Scientists win Nobel for bizarre neutrino discovery

Loading...

| Stockholm/London

A Japanese and a Canadian scientist won the 2015 Nobel Prize for Physics on Tuesday for discovering that elusive subatomic particles called neutrinos have mass, opening a new window onto the fundamental nature of the universe.

Neutrinos are the second most bountiful particles after photons, which carry light, with trillions of them streaming through our bodies every second, but their true nature has been poorly understood.

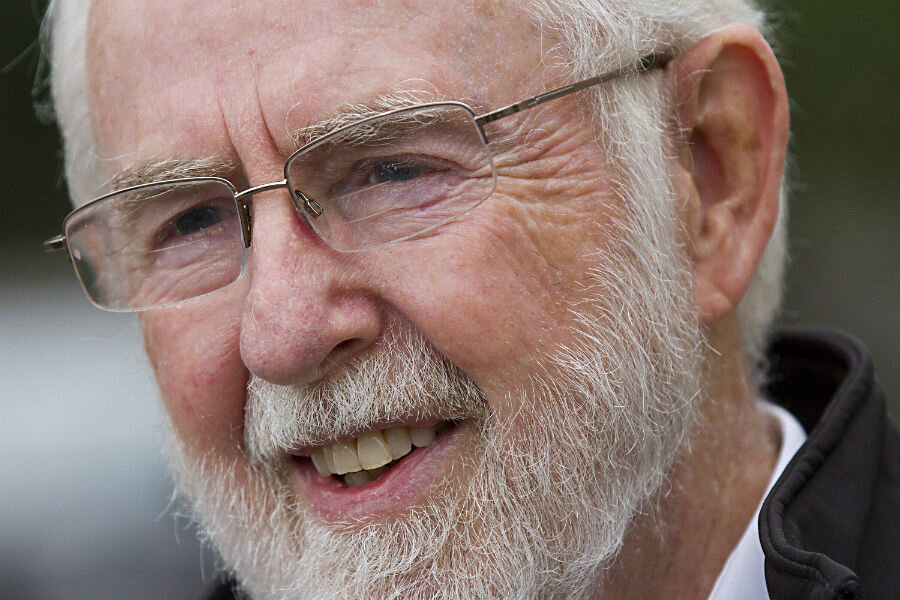

Takaaki Kajita and Arthur McDonald's breakthrough was the discovery of a phenomenon called neutrino oscillation that has upended scientific thinking and promises to change understanding about the history and future fate of the cosmos.

"It is a discovery that will change the books in physics, so it is really major discovery," Barbro Asman, a Nobel committee member and professor of physics at Stockholm University, told Reuters.

In awarding the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said the finding had "changed our understanding of the innermost workings of matter and can prove crucial to our view of the universe."

For many years, the central enigma with neutrinos was that up to two-thirds fewer of them were detected on Earth than expected, based on how many should be flooding through the cosmos from our Sun and other stars or left over from the Big Bang.

Around the turn of the millennium, Kajita and McDonald, using different experiments, managed to explain this by showing that neutrinos actually changed identities, or "flavors," and therefore must have some mass, however small.

McDonald told a news conference in Stockholm by telephone that this not only gave scientists a more complete understanding of the world at a fundamental level but could also shed light on the science behind fusion power, which causes stars to shine and could one day be tapped as a source of electricity on Earth.

"Yes, there certainly was a Eureka moment in this experiment when we were able to see thatneutrinos appeared to change from one type to the other in traveling from the Sun to the Earth," he said.

New physics

McDonald is professor emeritus at Queen's University in Canada, while Kajita is director of the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research at the University of Tokyo.

"When I took the phone call and heard that they'd decided on the prize, it was a huge honor. I'm still so shocked I don't really know what to say," a grinning Kajita told a packed news conference in Tokyo.

Kajita said his work was important because it showed there must be a new kind of physics beyond the so-called Standard Model of fundamental particles, which requires neutrinos to be massless.

The final piece of the Standard Model was slotted into place in 2012, with the detection of the Higgs boson particle at CERN's Large Hadron Collider outside Geneva. But it is now clear that the model does not provide a complete picture of how the fundamental constituents of the universe function.

While McDonald and Kajita have cracked a key part of the puzzle, other questions remain, including the exact masses of neutrinos and whether different types exist beyond the electron-neutrinos, muon-neutrinos and tau-neutrinos identified so far.

Michael Turner, director of the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics at the University of Chicago, who knows both laureates, said, "neutrinos attract a special kind of person."

Unlike scientists who work on high-energy particle physics in massive particle accelerators that produce trillions of events, neutrino scientists search for elusive particles with detectors deep in the ground, away from interference from cosmic and other radiation.

The 8 million Swedish crown ($962,000) physics prize is the second of this year's Nobels. Previous winners of the physics prize have included Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr and Marie Curie.

The prizes were first awarded in 1901 to honor achievements in science, literature and peace in accordance with the will of dynamite inventor and business tycoon Alfred Nobel.

The prize for medicine was awarded on Monday to three scientists for their work in developing drugs to fight parasitic diseases including malaria and elephantiasis. ($1 = 8.3151 Swedish crowns)

(Additional reporting by Sven Nordenstam, Elaine Lies and Julie Steenhuysen; Editing by Alistair Scrutton and Alison Williams)