuity to carry all the scientific tools needed, as the Titan probe will not be a technological test. Still, Dr. Adams says the success (or even failure) of an autonomous helicopter on another world will help Dragonfly.

“We will learn something from Ingenuity’s experience, regardless of what that is,” he says. “And, you know, the best case scenario is very good. And even in the worst case scenario, we benefit.”

On Mars, successful test flights could mean that helicopters will become an important part of the suite of exploration tools. They would add a bird's-eye view to our understanding of the planet, and could serve as a scout for rovers – or even humans, one day. They could scope out the landscape much more quickly than a rover and determine whether it was navigable terrain, or even worth exploring.

And perhaps space helicopter technology, like rovers before it, will enable us to discover something that changes the way we see our universe.

“We’ve learned a great deal in my lifetime about the solar system,” Dr. Conway says. “What I was taught from textbooks in the ’70s is turning out not to quite be right.”

“When we first were able to send spacecraft to Mars, there was this image of Mars as potentially habited. And that gets blown up by a mission [about 50 years ago],” he explains, referring to NASA’s Mariner 4, the first mission to successfully fly by Mars. Since then, we’ve learned that Mars is neither as dynamic as we first surmised nor as static as early missions led us to believe. And there is still much to discover about our neighboring planet.