The final chapter: Cassini probe completes first daring dive between Saturn and its rings

Loading...

In the early hours of Thursday morning, NASA's Cassini space probe re-established contact with Earth after a risky dive between Saturn and its rings and began to transmit data collected during the maneuver back to the space agency. The probe's communication dish had been purposely directed to orient itself away from Earth to act as a protective shield against any particulates the probe might have encountered during the dive, which could have damaged the spacecraft prematurely.

The successful completion of the maneuver on Wednesday is the latest in a long string of historic firsts for the probe. But the completion of the dive was also a bittersweet moment marking the initiation of the final phase of Cassini's almost 20-year space odyssey.

Cassini was launched in October 1997 to explore Saturn and its moons, reaching Saturn's orbit in July 2004. But after so many years of research and data collection, Cassini is finally starting to show its age; and with fuel running low, the probe will conduct a series of final close passes to the solar system's second-largest gas giant, before finally plunging into the atmosphere of the very planet that it has orbited for the past 12 years.

"NASA and the Cassini team's devotion to the mission are an example for all of us," Harold C. Connolly Jr., chair of the department of geology at Rowan University in New Jersey, tells The Christian Science Monitor in an email. "I remember as a child living in southern New Jersey being glued to the TV when the Voyager images came back to Earth, and now I am an upper manager of a NASA space mission – I hope Cassini-Huygens has [similarly] motivated a new generation of future scientists and explorers."

Dr. Connolly is currently working on the OSIRIS-REx program, NASA's first mission to collect an asteroid sample and return it to Earth for analysis. He tells the Monitor that Cassini – along with its companion lander, Huygens, which landed on Saturn's moon Titan, in 2005 – have revolutionized scientific understanding of the gas giants and its system of moons. But that only scratches the surface of the achievements the Cassini probe represents.

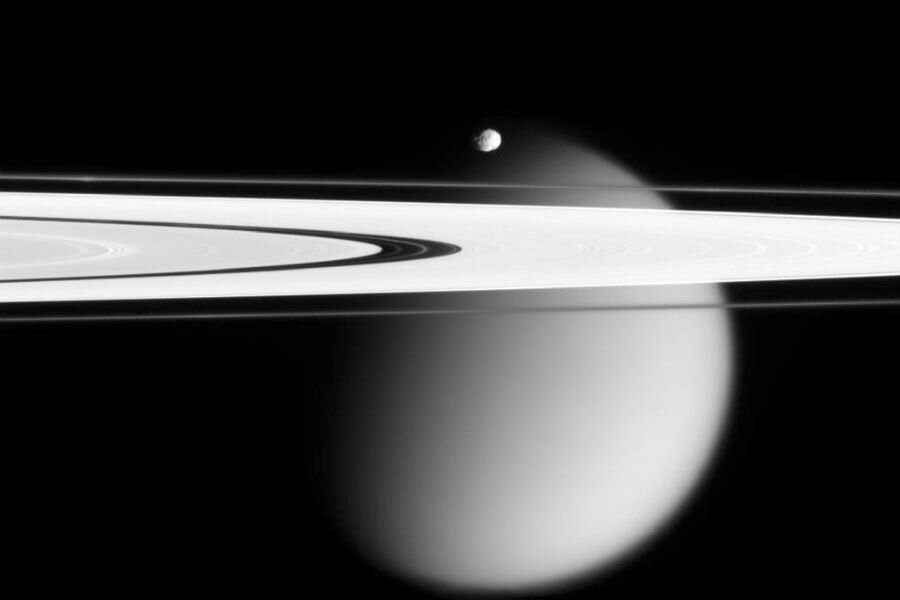

"Cassini has provided a better understanding of Saturn's ring system, why it exists, the weather conditions on Saturn, and the mysteries of its largest moon, Titan: A truly primitive world potentially similar to what Earth was like in the earliest days of its life," Connolly adds. "From an engineering point, we as humans have learned how to navigate and fly around the massive planet of Saturn, which provides key information on how to fly to and around other planets. We have also learned the extent of the lifetime of various payload instruments, those critical to meet science objectives and those needed for navigation."

The latest dive is one of the most difficult challenges the probe has ever faced – but it won't be the last. Cassini's final stage, referred to as the "Grand Finale" by NASA, entails a series of weekly dives – 22 in total – into the 1,500-mile gap between Saturn and its rings. During these plunges, Cassini will be able to create precise maps of Saturn's gravity and magnetic fields in order to deduce the planet's internal arrangement, sample ring particles in Saturn's atmosphere, and take unprecedentedly close pictures of the gas giant's clouds.

"No spacecraft has ever been this close to Saturn before," said Cassini project manager Earl Maize in a NASA statement. "We could only rely on predictions, based on our experience with Saturn's other rings, of what we thought this gap between the rings and Saturn would be like."

Now that the Grand Finale is underway, all that is left to do is process information from Cassini as it arrives before the probe plunges into Saturn. But why destroy the superstar probe at all?

"[The main] reason for this ending to the Cassini mission is something that NASA is very worried about – contamination of our life forms on planets and moons that may harbor other forms of life," says Nicholas Suntzeff, a professor of Observational Astronomy at Texas A&M University, tells the Monitor via email. "The moons of Saturn – Enceladus and Titan – could have life or complex organic molecules that are the soup out of which life forms."

As it makes its final dive on Sept. 15, he explains, Cassini will burn up in the gas giant's thick atmosphere. This will eliminate the risk of the probe eventually accidentally crashing into the moons once the spacecraft's fuel is used up, which could potentially seed these moons with biological material or microbial life forms from Earth to what could be delicate alien ecosystems.

But despite the destructive nature of the final plunge, it will be a fitting end to an illustrious career, says Connolly.

"[Because of probes like Cassini,] we have learned what we can do, as humans, in the realm of exploration ... to shed light into the mysteries of the Solar System and process the new information into knowledge," he adds.