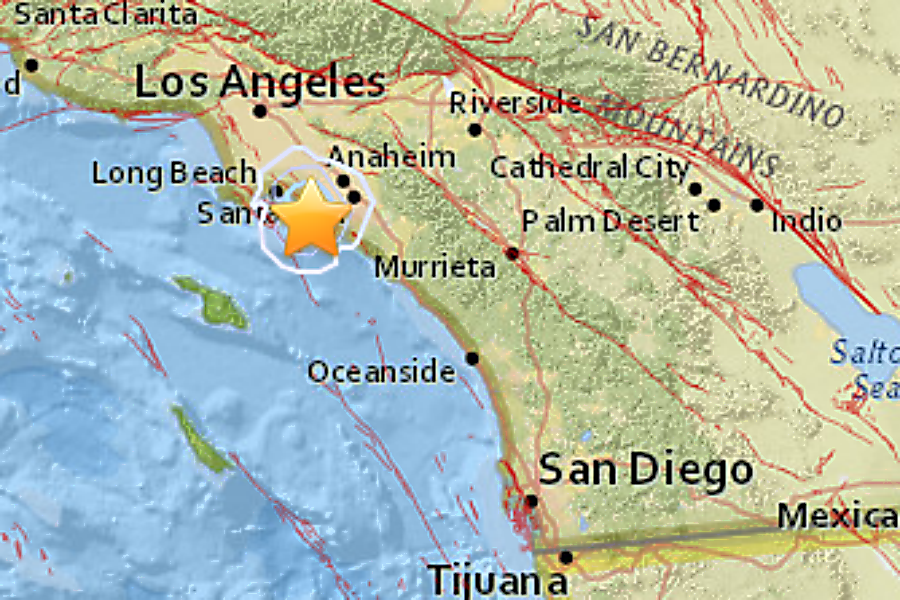

Huntington Beach rattled by magnitude 3.1 earthquake

Loading...

A magnitude 3.1 earthquake rattled residents south of Los Angeles early Monday morning.

The quake, center three miles west south west of Huntington Beach, Calif., struck at 3:49 a.m. Pacific time at a depth of 8.7 miles, the US Geological Survey reported.

No injuries or serious damage was reported.

Residents in Garden Grove, Santa Ana, Anaheim, Seal Beach, Costa Mesa, Westminster, Fountain Valley, Buena Park, Cypress, Long Beach and Cerritos reported feeling the temblor, ABC News reports.

The USGS tracks the seismic stress that builds up along the California fault lines.

The constant plate tectonic motions between the Pacific and North American plates guarantees that the crust in the western US is continually building up stress. The image of crustal velocities provided by extensive GPS coverage reveals where these velocities change rapidly over short distances, demanding that the intervening crustal rock stretch and build up stress over time. Such a map of the stress reveals two main lines where stress is concentrated: The San Andreas fault zone and the Eastern California Shear Zone. These zones have experienced numerous earthquakes over the century and a half that earthquakes have been historically observed.

The mechanism of stress buildup within these fault zones is uncertain. One hypothesis is that the hot rocks below the upper 15-km-thick layer (the upper crust that has the vast majority of continental earthquakes) flows continually in response to periodic earthquakes, forcing the upper crust to bend with this flow. Another hypothesis is that slip of the deeper continuation of faults, steady slip that doesn’t produce earthquakes but still involves motions across the fault, forces the upper crust around the faults to bend and thus concentrate stress. Both hypotheses are the subject of active research. But the fact remains that high stressing rates observed on the surface likely translate to high stressing rates at the depths (~10 km) where earthquakes typically nucleate, so these stressing rates are a guide to the seismic hazard.

Southern California has a long history of earthquakes.

The first strong earthquake listed in earthquake annals for California occurred in the Los Angeles region in 1769. Four violent shocks were recorded by the Gaspar de Portola Expedition, in camp about 30 miles southeast of Los Angeles center. Most authorities speculate, even though the record is very incomplete, that this was a major earthquake....

The Long Beach earthquake of March 1933 eliminated all doubts regarding the need for earthquake resistant design for structures in California. Forty million dollars property damage resulted; 115 lives were lost. The major damage occurred in the thickly settled district from Long Beach to the industrial section south of Los Angeles, where unfavorable geological conditions (made land, water-soaked alluvium) combined with much poor structural work to increase the damage. At Long Beach, buildings collapsed, tanks fell through roofs, and houses displaced on foundations. School buildings were among those structures most generally and severely damaged. The epicenter was offshore, southeast of Long Beach, on the Newport - Inglewood Fault. Magnitude 6.3.